Over at “the other place” I’ve been in conversation with Richard Wright about divine action, and one of his points, all too common in the science-faith discussion, is that science has increasingly shown nature to operate through natural causes (and hence the accusations of invoking the “God of the Gaps” in any consideration of design). So divine action is to be sought (at least in Richard’s rather more positive view, compared to some others) in answered prayer, biblical miracles and so on, but not in nature.

What those who make such arguments are always blind to is that it is their prior metaphysical commitments, and nothing in the scientific data itself, which conjure into being the God of the Gaps by dividing nature into the entirely arbitrary categories of “natural” and “supernatural” and then apportioning phenomena between them.

Archaeologist James Hoffmeier puts this well in relation to the phenomena of the Bible, which are what I want to discuss here. He is commenting on liberal theologian Langdon Gilkey’s 1960s criticism of the then-popular discipline of biblical archaeology (a criticism I heard repeated recently by William G Dever):

Langdon Gilkey… critiqued Wright and others for using orthodox language to describe God’s action in history but then attributing natural causes to the events. Gilkey’s critique actually reflects an Enlightenment-based scientific worldview that bifurcates natural and supernatural, which is antithetical to ancient worldviews in which no such dichotomy existed.

A recent example to which to apply this is the identification by Steve Collins of Tell el-Hammam with biblical Sodom, which I covered here. He adduces various evidences in the dig for an exploding astromical body, such as a comet, to account for the destruction levels found in the whole vicinity, thereby lending credence to the historical aspects of the Genesis account of Sodom’s overthrow.

A Gilkey or a Dever would reply that if you’re going to invoke a divine miracle, you should not need a comet. Such critics would say that the scientifically ignorant biblical writer simply attributed supernatural agency to a natural event, and indeed the “minimalist” archaeologist Israel Finkelstein has already suggested that the Genesis episode is an aetiological tale to account for the disaster retrospectively. These criticisms imply that ancient writers were so overwhelmed by unusual events that they had to invoke divinity to make sense of their world when it departed from the normal (ie “natural”) course.

A Gilkey or a Dever would reply that if you’re going to invoke a divine miracle, you should not need a comet. Such critics would say that the scientifically ignorant biblical writer simply attributed supernatural agency to a natural event, and indeed the “minimalist” archaeologist Israel Finkelstein has already suggested that the Genesis episode is an aetiological tale to account for the disaster retrospectively. These criticisms imply that ancient writers were so overwhelmed by unusual events that they had to invoke divinity to make sense of their world when it departed from the normal (ie “natural”) course.

Two hundred years of skeptical biblical criticism has rejected the historicity of the Bible on just these grounds. The Scriptures are full of miraculous events, fulfilled prophecies, divine communications and so on, which just don’t happen in real life. Therefore they are fictional (or, more subtly, a special form of literature containing spiritual truth but not factual truth – a thoroughly liberal idea belatedly imported like a Trojan horse into the Evangelical mindset by those like Kenton Sparks and Peter Enns).

But there also is an “orthodox” Evangelical counterpart to this unnatural separation of natural and supernatural in the Bible. A while ago I mentioned Kenneth Kitchen’s pointing out numerous instances in recorded history of the Jordan being blocked by landslips at just the site where the waters “piled up in a heap” in the book of Joshua, enabling Israel to cross dryshod. A Fundamentalist commenter disdainfully rejected this as simply indicating Kitchen’s unbelief in miracles. Once again, the Bible is seen as a special case – the instances of such a damming down through recorded history are all “natural”, but the one recorded in Exodus must be different, because the Bible is a book about God, not nature.

Between those two theological extremes is the more common, and subtle, position of the average believer, for whom the world of the Bible is somehow unconsciously cordoned off from the world in which they themselves live, in which most things are natural (barring some personal experiences of the divine, in many cases). The Bible world, however, is one in which God speaks to people in dreams, sends angels, and interferes with nature to bless or judge. Moreover, Bible characters seem to be aware that they’re important actors in a play called “Salvation History”, rather than living real lives.

A king like Nebuchadnezzar in Daniel has a swirly moustache and is thoroughly evil like a pantomime villain, rather than being a real complex individual as one sees, say, Richard Nixon to have been when he sought spiritual advice from Billy Graham. (I realised  this dramatically when, in a recent Bible Study, a friend who usually plays the villain in village pantomimes inadvertantly slipped into role when reading Nebuchadnezzar’s acount of his dream!) Since such Bible characters are nearly always imagined as wearing generic tea-towel garb (regardless of whether they are Noah in 3rd millennium BC Mesopotamia or Peter in 1st century AD Judaea!) I have dubbed this view of the scriptual world “The Flannelgraph Bible”.

this dramatically when, in a recent Bible Study, a friend who usually plays the villain in village pantomimes inadvertantly slipped into role when reading Nebuchadnezzar’s acount of his dream!) Since such Bible characters are nearly always imagined as wearing generic tea-towel garb (regardless of whether they are Noah in 3rd millennium BC Mesopotamia or Peter in 1st century AD Judaea!) I have dubbed this view of the scriptual world “The Flannelgraph Bible”.

But we have the understanding entirely wrong. The Bible’s writers (and its historical characters) had no interest whatsoever in pitting the world of God against the world of nature, because neither for them, nor for anyone else in the world at that time, was there even a thing called “nature”. Rather, the “USP” of the Bible was that it was about the world of Yahweh against the world of the false gods of the nations. In every other way, it was very similar to the world that surrounded it. To quote another archaeologist, John M Monson:

The key lesson here is that in the light of parallel accounts from the ancient Near East there is little justification for dismissing the biblical conquest episodes on account of the miracles, deity, and hyperbole incorporated in the text. These are recognizable and unexceptional features of Near Eastern texts ancient and modern.

Now, there are events attributed to God in the Bible that would be unusual or miraculous in any context. The aforementioned destruction of the cities of the plain is one example. And of course the resurrection of the Lord is supremely so. But many of the features that have led either to rejection of trust in the Bible’s historicity, or to its being promoted into a quasi-mythical realm divorced from its context by believers, are simply the effect of the Bible characters’ living in the world such as we have it, but having a worldview that assumed that God is active in all things. It changes the world.

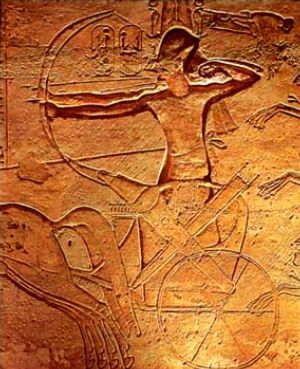

Kings of the pagan ANE attributed their military victories to their patron deities. They were guided by prophets, and when such a word (or perhaps a divine omen) led to such a victory, they dutifully recorded that Amun, or Marduk, had commanded them to win the victory.

Kings of the pagan ANE attributed their military victories to their patron deities. They were guided by prophets, and when such a word (or perhaps a divine omen) led to such a victory, they dutifully recorded that Amun, or Marduk, had commanded them to win the victory.

Vivid dreams, especially those of leaders, were always of spiritual significance. Nowadays, although in Thailand and throughout the Far East dreams are considered often to come through spirits or the Holy Spirit, we tend to discount any significance to ours – even of the kind commended by our recent seer Sigmund Freud, now considered a false prophet.

If ancient kings suffered a defeat or a famine, the anger of their god was the cause. If a providential occurrence gave them victory, then as a matter of course it was attributed to the gods. All this is familiar from the Bible books, and is typical of the ANE literature whose historicity is never seriously doubted.

The disturbing thing for many of us is that this realisation makes us fear that the Bible world – that is, the world of Yahweh – is no different from that of those of Chemosh, or Dagon, or Molech, or Horus, or Baal. If all those gods were false, and yet somehow mediated prophecy, omens, dreams and wondrous deliverances, then what grounds do we have for believing in the God of the Bible?

The thing to remember, though, is that the Bible was written, and the faith of Israel and ultimately the Church was forged, over millennia in just such a pluralistic world – and decisively not in our historically aberrant one, in which the burning question is whether there is such a thing as the supernatural at all, or whether instead everything happens from “material efficient causes”. Truly, the man spoke wisely when he said that it’s not a question of whether you believe in God, but of what kind of God you believe in.

According to the Old Testament Israel’s religion was intended from the start to bring glory to Yahweh amongst the nations, essentially by defeating their gods in one way or another. One plank of this was the sheer scale of the deliverances that brought Israel into being – that is, the astonishing feat of coming out from under the nose of the most powerful nation of the world, having “bugged Pharaoh with real bugs” and thrown “the horse and its rider into the sea”, maintained the nation for forty years in the wilderness, and displaced “seven nations greater and more numerous”.

Another plank was to be the wisdom of this nation of rebellious ex-slaves evidenced in their God-given torah and, indeed, in the persuasiveness of their radically monotheistic theology itself.

Another plank was to be the wisdom of this nation of rebellious ex-slaves evidenced in their God-given torah and, indeed, in the persuasiveness of their radically monotheistic theology itself.

Much later, of course, it was in the culmination of numerous prophecies in the life, teaching, atoning death and resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and in the vindication of these by his accurate prophecy of the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple 40 years in the future. (This last was in close accordance, moreover, with what the prophet Daniel had foretold). It’s in these kind of areas that we look for the distinctiveness of the God of Israel, and not in the bare fact of the Bible’s supernaturalism.

And what justification do we have for believing in that distinctiveness? Well, I know a good number of Jews who demonstrate the truth of the Passover not only by celebrating it, but by their very existence, and by the continued relevance of their torah. Of course, as a Christian I know many more who testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, the Messiah of the New Covenant promised by the Hebrew prophets as the culmintation of the promise to Abraham. And of course, a vast majority of the monotheists in the world not in those two categories claim to worship the God of Abraham in a faith clearly derived from the Bible. Nearly four billion people evidence that all gods are not the same.

The various pantheons of Mesopotamia, the Levant, Egypt, Greece, Rome or the northern tribes – even the attempted monotheisms like that of Aten by Akhnaten – are all only to be found now in museums and works of fantasy. History has not yet ended, but it has followed a persistent trend.

Yahweh claimed to be the true and living God, and appears to be the only one left standing of those competing with him in biblical days. In his name many even experience dreams, miraculous deliverances and prophetic words in the ordinary world, just as they did in the Bible (rather than in the Flannelgraph Bible where it is the ordinary that is excluded). The Bible really is about the real world of experience.

But what of those other books? I mean, the books in which things only happen through “natural causes” that operate magically on their own, and in which the God of Israel either keeps his distance or doesn’t even exist, and so is not mentioned as the active power behind the world? Well, at some stage in life we all have to put away the Flannelgraph, like other childish things.