Continuing my attempts to place the early chapters of Genesis within some historical context, I noticed for the first time this week that Genesis doesn’t mention any foreign gods at all in its fifty chapters. That seems remarkable to me, for I’ve never heard mention of it before, though it must undoubtedly have been noticed by someone over the last three thousand years. I look to the scholars to explain it.

But considering the book spans time from “the beginning” to, perhaps, 1600BC, and involves characters who are active in Mesopotamia, Canaan and Egypt, and that it mentions tribal origins over all the then-known world, you’d expect the gods of the nations at least to receive a mention or two, and they don’t.

There are a couple of possible exceptions, according to a survey I’ve just done. One is Jacob’s telling his people to put away their “foreign gods” before going up to Yahweh at Bethel – but the word is the untypical nekar, “foreigner”, and I suppose it might even be an indication only to take the bloodline, not foreign employees. if not, Jacob seems very easygoing about syncretism in his family group.

Another mention is Rachel’s purloining of Laban’s teraphim, often translated “household gods”, but Laban actually gets a prophetic word in a dream from Yahweh before setting off in pursuit, and the issue seems more about the theft than any devotion to other deities. In fact, teraphim (meaning “healers”) occur with a mixture of acceptance and criticism throughout Scripture even into post-exilic times. For example, King David has some, which are used to save his life, though his devotion to Yahweh is never in doubt even in that passage. At other times they are linked with idolatry. There are scholars who argue that the Mesopotamian equivalent (often very much like those prehistoric “Venus” figurines one sees) may be simply health charms or reminders of revered ancestors, so teraphim may not be “gods” as such at all.

Another mention is Rachel’s purloining of Laban’s teraphim, often translated “household gods”, but Laban actually gets a prophetic word in a dream from Yahweh before setting off in pursuit, and the issue seems more about the theft than any devotion to other deities. In fact, teraphim (meaning “healers”) occur with a mixture of acceptance and criticism throughout Scripture even into post-exilic times. For example, King David has some, which are used to save his life, though his devotion to Yahweh is never in doubt even in that passage. At other times they are linked with idolatry. There are scholars who argue that the Mesopotamian equivalent (often very much like those prehistoric “Venus” figurines one sees) may be simply health charms or reminders of revered ancestors, so teraphim may not be “gods” as such at all.

The only other thing I could find was that Joseph’s Egyptian wife was the daughter of a “priest of On”, but for all the insight into his religion that gives he might as well have been Russian Orthodox. Oh yes, and I should mention that there are some names with roots derived from pagan deities, such as “Abimelech”. But as for the gods themselves, they’re not named – even as something generic like “the gods” – nor are they apparently consulted by anyone. In fact, there is a pattern in Genesis of foreigners responding positively to words or judgements from the patriarchs’ God.

As I hinted, I have absolutely no explanation for this, for the false gods of Egypt and the nations are prominent in Exodus and the rest of the OT. But my reason for mentioning it is that the absence of the gods makes the absence of people, other than Adam and his offspring, in Gen. 2-11, less unique and surprising than it might otherwise seem. As some scholars have suggested, the narrative is exclusively focused on the line of Adam for one good reason – that he is regarded as the forbear (and forerunner) of Israel, for whom Genesis was written.

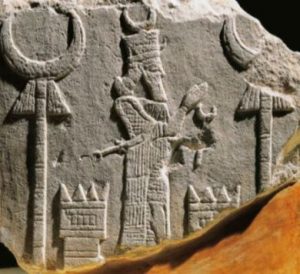

We know that many deities were worshipped in the Mesopotamia of Abraham and his ancestors, in the various regions of the Levant in which his family wandered, and of course in Egypt where they ended up for 400 years. And likewise, in the period of history after the Flood, and probably before if it is the same Flood as that of the cuneiform texts, we know there were whole nations of people worshipping them, rather than Yahweh (who is unknown, it seems, from that period from outside sources). Yet Genesis 2-11 deals only with those who worship Yahweh. The most likely reason, then, is not that only these people existed in the world, but that the writer was as uninterested in the others for his literary purpose as he was in their pantheons.

So while I’m here, let me recount a few hints in the text that the writer of Genesis was fully aware that other humans existed.

- Eden is a land or region (as is Nod, to which Cain later flees). This implies some kind of geopolitical entity. So, of course, do names like “Havilah”, Asshur” and “Cush” in ch2. It could be argued that they denote lands at the time of writing, not the time of the events – but that, of course, puts many YECs in a cleft stick, as they believe the flood entirely changed the world’s geography, so there would be no point in relating post-flood nations to regions at the time of Eden; and anyway such regions would indicate there were pre-flood national populations beyond Adam’s clan.

- Cain and Abel follow agriculture and herding respectively – complete overkill for a population consisting of them and two parents alone, but perfectly sensible in a bigger culture.

- Cain’s wife is the famous example of evidence for an external population. More telling is the risk he faces from “whoever finds him” in his wanderings away from his family, and the fact that he builds a city named after his son Enoch (“Enoch” being etymologically the name of a king). A city for a family is called a “house”!

- After naming Cain’s descendants, the writer returns to Adam’s third son Seth, and his son Enosh. But then he adds the strange comment that “at that time men began to call on the name of Yahweh”. Which men would those be? In Genesis, the phrase “calling on the name of the Lord” seems usually to imply sacrificing to him as Abraham did. But Adam knew Yahweh, and we know that both Cain and Abel sacrified to him. It’s hard to believe that Seth or his family didn’t, and even if they began later in life, they wouldn’t be the first to do so. The verse, then, appears to suggest that some outsiders began to worship Yahweh either under his covenant name, or at least in substance.

- For all that Gen 2-11 is a story of increasing evil, which might well include the perversion of religion into paganism (as in Romans 1), the line of Seth is full of reminders that this family, at least to an extent, remembered their familial relationship to the God of Adam.

- Enoch (in the seventh recorded generation from Adam) “walked with God, and he was no more, because God took him away”.

- Noah’s father Lamech hoped that his new son would help mitigate the curse placed on the ground by Yahweh in Adam’s time, implying a continuity of faith. Noah, of course, knew the Lord, and attested that he was also the God of Shem.

- Laban who worships Yahweh, albeit perhaps syncretistically, calls on “the God of Abraham and the God of Nahor, the God of their father [ie Terah]” in an oath. It’s true that Josh 24.2 says that their ancestors including Terah, father of Abraham and Nahor, lived beyond the River and worshipped other gods, but that may indicate partial apostasy (all too common even in Israel), or even just that they lived in pagan surroundings, a sense it seems to have when the prophets tell Israel they will be exiled and “worship gods they have not known.”

- The “sons of God and daughters of men” episode in Gen 6 is mysterious. I know three common explanations – that the “son of God” were fallen angels and the offspring demons: that they were Adam’s line marrying Cain’s: or that they were kings introducing the sin of polygamy. Despite its ancient origin in 2nd temple Judaism, the idea of angels being physically able to impregnate women, and marrying them to do so, seems absurd. If that is discounted, then the text at least hints that within a few generations from Adam the race could be divided sharply in two this way. One simple answer is that Adam’s line was, within this narrative, distinct from the rest of mankind.

- Similar considerations apply to the infamous Nephilim, who seem from 6.4 to have been around even before the preceding episode. They were “the heroes of old, men of renown”, so they were human. But, again within a few recorded generations from Adam, they deserved their own special name apparently denoting they were giants, in stature or deed. How do they fit into Adam’s genealogy? Was Noah one of them? Surely not – they’re far more likely, it seems to me, to come from other stock with relevance to this old and, to us, rather opaque narrative.

To all this, of course we must add the extra-biblical testimony of both history and archaeology about a world already well-populated in the historical times fairly clearly indicated in Genesis. Yesterday I sought out a neolithic long barrow not far from us, dated to around 6,000 years ago. Its builders, it’s thought, may have originally been immigrants from, ultimately, the middle east, but we only suspect that because Britain has older mesolithic settlements going back to the end of the ice age, and even 40,000 years earlier Europe has a rich cultural heritage in haven-areas free of ice. I’ve visited their caves and seen their artifacts in France.

It may be plausible to argue that Genesis represents some mythic representation of the whole of mankind, but it’s not plausible to take the geographical and historical clues in Genesis and then say that the Cro-Magnon or Aurignacian cultures post-date a Flood in the last few millennia, a countable number of generations after Adam and before Abraham.

Such problems all disappear entirely if we take it that Genesis specifically mentions only Adam’s line because only Adam’s line tells the story of Yahweh’s dealings with the ancestors of Israel. Israel was being told that it was already part of the story of the true God’s dealings with mankind, as well as being warned that just as Adam had failed and brought much grief on the world, so might they fail to be faithful and secure God’s blessing. Not for nothing does so much in the account of the Fall mirror the story of the Exodus, and the Exile – this does not mean that the former was simply invented to illustrate the latter, but it is archetypal.

The big question then becomes how God carried on the story of his first representative, Adam, so that it became relevant not only to the nation of Israel, but to every human being under heaven. That’s for another time, but it’s not intrinsically more difficult a question than how the promised King of the Jews, Jesus Christ (son of Abraham, son of David and son of Adam) should become king of the whole cosmos.

When cain marrtied his wife it seems to be after killing abel. that was well over a hundred years as eve got another son to replace abel and his timeline is given.

So in a 120 years or so lots of girls were born. cain married a wife. there was no other sources for people by biblical accounts.

No names but Abram left GODS to follow the real God. I don’t see a need for names.

Remember critics who deny the bible would say its impossible for the writers to know the names of Gods so long before they wrote the bible.

The names actually do show the bible was recording exactly what it said it was.

A well-done defense of your view of Genesis. It is curious that the names of other gods are not mentioned. I’d ever noticed that before, either.

I’m curious how you reconcile these two things:

And likewise, in the period of history after the Flood, and probably before if it is the same Flood as that of the cuneiform texts, we know there were whole nations of people worshipping them, rather than Yahweh (who is unknown, it seems, from that period from outside sources).”

“at that time men began to call on the name of Yahweh”. Which men would those be? In Genesis, the phrase “calling on the name of the Lord” seems usually to imply sacrificing to him as Abraham did. But Adam knew Yahweh, and we know that both Cain and Abel sacrified to him. It’s hard to believe that Seth or his family didn’t, and even if they began later in life, they wouldn’t be the first to do so. The verse, then, appears to suggest that some outsiders began to worship Yahweh either under his covenant name, or at least in substance.

Not trying to find fault. Just curious if you have a speculation.

Hi Jay

Well, it would be speculation, since the text is both highly compressed and assumes many things no longer easily accessible to us.

But my speculation is that there were those outside the Adamic line who, as in all times, found truth in this pure concept of God (whether or not he was known by name). In other words, the text is telling us that the worship of the true God always continued amongst some people (and notably the “holy line”). They would not have to be a majority, or even recorded in extant texts at all.

I’m not really satisfied by the traditional explanation that this verse refers to when “public worship” began amongst the descendants of Adam (which, of course, was taken to be the whole of humanity). There would seem little point in mentioning that.

Thereafter, of course, the Flood proves that “the whole earth corrupted itself”. Syncretism is at least implicit in the run-up to Abraham’s call, even in his line. One wonders if that might take the form of angels or deities under God multiplying and becoming the objects of worship – in Mesopotamnia the sky god Anu was effectively, it seems, promoted out of involvement with the world.

Another, tangential, thought is the way that “El” was widely worshipped across the near east – Baal, I believe, was held to be his son and took over the business. Given the table of nations, maybe the Patriarchs recognised some residuum of true religion amongst the people they met, and vice versa. We have, after all, the recognition by Abraham of Melchizedek as a legitimate priest of God.

Speculation ends!

Hi Jon,

Commenting on an old post:

I believe I’ve read that the verse “at that time men began to call on the name of Yahweh” contains the 70th reference to God in Genesis. As the writer was keenly aware of numerical patterns, this would be a major highlight of the text. Indeed, people calling upon God takes a prominent place in the rest of Scripture, especially in contrast to the time of the deluge.

Ron

That’s interesting Ron. I’m too lazy to count to confirm it, but the Pentateuch is chock full of those numerological constructions, and they’re useful in helping confirm what is significant.

I’m not sure what lesson to take from the highlighting, though. Any ideas yourself?