One interesting aspect of Dante’s Divine Comedy (around which to reading I’ve finally got…) is to see the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas being applied just a few decades after his death, when it was still new and controversial. Thomas actually makes an appearance in heaven, but spends the majority of his speech eulogising St Francis of Assisi, which is not improbable given the priority he put on faith over philosophyat the close of his life. One thing that Dante deals with is the Great Chain of Being, a key mediaeval idea which I wrote about here.

In the context of the Divine Comedy, Dante uses the idea to account for the imperfections of nature. That which is made directly by God in creation is (according to that philosophy) necessarily perfect and also incorruptible. But secondary causes, responsible for natural processes such as generation, may sometimes fail, which explains why there are, for example, deformed animals born. It also explains the existence of death and decay in the world.

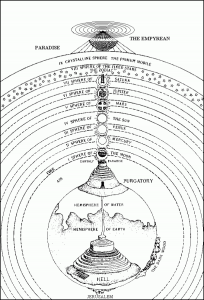

The kind of secondary causes envisaged involve the “heirarchy of being” of the universe, so that God, the Prime Mover of every action, operates first through the movement of the outer circle of heaven, the primum mobile, from which derive the movements of the inner spheres of heaven, and they in turn influence what happens in the lower realm of earth. Such events therefore come from God indirectly by “generation” rather than “creation”. The translator of my version explains this indirect work of God in his notes as the “physical, chemical and biological laws of nature”, and although that is anachronistic to mediaeval science, in metaphysical terms it describes the interaction of God with nature in terms that could be applied today: secondary causes produce less than perfect outcomes.

Now, at first sight it might appear that this 13th century, thoroughly Christian, concept shows that the Creationist insistence on special creation is a recent thing, for nature had great “co-creative” powers even in mediaeval Christianity. This however is far from the case: Dante speaks of the heavens as being perfect (because created directly by God), and also the eternal souls of men and angels, because, in line with the philosophy, intellect can only come from God himself and is incorruptible. Hence the Catholic doctrine that the bodies of men come through natural generation, and so may suffer corruption, whereas the soul is immortal – and eventually will even bring new life to the resurrected body. Christ, too, is incorruptible and perfect because he comes directly from God.

But here’s the thing – so too was Adam, because he was created by God directly. I suppose that the whole initial, Genesis 1, creation would also be deemed perfect by this reasoning (unless the commands “Let the earth bring forth…” were taken then, as sometimes now, to indicate the use of secondary causes). So the Creationists are quite in line with Aquinas in believing in an initial, direct, creation by God, and “creation” (actually “generation”) nowadays only through the secondary causes known to science.

This whole system arises from Aristotle, who was no fool, but who attributed great intrinsic powers to nature rather than to God. But as developed by Aquinas it doesn’t appear to contradict Scripture, though it certainly doesn’t arise from it, nor from empirical science. But it does make a whole raft of assumptions based on reasoning apart from revelation or observation, and some of these were challenged with the rise of early modern science via Descartes and Bacon and, especially, the “mechanical philosophers” like Robert Boyle, who were all distinctly anti-Aristotelian.

In particular, in the present context, they rejected the idea of “mysterious action at a distance” that lay behind the principle of the influence of the spheres, in favour of exclusively mechanical effects of particles colliding with other particles – though that didn’t prevent people like Kepler and Galileo making their living from astrology. It was Newton who re-introduced spooky action at a distance in the form of gravity, but the mechanical philosophers overall retained the “trickle down” effect of divine action only in the much attenuated form of laws of nature, somehow obeyed by the particles much as obedient subjects keep the laws of a distant emperor.

But though the disruption of the scholastics’ Great Chain of Being is heralded as an achievement of modern science, what is less often noticed is that one big Aristotelian assumption – that of the power of secondary causes to cause all earthly events – was retained by modern science. Aquinas and other scholastics had integrated God into Aristotle’s effectively atheistic system by placing him as the indispensible Prime Mover at the start of the causal chain, but though, like Boyle, they retained a strong doctrine of providence, this was almost an adjunct to the system of secondary causes operating far down the chain of being. The moderns broke the chain only by creating a huge gulf bridged solely by the laws of God.

Now it was by this route – the retention of an originally non-Christian Greek view of a causally richly endowed natural realm far below God – that God eventually came to be written out of the essential governance of the world. Consider an analogy.

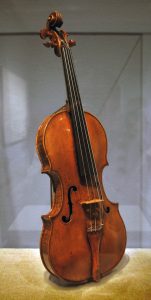

Tradition suggests that the violin was invented in response to the desire of an Italian ruler for a relatively cheap and simple bowed instrument that could not only be used in consorts at court, but would be easily mastered by vernacular musicians in communities. So it was conceived, it is said, as a kind of Volkswagen of the musical world. This final goal was, again by tradition, given as a commission to Andrea Amati (1511-77), who in order to achieve it employed his knowledge of both instrument making and acoustics to produce what was essentially the instrument we know today, despite the improvements made by later makers like Guaneri and Stradivarii and their successors. Even the earliest Amatis look pretty like modern violins, and that’s probably because a lot of Pythagorean mathematical theory went into designing the instrument even before the first models, rather than simple trial and error with ever-changing prototypes.

The violin, like the Fender Stratocaster or the Bic ball-pen, is an example of how a genius simply got it right, more or less first time around. If you want to tell the story of the creation of the violin, it would be impossible to do it any justice without fully considering those highly teleological final and formal causes. The violin exists because Amati set out to achieve a goal, considered in what form it could best be achieved, and succeeded. The practical skills of him as a luthier were also important of course, in the selection of woods, the knowledge of how to season and carve it, and so on. But these would be almost taken for granted in ones account, since presumably they were skills formerly involved in making viols and other less iconic musical instruments for generations before.

However, our story would be very different if we wanted to explain the mass production of violins in, say, South Korea, several centuries down the line. Now, I suspect that even the cheapest violins, in practice, use quite a lot of human handiwork – it’s just less skilled, less well-paid and less subject to quality control than that of the master-craftsman from Cremona. But for the sake of the illustration, we’ll assume that an industrialist has automated more or less the whole process. Logs are sawn by machine, selected for suitability for various tasks by photoelectric sensors, shaped and routed on a jig, assembled and glued by machine and varnished in the mass. Quite possibly, they make excellent student instruments, though seldom if ever wonderful ones.

The story that’s of interest here is how the machine-shop actually works, what the computer algorithms do, how errors are corrected, and so on – in other words, the chain of efficient material causes that turn a lump of wood into an instrument. Behind this, of course, lies not only several centuries of the luthier’s and musician’s experience, but a whole team of people designing the robotics necessary to achieve what is still, in the end, a design goal. But because the creative process has been so divorced from the manufacturing process, as compared to being a fly on the wall as Andrea Amati strove to meet the Duke’s ambition, in the case of the production line it’s possible to think as if finality and form can be left out of the story. It’s all about wonderful robots instead.

The story that’s of interest here is how the machine-shop actually works, what the computer algorithms do, how errors are corrected, and so on – in other words, the chain of efficient material causes that turn a lump of wood into an instrument. Behind this, of course, lies not only several centuries of the luthier’s and musician’s experience, but a whole team of people designing the robotics necessary to achieve what is still, in the end, a design goal. But because the creative process has been so divorced from the manufacturing process, as compared to being a fly on the wall as Andrea Amati strove to meet the Duke’s ambition, in the case of the production line it’s possible to think as if finality and form can be left out of the story. It’s all about wonderful robots instead.

In the same way, the assumption that causes within nature are, in practice, very far removed from the personal involvement of the Creator is necessary if science as “the study of efficient causes” is to tell any kind of complete truth about things in the world. But that assumption, as I have suggested, is merely a carry-over into the mechanical philosophy of an earlier assumption derived, ultimately, from Aristotle: that of a chain of being stretching from the highest and purest powers – God in the interpretation of Aquinas or Dante – down to lower and corruptible powers in the events on earth that do the day-to-day dirty work.

But why should that be true? Aristotle’s philosophy, once Christianised, did not blatantly contradict the Scriptural revelation by God’s Spirit, but I would argue that it by no means represents it fairly. As I suggested in my last post, teleology appears to be inherent within nature (agreeing with Aristotle, and contradicting Descartes), and on a dispassionate reading appears also to be affirmed in Scripture – to a degree. But the Bible also strongly teaches about a God who is personally involved in both natural and human affairs, not at the top end of a flexible chain of being, but imminently, through the Logos, the Son, who is the fully-sufficient mediator between the Father and the world that was made in, through and for the Son, and by the involvement of his Spirit.

How close is the involvement of Christ the Logos to the activities of nature? According to current science, about the same distance as you find between Andrea Amati and a Korean student fiddle. But by what reasoning do we exclude the very possibility that a better analogy is that of the relationship between Amati the craftsman and his lifetime’s output of original masterpieces?

Hi Jon,

I read parts of Dante (Divine Comedy) many years ago, and I remain impressed with the poetry, the way he presents his view within a “cosmological setting” (which I assume was the current one of his day. Above all, a lasting impression was the way he integrated his theology (be it hell, purgatory, and heaven) with the human condition. An impressive intellect.

Hi GD

It’s a long overdue filling of a gap in my non-literary education. I agree with your assessment, which of course reminds us that such intellects arise only within a rich intellectual climate, which could teach us a lot that we’ve forgotten.

It was a roman catholic world. So very easily they rejected actual biblical truths OR invented other truths and raised them to a level with biblical authority.

Its not christian but ideas in need of reforming. it just also affected these matters.