I’m pretty sure a new word is soon going to become part of the English language: “zoomed-out.” I keep hearing the concept, if not always the phrase, used by people who are, ostensibly, doing reasonably well under lockdown. Whether it’s our own student pastor, doing all his church and college work on a screen, or historian Neil Oliver comparing dreary lockdown life with the buzz he felt from a live audience on a book tour before all this, or even my old school-fellow J. J. Burnel commenting ruefully on trying to compose a new Stranglers album via Zoom (having sadly lost his friend and keyboard player, Dave Greenfield, to COVID last year); never wanting to see another Zoom screen seems increasingly common. Someone has commented that lockdowns would never even have been conceived apart from internet conferencing.

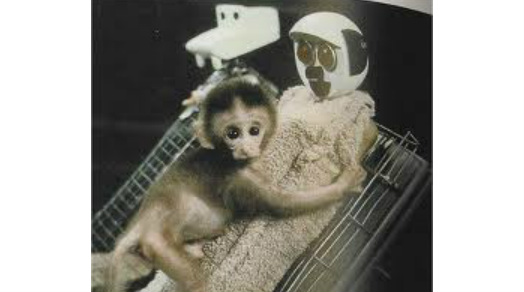

I also think of the children, especially my own grandchildren. When I watch a video like this, for some reason I keep going back to an image from my social psychology studies at Cambridge – that of the experiment discussed as “Harlow’s monkeys.”

This rather sad experiment involved poor baby rhesus monkeys put into a bare cage, and offered a wire mannikin with a teat and milk, or in subsequent experiments that plus the more lifelike and cuddly artificial mother shown, without a feeding teat. The experiments showed that those monkeys given entirely adequate feed, but only a wire frame to cuddle, developed highly abnormally and failed to thrive. When the soft mother-substitute was added, not only did baby monkeys show a strong preference for it, separating only for the minimum time when hungry, but they developed more normally.

The name inextricably linked with this in my memory is John Bowlby, whose work on infant attachment Harlow’s experiment confirmed. Trained as a psychoanalyst, Bowlby’s work on delinquent evacuee children during the war led him (to the great hostility of his Freudian colleagues) to reject unconscious fantasies as a cause, when he found a strong correlation between delinquency and early maternal separation. In the developed form of attachment theory, to cite Wikipedia:

1 Children between 6 and 30 months are very likely to form emotional attachments to familiar caregivers, especially if the adults are sensitive and responsive to child communications.

2 The emotional attachments of young children are shown behaviourally in their preferences for particular familiar people; their tendency to seek proximity to those people, especially in times of distress; and their ability to use the familiar adults as a secure base from which to explore the environment.

3 The formation of emotional attachments contributes to the foundation of later emotional and personality development, and the type of behaviour toward familiar adults shown by toddlers has some continuity with the social behaviours they will show later in life.

4 Events that interfere with attachment, such as abrupt separation of the toddler from familiar people or the significant inability of carers to be sensitive, responsive or consistent in their interactions, have short-term and possible long-term negative impacts on the child's emotional and cognitive life. Harlow’s work shows the necessary physicality of these attachments in rhesus monkeys, but you will also remember those harrowing images of children in Romanian orphanages of the Soviet era, whose entire development was stunted by the paucity of human contact. Sociologically, too, early family breakup is known to be associated with multiple adverse effects (though that evidence is habitually ignored by ideologically motivated politicians convinced that all social problems are due to the nuclear family).

It is consistent with Bowlby’s research that within a day or so of birth babies, who are pretty myopic at this stage, respond to their mother’s face as she feeds them, and within days are showing signs of mimicking her expressions. Personhood begins in face-to-face contact.

Bowlby concentrated on the crucial period of initial development, and indeed it was of him, back in 1973, that I first heard the criticism, “Like all great researchers, he overstates his case.” But his emphasis on the centrality of “proximity” (for which read “hugs”) in that initial development should give us clues about the whole nature of human interactions. Wikipedia again:

As the toddler grows, it uses its attachment figure or figures as a “secure base” from which to explore. Mary Ainsworth used this feature in addition to “stranger wariness” and reunion behaviours, other features of attachment behaviour, to develop a research tool called the “strange situation” for developing and classifying different attachment styles.

The attachment process is not gender specific as infants will form attachments to any consistent caregiver who is sensitive and responsive in social interactions with the infant. The quality of the social engagement appears to be more influential than amount of time spent.

This should alert us to why the physical proximity of a living teacher matters to kids who are learning, quite apart from better discipline or more effective feedback, and likewise the importance of physical contact with other trusted adults, such as grandparents.

It is sobering to reflect on Bowlby’s discovery of a “developmental window of opportunity” for the initial socialisation process, up to 30 months, if major developmental problems are to be avoided. Other researchers have found similar “windows of opportunity” for acquisition of language – feral children raised by wolves or sheep can never learn to speak.

But what about the more subtle, later stages of socialisation that make for fully functioning, happy people, rather than simply preventing psychopathy? Would one not anticipate some permanent adverse consequences in social development if children’s developing brains are denied normal, real human contact for, say, a whole year? And given the importance of the human face to early socialisation, would we not be asking for trouble if children only saw masked faces over that time? Given the way the initial human contact forms the whole basis of social development, it may also be vital, rather than merely desirable, that children have actual contact with friends of similar age. Playgrounds and classrooms create human beings: computers cannot.

Roger Scruton wrote, wisely, to the effect that the face is the window to our soul. Or as Orual says in C. S. Lewis’s novel (only slightly taken out of context):

“How can [the gods] meet us face to face till we have faces?”

If lockdown induces “Zoom-fatigue” (or solitary confinement syndrome for the poor who have no access to Zoom), then the brief respites from it we have experienced have also been marred by the de-socialising requirement for masks. If we never meet, or touch, a real human being with a real face, serious deprivation is occurring. Mental ill-health is one result – but in children it could potentially have permanent developmental effects.

I learned the universal importance of physical contact on my first house job as a doctor. I admitted an elderly lady who lived alone, and so of course I did the usual physical examination, taking her pulse and so on. And as I did so she said, very sadly, that I was the first person who had touched her for years, and it made her feel human again. I can’t say I made a point of taking her pulse every time I passed from then on (though maybe it would have been better if I had), but it sowed another seed in my mind about the importance of our being physical beings made human by mutual contact, both by touch and facial expression. Our age is unique, and misguided, in thinking we can reduce the social to verbal communication.

All of that makes me wonder about those eminent scientists who, from the very start of the COVID pandemic, were stating enthusiastically that shaking hands was now a thing of the past or that mask wearing was a precaution that should become permanent. The WHO are now saying that social distancing and mask-wearing must continue everywhere until everyone in the world (including, presumably, both antisocia class-enemies and isolated Amazon tribes). Likewise I’m curious about the statement apparently made in Klaus Schwab’s book The Great Reset that education by virtual lessons is the ideal pattern of the brave new future. Far be it from me to perform armchair diagnosis, but you have to ask what was happening to these guys in the first thirty months of their childhood.

It’s good (in a sombre way) to hear others who are experts in the field agreeing with the conclusions one has come to. Here is a head teacher coming at several of the above points from a different angle, but with equally serious conclusions about the permanent damage of locking down children of all ages.

He cites particularly the lost opportunities of teenagers, the lost socialisation of 6 and 7 year olds (and their indoctrination with “the language of death” on all sides) and the damage in the “Bowlby window” of children born last year who have never seen an unmasked human face apart from their parents.