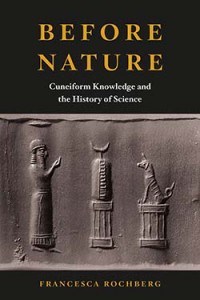

Preston Garrison recently sent me (courtesy of Ted Davis) an interesting review (limited access – sorry) for a forthcoming academic tome on Babylonian science, knowing I’d be interested both because of my musings on what science is, and what it isn’t, and also because it has implications for interpreting the early chapters of Genesis. I’m tempted to buy it when it comes out, despite the price and having to learn cuneiform(!), but meanwhile some thoughts.

The author, Francesca Rochberg, is an assyriologist and science historian (with an interest in the science-religion interface and in philosophy – how relevant is all that to origins studies!) And she writes novels too. The first thing that struck me in the review is her contention that the Babylonians did good “science” (obviously that word needs unpacking) without any concept whatsoever of “nature” as an overall entity – a concept that came only from later Greek culture:

The author, Francesca Rochberg, is an assyriologist and science historian (with an interest in the science-religion interface and in philosophy – how relevant is all that to origins studies!) And she writes novels too. The first thing that struck me in the review is her contention that the Babylonians did good “science” (obviously that word needs unpacking) without any concept whatsoever of “nature” as an overall entity – a concept that came only from later Greek culture:

Rochberg argues that the cuneiform world’s preoccupation with divination, ritual, and incantation was motivated by a determination to establish “norms and anomalies within meaningful categories” and that this goal is inherently scientific. In a chapter entitled, “The Babylonians and the Rational,” she also argues that “magic” should not be used as a tool for separating science from nonscience because, in the cuneiform world, magic belonged neither to the natural nor to the supernatural. Three subsequent chapters develop these theses.

I’ve pointed out before that even early modern science saw magic as part of science, rather than of supernature. But the really provocative thing is that by comparing such an ancient scientific culture with ours she can show how much our science, far from being an objective discovery of “what is out there”, is in fact a culture-bound pursuit. Even the central concept of “nature” as a system to be investigated is a human imposition on the world:

Before Nature’s formidable erudition will fascinate cuneiformists while daunting nonspecialists and disturbing scientists, who will likely recoil from regarding divination as part of science. For noncuneiformists, the book’s most compelling parts will be its discussions of western civilization’s philosophical attempts to define nature, postdating the cuneiform world—from Aristotle to Einstein and his successors. “Real and independent as we may think nature and its orderliness are, the very notion of physical phenomena being subject to laws is a profoundly cultural claim, one that imparts a human value to the world external to human society,” argues Rochberg.

This of course does not make modern science “wrong” or “useless” – but it does make it profoundly human, just as Babylonian science was, but in a vastly different form. And that obliges us to view its assumptions and limitations more critically.

However, putting that “Philosophy of Science” issue to one side, I was drawn particularly to one statement in the review in particular:

The Babylonians’ understanding of the heavens—including astronomical predictions—did not derive from any physical framework. They employed no classification of the Moon and planets as natural phenomena and conceived no physical laws of nature governing those bodies’ cyclical appearances. Neither had they any concept of a geometrical geocentric cosmos.

This is relevant because our biblical creation story, and the subsequent early chapters of Genesis, have close links to the Babylonian mindset, and on any dating must arise from an ANE worldview predating the Greek concept of “cosmos”. However, note that any NT and Patristic commentary on Genesis, by contrast, comes from a world thoroughly familiar with “the world” or even “the universe” in the sense of “global totality”, that we share, albeit they had a geocentric system.

This is relevant because our biblical creation story, and the subsequent early chapters of Genesis, have close links to the Babylonian mindset, and on any dating must arise from an ANE worldview predating the Greek concept of “cosmos”. However, note that any NT and Patristic commentary on Genesis, by contrast, comes from a world thoroughly familiar with “the world” or even “the universe” in the sense of “global totality”, that we share, albeit they had a geocentric system.

One interesting example I found of this is that the Greek Septuagint Bible, from the Hellenistic era, translates “earth” (eretz) in Genesis 1 correctly and consistently as ge (arable ground) except in 2.1, the summary of creation, where it uses “cosmos“, though the Hebrew is, as always, eretz. The change makes theological sense in a culture that sees God as the creator of “planet earth” rather than only “functional land”, but we need to understand that the writer of Genesis could have had no such clearly global conception. He was thinking more about how all functional elements of the “temple of creation” – ground, sea, sky, light, food, livestock or man – were completed, rather than writing of a completed universe.

We therefore need some careful thought in how we understand Genesis (a) in its original setting, (b) in its New Testament understanding and (c) in relation to modern scientific and theological concepts. That seems a mountainous task, except that if we accept the divine inspiration of the text, such translation between worldviews must be possible. I’ll mention some implications in a bit.

But first, in the absence of access to Rochberg’s book, here’s what seems a similar case made more fully by a Catholic philosopher, Remi Brague, of which this long quote speaks:

For Brague, the primary foundations of cosmology, as well as its limits, lie within the origin of the word ‘cosmos’ in the ancient Greek civilisation. As a result, a distinction and separation is made between the moment where a word to mean “the world” – cosmos – came into being and the previous conditions set by pre-Greek civilisations… Brague shows evidence that leads to the conclusion that early civilisations, as the Mesopotamian and Egyptian, did not have a word such as world in order to designate the entirety of all things that constitutes a world. Previous to the Greek civilisation, on a first stage, there existed enumeration – the listing of elements that made the whole – after the utterance of the whole – the usage of words that meant entirety and wholeness, expressing therefore the idea of a totality (Brague, 2003; Rochberg, 2007). According to Brague, this meant that these civilisations had not yet grasped things in themselves in order to create a structure that makes of all things a unity. Phenomena were observed, understood, explained and integrated in an overall system without, however, Man looking to understand them as a unity from a single perspective; what Emma Brunner-Traut designated as ‘aspective’ (Brunner-Traut cited in Brague, 2003, p. 13)… because in pre-Greek civilisations Man existed in communion with the world, such an independent structure could not be conceptualised and named. Consequently, without a word for world there could not exist an explicit and intentional reflection upon it. As such, following Brague’s argument, it is not feasible to discuss cosmology prior to the existence of the word cosmos, which in the Western world only came into being with the ancient Greek civilisation.

What that means is that to speak of “Babylonian cosmology” or the “cosmology of Genesis” in the sense of “ancient science” is anachronistic. The idea that either culture conceived of a flat world with a goldfish-bowl-like raqia (hard firmament) above the air keeping out an infinite ocean must be wrong, not because any individual element is necessarily mistaken, but because the whole idea of the “world” as a physical whole did not exist (incidentally, neither did the the idea of “infinity” or the idea of “air” as a material thing (see here).

Likewise, the argument over whether Genesis conceives a worldwide or local flood is quickly resolved – one cannot think about a worldwide flood when one has no concept of “world”. There are implications for how Genesis would have understood “mankind”, even (or maybe especially) assuming the early chapters conceive of people outside the Adamic line like Cain’s wife. What does the universality of sin mean in a time before such universals became thinkable?

Likewise, the argument over whether Genesis conceives a worldwide or local flood is quickly resolved – one cannot think about a worldwide flood when one has no concept of “world”. There are implications for how Genesis would have understood “mankind”, even (or maybe especially) assuming the early chapters conceive of people outside the Adamic line like Cain’s wife. What does the universality of sin mean in a time before such universals became thinkable?

Such a lack of a “cosmic” concept helps account for the parochial nature of the Babylonian “first world map”, which I discussed here. We are wont to assume the ancients were ignorant of the world beyond their experience: rather, such a world beyond is ignored on principle in favour of what is relevant to experience. I tried to argue that with reference to Genesis 1 here. The text works perfectly well without any concept of “cosmos”, “nature” or “world”- which is just as well, if such ideas didn’t exist back then.

Because it’s so hard for us moderns not to exclaim, “Oh, they must have had some picture of what the whole shebang was really like”, I’ve been trying to think of examples of things we are happy to regard without any idea of a “totality”.

One area might be music. To us, there is a world of music we know, whose boundaries are extended in a trivial way by the latest single, or in more dramatic ways by avant garde experimenters. We’ll hear music of other cultures or times with a mixture of familiarity and strangeness. We’ll maybe in a curmudgeonly partisan way doubt that hip-hop or blue-grass or Ligeti is music at all. But we’ll never consider that there is, in any real way, a bounded “universe” of music of which we could, perhaps, explore the boundary without following a path from where we are. Occasionally, people will excuse plagiarism on the grounds that there are only so many combinations possible of our 12 notes – but scientists don’t seriously calculate the total number of tunes or rhythms there may be, as they do the number of elementary particles or Planck times in the universe.

Yet it’s quite possible to conceive of an alien culture that did that exercise as serious science with regard to music – and when they contacted us and asked exactly which part of the music-universe we occupied, we’d answer that we’d never thought to wonder.

A second example might be easier to relate to the ANE worldview. Did you ever stop to wonder, when reading the stories to your kids, about the cosmology of Narnia? I’ll bet the answer is “No”. And yet there’s every reason to think it’s nothing like ours. It’s in some other parallel dimension, apparently – you reach it through the back of a wardrobe, for goodness’ sake. We’re aware it has landscape and territories which can be ruled by good or evil folk. It has seas to be navigated and mountains to climb. But how big is it? Being a magic place, why should it even be a sphere, like our world? After all, stars like Ramandu go there to retire, rather than become red giants or supernovae as they would here.

A second example might be easier to relate to the ANE worldview. Did you ever stop to wonder, when reading the stories to your kids, about the cosmology of Narnia? I’ll bet the answer is “No”. And yet there’s every reason to think it’s nothing like ours. It’s in some other parallel dimension, apparently – you reach it through the back of a wardrobe, for goodness’ sake. We’re aware it has landscape and territories which can be ruled by good or evil folk. It has seas to be navigated and mountains to climb. But how big is it? Being a magic place, why should it even be a sphere, like our world? After all, stars like Ramandu go there to retire, rather than become red giants or supernovae as they would here.

But I’ll wager we’ve all been quite content to concentrate on what matters in the stories: the experience of the characters, the struggle between good and evil, and the salvation of Aslan. It’s not that we assumed Narnia would be more or less the same kind of thing, in the same kind of galaxy, as earth is. We just didn’t assume anything, nor recriminate C S Lewis for failing to deal with the issue.

I suggest that’s the kind of mindset (with a whole bunch of other big differences regarding the nature of nature) shared both by our Babylonian scientific ancestors and our ancient Israelite spiritual forbears.

The difference is that understanding Babylonian science is, for the most part, an academic exercise. Whereas the unfamiliar worldview of Genesis needs to be understood better if we are to understand the foundations of our faith in creation, election and sin. Their world changed into our world – and all the time it was the same world to God.

There is no such thing as science. Science doesn’t exist outside of humans.

All there is IS truth about nature. Accuracy on any point about it. so people try to figure it out and rearrange it for fun and profit.

Science is just a word about accuracy in conclusions and accuracy in methodology before conclusions drawn.

In origin matters its simply the people who are inaccurate. not the science

I don’t think the BabyloniansWhen it was right called themselves that.

However these people did do science or rather figure things out.

When it was accurate. Just not very much but more then others.

Hi Jon,

I’m always interested in such things. Our society certainly thinks it has arrived – we clearly understand much more than those of yesteryear because of our advanced technical and scientific ways (wink, wink). Magic is a thing of the past – unless you include modern book and movie trends! 😉

However, I have learned to be cautious because writers of ancient civilizations can easily inject their own views into the mix. I believe Walton does this with some of his constructs of ancient thought. Also, just because we have a more succinct, linguistic understanding of a concept than others does not necessarily mean we comprehend it more or they understand it less. Someone DID invent the word “cosmos” at some time so you can be sure that thoughts about it existed BEFORE the word did.

This is not to say that the ancient Hebrews understood the cosmos as we do. But to say they couldn’t think about it is out of line. Sometimes people go too far with this. Language gives symbolic representation to our thoughts. Artists and musicians can communicate without words. “The philosopher Peter Carruthers has argued that there is a type of inner, explicitly linguistic thinking that allows us to bring our own thoughts into conscious awareness. We may be able to think without language, but language lets us know that we are thinking.” (http://mentalfloss.com) Food for thought.

We are made in God’s image and I believe our creativity is rooted from there. That has some implications for the matter at hand. While we perceive some details of the “cosmos” more than the ancients, that doesn’t mean they didn’t comprehend anything about it at all. Let anyone stare at a crisp night sky and try not to think.

Medical examples abound: Mesentery (now an organ!) and what about SAD, SIDS and CFS? Clearly we had thoughts about these things before the words existed. Perhaps not as sophisticated or nuanced but thoughts none-the-less.

Just because I speak English doesn’t mean I don’t understand something about the following concepts (Altalang.com):

Tartle: Scottish – The act of hesitating while introducing someone because you’ve forgotten their name.

Torschlusspanik: German – Translated literally, this word means “gate-closing panic,” but its contextual meaning refers to the fear of diminishing opportunities as one ages.

Wabi-Sabi: Japanese – A way of living that focuses on finding beauty within the imperfections of life and accepting peacefully the natural cycle of growth and decay.

Dépaysement: French – The feeling that comes from not being in one’s home country.

Thoughts that “without a word for world there could not exist an explicit and intentional reflection upon it” are overstating things. They might not have known about Kepler’s laws and supernovae but the ancient Hebrews clearly knew the stars were other than the “eretz” because they were not given dominion over them. That certainly distinguishes them in some sense. And this book on the Babylonians probably confirms that they did as well.

I think I ranted a bit there but I hope you’ll forgive me.

Hi Ron

As I was writing I had at the back of my mind the caveat that vocabulary does not determine thought quite as strictly as Brague seems to imply. But there’s an interplay between what means of expression there are and what is commonly or clearly expressed. I like your quote: “We may be able to think without language, but language lets us know that we are thinking.” A more recent example of that is how much the differences between Eastern and Western theology were affected by speaking Greek and Latin respectively: seldom was mutual understanding complete, though there was convergence on most of what mattered.

Rochberg’s case, I think, is what the evidence from her literature shows about what was expressed in the ANE: the Greek cosmos was an idea that developed along with the coining (or more probably the appropriation) of the word, just as (in my linked article) “air” became applied for the first time to a substance, and slowly lost its former meaning. Understanding their difference in perception doesn’t denigrate them – it enriches us.

You can see in the Greek words traces of how “the world” was conceived before it was accepted as a material globe and a complete system as “cosmos”, which derives from “an orderly arrangement”. “Aeon”, though, comes from “an age”; “ge” from soil, and “oikoumene” from an inhabited place, all of which have to do with things other than totality, especially physical totality.

The same is true in the English words, presumably reflecting Anglo-saxon worldviews: “world” apparently derives, like “aeon”, from “age of man”, and “earth”, of course, from “soil”. Funny that our names for the planet, “Earth” and “Terra”, both reflect our prehistoric dependence on soil, ignoring the sea, the rocks, the atmosphere, the people, the ecology and so on. Like the Greeks, we’ve managed the change by largely dividing the original meanings from the global ones, so we somehow avoid thinking that “Earth” means “earth”… and we’ve forgotten the temporal connotations of “world” altogether, using it willy nilly for the planet, the universe, human society etc etc.

I find the same process in the Hebrew, encouraging me to think that the “world” in Genesis is, as Rochberg suggests of the Babylonians, thought of primarily in terms of the relationships of its elements, not the totality (this does relate to Walton’s “functional” concept – I think, if anything, he hasn’t taken into account this “a-cosmological” way of conceiving the world, which given his emphasis on temple imagery is perhaps surprising).

So the relevant Hebrew words all have these non-global etymologies, which I suspect are used “literally” in the more ancient texts, but which no doubt acquired broader meanings in the later millennia:

eretz – land or soil

cheled and olam – age

tebel – inhabited/productive land

It’s even more confusing to our understanding of Genesis that “adamah” (soil) and “ara” (land) are interchanged with “eretz”, and that where the eretz is exposed and dries out it is called “yabbashah” (dry land). Personally, I think the text becomes much clearer when one leaves “cosmos” or “world” out altogether.

I’m interested in your medical examples – partly because I had thoughts this week about what a difference it makes to think of the mesentery as an organ rather than as only stuff-between-organs. I think I’d disagree with you, to an extent, in that the medical terms do tend to determine how – and even if – we think about things.

For example, having a particular interest in CFS (and establishing the first, if sadly shortlived, multidisciplinary team in UK general practice to deal with it!), I’ve heard people arguing that it’s new, and therefore imaginary, whereas it probably maps closely to neurasthenia. But this was thought in 1829 (before which it didn’t exist as a disease!) to be a physical weakness of nerve tissue (and therefore respectable when Florence Nightingale got it) – whereas CFS has tended to be labelled psychopathological and, of course, “ME” as a pseudo-scientific pathology. And “postviral syndrome” makes it slightly respectable and medical again!

CFS? O.k. CSF I could get. CAH, o.k. but what is this? And ME?

Sorry Preston – just speaking in tongues.

Ah – I have the interpretation, I think: “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome”. “Myalgic encephalomyelitis”. “Seasonal Affective Disorder”. “Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.”

You see, true communication leaps across the world … if you’re initiated into the same occult mysteries!

Acronymal Gnosticism. I get it. By the way, there is an interesting looking paper on SIDS in today’s early access papers in European Journal of Human Genetics. Of course, I have only seen the abstract.

I thought they’d abolished SIDS years ago by getting people to ignore the advice they’d been given that science proved placing babies on their stomachs was the only thing to do.

It’s rather odd for people of my generation to see all these new granddaughters looking up at you in their cots… as it must have ebeen for my parents to see our kids on their tums.

But I’m only an ex-gnostic now.

This was interesting:

Previous to the Greek civilisation, on a first stage, there existed enumeration – the listing of elements that made the whole – after the utterance of the whole – the usage of words that meant entirety and wholeness, expressing therefore the idea of a totality (Brague, 2003; Rochberg, 2007). According to Brague, this meant that these civilisations had not yet grasped things in themselves in order to create a structure that makes of all things a unity. Phenomena were observed, understood, explained and integrated in an overall system without, however, Man looking to understand them as a unity from a single perspective; what Emma Brunner-Traut designated as ‘aspective’ (Brunner-Traut cited in Brague, 2003, p. 13)… because in pre-Greek civilisations Man existed in communion with the world, such an independent structure could not be conceptualised and named. Consequently, without a word for world there could not exist an explicit and intentional reflection upon it.

This brings up the question: How does one describe a thing for which no word yet exists? It reminds me of the Elbow lyric “New York Morning”–

The first to put a simple truth in words

Binds the world in a feeling all familiar

As Brague noted in the first sentence, the pre-Greek civilizations, lacking the word/concept cosmos to describe a unitary totality of all that exists, did the best they could with the tools at hand to get across the concept. “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth…” They are using “words that meant entirety and wholeness, expressing therefore the idea of a totality…” Another way of expressing the idea of totality in Hebrew was through repetition. Gen. 1:27 —

So God created mankind in his own image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

We see the same thing in Gen. 7:21-23 —

21 Every living thing that moved on land perished—birds, livestock, wild animals, all the creatures that swarm over the earth, and all mankind. 22 Everything on dry land that had the breath of life in its nostrils died. 23 Every living thing on the face of the earth was wiped out; people and animals and the creatures that move along the ground and the birds were wiped from the earth.

Again, according to Brague, the enumeration and listing of elements is the ANE way of expressing totality where the word for such does not yet exist. In short, at the very least, Brague’s conception is not as decisive as Walton would have it.

I think Ron S. was right when he said, “This is not to say that the ancient Hebrews understood the cosmos as we do. But to say they couldn’t think about it is out of line.”

Hi Jay

First, to defend Walton – unless you’re using another source, he’s not the one citing Brague (in fact, Brague’s subject is only tangentially related to Genesis: his focus is on pre-Greeks in order to write about post-Greeks, but his viewpoint happens to concur with Rochberg’s expert opinion on Babylonian culture, only at greater length than I can cite for her).

I think the question isn’t so much what words prevent you expressing – where there’s a will, there’s a vocabulary – but rather the way you think about things before a word is coined. It’s more that you need neither the word nor the idea until a certain point, because you choose to see the world a different way. You have no need to think of relativity and space-time until you start to monkey with the idea of the speed of light, though you could if you wanted to.

So, as you rightly say, “heaven and earth” in Genesis is a merism representing the entirety by the two extremes. But, I suggest, the kind of entirety intended isn’t that of a unified self-contained material world of a particular shape, size, setting in “space” and so on. You don’t actually need that to think of God as the Creator of all the things that are, or creation as his sacred space like the temple; any more than I need to think of Britain’s situation in the world or the universe to think of God governing all the land, water, air, beasts, people, and of the land being higher than the sea but under the sky and so on. They’re universally true, but I would only conceive them in relation to England if nobody had ever crossed the English Channel.

Somebody tells me there’s a place called “France” where the same relationships apply, and it doesn’t surprise me at all – it just makes the same picture true for a bigger area. Maybe at some point I’ll wonder how many of these lands there are and where they stop, and how many types of animals and races of people there are altogether under the sun, but that’s the point at which I’m beginning to get an interest in “cosmos” – and will coin a word for it, no doubt.

Before that point, if “the world of Noah’s time” (quoting 2 Peter) was just the world of Noah’s people, or of the Israelites who considered themselves his spiritual descendants, then it’s only later folks who have to ask if the table of nations was really intended to include Eskimos, Sherpas and Tierra del Fuegans as descendants of Noah, and their territories as being destroyed in the Flood. It would never have occurred to Noah to wonder.

To comment on your quote from Ron S, the writer of Genesis could well have agreed, “The earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it!” (“earth” – eretz – being defined carefully in Gen 1.10, remember, in fulfilment of the promise of the introduction of v1 saying that God created it!). But he no more needed a cosmological opinion about it than he did to say “The earth is dry land, because God restricted the seas to their domain!”

First, to defend Walton – unless you’re using another source, he’s not the one citing Brague

Yes, I misinterpreted that.

They’re universally true, but I would only conceive them in relation to England if nobody had ever crossed the English Channel.

But on this point, I think you’re overstating the case in regards to how little the peoples of the ANE knew of the world beyond their own immediate borders. For example, the archive at Ebla (northern Syria) dates from around 2500 B.C., and the records indicate that Ebla controlled international trade routes between the Euphrates and the Mediterranean, carrying silver towards Mesopotamia, timber to Mesopotamia and Egypt, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, and Nubian gold from Egypt. This is quite an extensive area, and it follows that those who travelled to Ebla to trade from those regions would tell tales of their own “world” back home. Certainly, the extent of trade indicated in the Ebla archives implies a knowledge of “eretz” that extends far beyond the borders of Mesopotamia.

Jay

In my view your point only confirms my thesis. Did you read what I wrote on the ” first world map”, which although dating from the 8th century, at the point when Assyria was taking over the world, and although uncontroversially of “the known world” shows only a fraction of what its makers must have known?

Yet as far as they are concerned, “the world” is the world that matters to them, for whatever reason. The situation is closely paralleled in the Mesopotamian cosmogenic’theogenic myths, which describe things in apparently universal terms, regarding the creation of man, and so on, but woith the aim of explaining the kinship of their particular cities and titular deities.

It show not that they couldn’t think beyond what they knew, but that they didn’t choose even to think as far as the extent of their knowledge.