In chapters 4-5 of Being as Communion William Dembski leads us towards the introduction of information theory by laying some semi-technical groundwork. “Possible worlds” logic will be familiar (and maybe intimidating) to anyone who has seen its use as a tool of analytic philosophy. Fortunately he uses it sparingly and clearly. “Matrices of possibility” are perhaps less familiar, but are actually another of those concepts that makes sense of so many often cloudy things.

He starts the chapter by putting a name and formal description to what we unconsciously do all the time:

Because the actual world is so large and unwieldy, we never grasp it in its entirety. Instead, we only grasp limited aspects of it. This we do by situating aspects of the world within matrices of possibility. These form conceptual grids for our inquiries about the world. A matrix of possibility… is a collection of possibilities relevant to an enquiry. It provides a window on the actual world. Just as a window always has a frame, and thus views some things but not others, so a matrix of possibility limits inquiry to some aspects of the world, excluding others.

Such a matrix, he explains, gives our enquiries necessary “traction” by, for example, holding some things constant whilst we examine variables, or even just the “informational act” of choosing what we want to look at. Furthermore:

…information is fundamentally relational: the possibilities associated with informatiojn only exist in relation to other possibilities, and thus within a reference class of possibilities… From an information-theoretic point of view, individual possibilities make no sense on their own but only as part of a reference class.

It’s obvious really. The question “What’s that stranger doing in my car?” isn’t interested in most of the truth – he’s sitting, brething, digesting a hamburger, scratching his ear, wearing odd socks – but just in whether or not he’s stealing it.

The first thing I note from this is a theoretical confirmation that discovery (including science, of course) is fundamentally a subjectively human, not a neutral, activity. In philosophy of science terms, all inquiry is “theory-laden”. One chooses the possibilities one wishes to include, expecting that one of them will prove true (the stranger is a car-thief or not).

This reminds me of Michael Polanyi’s understanding of science, which I touched on here. Einstein did not “find” relativity whilst walking across a heath, but in an intuition of genius as a teenager he felt that some such idea must be true, then looked for a new mathematical way of exploring it, by use of which his search proved fruitful. Empirical evidence was only confirmatory (and of course either those experiments were designed within the possibility matrix of relativity, or old experiments were re-interpreted through such a matrix).

Another corollary of this is that, for the most part, you only find what you have visualised in your matrix, and may remain insensible of possibilities outside it. Dembski’s main example for the chapter is a delighful legend of two mediaeval kings throwing dice for ownership of an island. The first king throws a twelve and feels confident. He has no inkling that the other will throw thirteen (I won’t give away how this comes to be!).

To illustrate the concept Dembski deals with this in (simple) mathematical terms in which the first king’s possibility matrix consists of the set {2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12} – reality, as it turned out, included at least one extra possibility, “13”, which he could not have anticipated, having not factored in the possibility that (as Dembski dryly puts it) “his gaming partner happened to be a Christian saint with miraculous powers.”

In that anecdotal case, the first king had no choice but to accept the surprising outcome (as you’ll see if you read the book). But it occurs to me (going beyond Dembski now) that in a more complex reality one is often more likely simply to keep one’s preferred possibility matrix intact, and so never discover the reality at all.

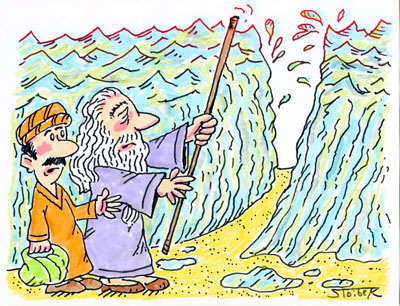

Let me use the old example of methodological naturalism, but to avoid raising scientific hackles I’ll apply it to theology rather than natural science. Elsewhere in fact Dembski does remind readers of the surprising fact that most academic biblical studies are conducted on the principle of methodological naturalism. Therefore, since under materialism predictive prophecy is impossible, any such instances in Scripture with historically verifiable outcomes must postdate those outcomes. Since naturalism excludes the parting of the Red Sea or the raising of the dead, naturalistic explanations for the text must be sought. In Dembski’s usage, MN defines the matrix of possibilities for Biblical studies.

So what if one cannot find a convincing naturalistic explanation for some texts? Inevitably, they cannot become a second set labelled “supernatural”, because that possibility isn’t in the matrix you have chosen. So they must instead become a sub-set of “natural” texts labelled “pending explanation.” And they will, without any doubt, remain in that “natural” set permanently, until such time as another possibility matrix is chosen by the people doing the research. The reaction to any dissident who uses such a new matrix will be the accusation that he has invoked a “supernaturalism of the gaps” – whereas they themselves have no gaps, just unfinished business.

And, of course, because every text in their Bible is included either in the main “natural” set or its “pending” subset, they may truthfully say, “We all agree that there is no evidence in the Bible for supernatural events.” And they might add, “But of course, as believers in a God who could easily do miracles, we’d be the first to admit if it was there.” But of course, that can never happen.

The situation in biology, of course, is completely different, because we know it’s a thoroughly natural process…