I’ll leave pngarrison to comment on the interesting paper to which he linked on the last post. Good stuff again – thanks. I’ll just kick off this line of thought with the final sentence of that paper:

We are thus left with a fascinating puzzle as to how an 8-mo-old prelinguistic human not only seems to think of animals as a coherent category but then makes inferences that they alone must have filled insides.

The paper is written from the mindset that this infant concept is somehow the origin of the “folk biology” that animals are integrated wholes, but I would suggest that perhaps the real “folk biology” is more the idea that they aren’t.

One aspect of this “folk biology” is the current popular view, in the ascendant from the beginning of modern science even before evolution, that animals and other living things are machines, or even collections of machines. They are cobbled together by the process of evolution from bits that are more or less independent, the “selfish gene” being one graphic example of this. I’ve looked at that a little recently.

The second aspect is closer to what has piqued my interest for the last few days in particular, which is the widespread influence of what we could call a “folk psychology” of mind-inhabiting-body, “folk” not in the sense of primitive inborn ideas, but in the prevalence of Cartesian dualism in our society. The two are not the same, for “from the beginning it was not so.”

As far as one can tell, primitive societies had a pretty monist anthropology: you don’t keep the bodies of your ancestors in places of honour in your house if you think they have souls separate from their bodies. Certainly Hebrew anthropology, though often misread by western Christians, sees the soul, or nephesh as the living being in toto, and such things as the mind or the heart or the spirit, whilst distinguishable aspects of people, as essentially inseparable aspects of that total life.

Hebrew ideas of humanity remained firmly embodied, which is why the resurrection of the body was the Messianic hope rather than the release of the soul. And yet, given the idea that the dead were somehow still alive in God, there was a loose concept of the “abnormal” separability of the animating spirit at death in Sheol.

This essential unity is reflected in New Testament thinking such as Paul’s idea that one could sin against ones body. Jesus’s hyperbolic teaching on dispensing with ones eye, hand or foot if it causes you to stumble must be understood not as disdain for the body, but as extreme measures to preserve it from sin for eternal life (“lest your whole body be thrown into hell”). I’ll return to that.

Thomist Aristotelian thinking had closely related concepts: the soul was the form of the human being, a “hylomorphic” combination of matter (hyle) and form (morphe) that was nevertheless an inextricable unity. Again some exception was made for the continued existence, in an attenuated form, of the immortal soul until it should be reunited with the body. But the basic unity of the Christian anthropology is historically reflected in the importance of the idea of proper burial, in the power of relics of the saints and so on.

A counter to this came in the influence of Neoplatonic ideas on Christianity, which in extremes like Gnosticism led to a radical dualism in which the body was an enemy to be escaped by the purely spiritual soul. Some such idea (possibly from Augustinian thought) was probably adopted by Descartes as he saw the reasoning “mind” as the immaterial “ghost in the machine”. He divided the world into mind and matter, thus placing the key division not between us-as-beings and the external world, as in Biblical thought, but between “us-as-minds” and the material  world. The result is that our bodies become part of the world outside, rather than simply being “us”. I contend that this “folk psychology”, which is an unconsidered fact at all levels of society, is unrealistic scientifically as well as metaphysically. It has had the tendency to produce, in our culture, a sense of alienation from ourselves, with concomitant effects on the treatment of others.

world. The result is that our bodies become part of the world outside, rather than simply being “us”. I contend that this “folk psychology”, which is an unconsidered fact at all levels of society, is unrealistic scientifically as well as metaphysically. It has had the tendency to produce, in our culture, a sense of alienation from ourselves, with concomitant effects on the treatment of others.

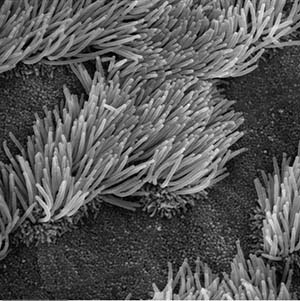

What I mean is this. What infants perceive about the “filled unity” of animals is actually real. Whether or not animals evolved from single celled animals, they certainly develop from a single multi-potent cell. And remarkably (if we trouble to consider it) even by the time that single cell becomes the 37 trillion in our bodies, they all retain a unity of identity and purpose, directed towards the good of the whole.

Not only is it a true physiological commonwealth, but a galaxy of co-operation and even self sacrifice, as our immune cells happily face annihilation from pathogens on our behalf, and planned cell death is a major preserver of overall form and function. This is all the more remarkable the more we realise that the genome is not so much a seat of government as a library of congress. Some unifying idea decides which genes are expressed overall, and in which tissues at which times.

The appearance, at least, is of cells as a community of 37 trillion model citizens all harmoniously dedicated to maintaining the homeostasis of the whole organism. If that doesn’t occasionally fill us with awe, it should, as too should the way that bodies are sometimes capable of acting for higher goods even than their own survival, such as the protection of offspring or the self-sacrifice of those species in which successful reproduction is accompanied by planned death.

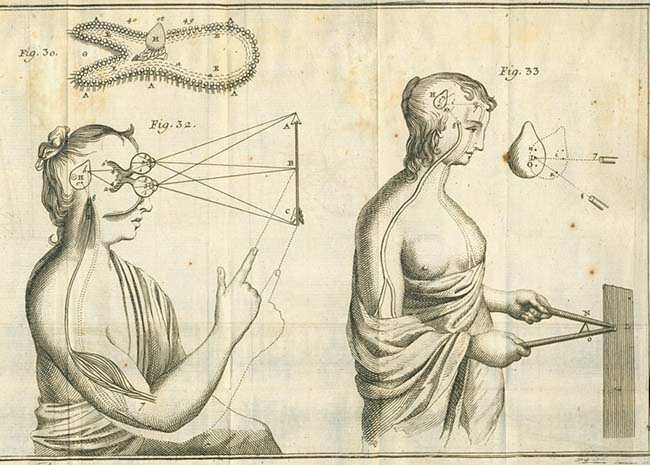

Now, an even more intriguing phenomenon, it seems to me, is how “mind”, in its most general sense, has been developed as a governing principle on an almost completely different level from that ubiquitous physiological self-goverment. Think of even a relatively simple animal negotiating the outside world via its senses and nervous system. The CNS has no idea of the co-operative effort being made on its behalf by the other cells of its body, as it gets on with hunting, avoiding external dangers, competing for mates and so on.

In our own case, even apart from Cartesian ideas, we can take the harmonious operation of our bodies for granted, yet can mostly only appreciate it by investigation rather than introspection. But Cartesian dualism encourages us to forget that, as the body works selflessly on our behalf in its development, it also establishes our mental functions, to whatever degree they are physical, during that development to act selflessly on its behalf.

Primitive people naturally think of “me and thee”. It seems to take a pervading philosophy to think of “me, my body, and thee.” I don’t think it’s an inappropriate analogy to see our higher nervous system as the government appointed by the body to protect it from “threats at home and abroad”. Even theologically that still applies – Paul makes great play in his analogy of the Church as Christ’s body on the fact that nobody harms his own body, but cares for it. When governments start to operate for their own pleasures rather than their people’s good, we call them tyrannies.

Primitive people naturally think of “me and thee”. It seems to take a pervading philosophy to think of “me, my body, and thee.” I don’t think it’s an inappropriate analogy to see our higher nervous system as the government appointed by the body to protect it from “threats at home and abroad”. Even theologically that still applies – Paul makes great play in his analogy of the Church as Christ’s body on the fact that nobody harms his own body, but cares for it. When governments start to operate for their own pleasures rather than their people’s good, we call them tyrannies.

Now, since sin came into the world people have certainly abused their bodies through drunkness, gluttony and so on in all times. But if ones working concept is that mind, will and reason constitute an autonomous “me” separate from ones body, it becomes for the first time logical to say, “It’s my body – I can do as I like with it.” Drug abuse, risk-taking activity and so on make some ethical sense if the mind is seen as the sole focus of what it means to be human. Conversely, of course, it becomes easier to argue that defective minds are expendable as sub-human.

Now, since sin came into the world people have certainly abused their bodies through drunkness, gluttony and so on in all times. But if ones working concept is that mind, will and reason constitute an autonomous “me” separate from ones body, it becomes for the first time logical to say, “It’s my body – I can do as I like with it.” Drug abuse, risk-taking activity and so on make some ethical sense if the mind is seen as the sole focus of what it means to be human. Conversely, of course, it becomes easier to argue that defective minds are expendable as sub-human.

Even the current fashion for celebrities to say they love, and are comfortable with, their body seems to mean moulding it by diets, workouts and surgery to an aesthetic ideal that will attract notice, rather than caring for it as a God-given responsibility.

But to me it all seems a bit like Charles I’s Divine Right of Kings, or Louis XIV starving his people to build Versaille – our bodies, we think, exist for us, “us” being our minds as absolute monarchs. But biologically that isn’t so at all – our minds were created for the good of our bodies; and, of course, for the good of their offspring too, or else we are a house divided against itself. Which isn’t rational at all, but “folk anarchy”, maybe.

I think, in your history narrative, you are placing a simply extraordinary amount of responsibility of Descartes’ shoulders! I am not convinced it is all from him!

From http://www.theistic.net/papers/R.Bolton/article_bolton_dualismandsoul.htm:

Ian

It’s strange that, in researching this post yesterday, for the first time I came across a “Don’t knock Descartes on dualism” article, prompting me to think, yet again, that everything we think we know about the history of ideas is prone to mythicism and subject to revision. I therefore put the origin of your comment down to morphic resonance!

My source said, in essence, that Descartes’ view of things was much more nuanced than his later interpreters suggested, and it is they who are more blameworthy for mind-body dualism. However, I wrongly thought I’d get away with the over-simplification, following as it does the critiques of neo-Aristotelians like Ed Feser, and numerous other commentators on the mind-body problem.

I wasn’t trying to demonize Descartes so much as use him as an established archetype, in the way that Aristotle is usually used as a poster-child for all the science before that time (and was, I believe, by those early moderns trying to reform science).

So maybe Cartesian dualism isn’t so Cartesian – but I still think it has had some unfortunate and widespread effects on the prevalent worldview.

It should be clear that Aquinas is not unambiguously a monist. Rather the opposite. Feser, for example, accepts the name of ‘hylemorphic dualism’ at http://edwardfeser.blogspot.com/2012/09/was-aquinas-dualist.html. That name comes from David Oderberg.

All these people insist that there is something immaterial about the human mind that enables it to, for example, comprehend truths and universals. They see it as essential for operation as a rational being. If so, I would correct for their intellect bias by also insisting that the immaterial part (whatever it is) is also involved with life, love and reception of the transcendent. That practically makes it function like a soul. And it is immaterial.

Hardly a monism, once we get the whole picture.

Ian, I was careful to distinguish hyle(o)morphic dualism in the OP, classing it as compatible with the kind of unity I was suggesting.

Feser writes is his Aquinas:

In other words in my post one must understand the soul (as distinct from the intellect as such) as being the unifying principle whose good each cell serves, and which ought in turn to be served by the mind.

Regarding the soul considered as immortal, Feser writes:

Do you have any view on Near-Death Experiences?

Ian – I don’t have firm views, though I did have a near-death experience at a time when I was too young to know they existed.

FWIW they confirm to me the idea that consciousness is immaterial, but exactly how that relates to the kind of anthropology we’re discussing I’m not sure.

The “propositional content” of NDEs seems to vary enough to make them quite a complex phenomenon rather than a clear window to the spiritual world, which is why I don’t lean to heavily on my own, subjectively significant though it was.

I know a guy who had a NDE after he was injured in car accident, and it was a very significant moment in his life; he experienced God sort of pushing him back into this life and saying, “your time isn’t come yet.” On the other hand, out of body experiences can be experimentally induced. I don’t see any reason that both kinds of accounts can’t be true of the same event.

There seem to sufficiently many occurrences of near-death and out-of-body experiences, not to mention all the visions and angels met in the bible, that the ‘limited operation’ Aquinas allows to the soul apart from the body cannot really be very limited at all.

One thing that has always puzzled me about the oft-cited Greek source of dualism is the very explicit teaching attributed to Jesus to not fear those who can only kill the body, but to fear instead him who can destroy both body and soul in hell. To fault this for its dualism is to accuse Jesus of being overly influenced by Greek thought, or else to question the veracity of what is attributed to him…both problematic responses for those who take scriptures seriously. I’ve asked about this before but don’t remember if anyone was able to give a good answer.

Merv

I think part of the answer is that the terms were all used flexibly rather than technically: the core meaning of soul as “life” overlapped with the concept of “spirit” (though in Genesis 2 matter + spirit (“breath”) -> living soul). The OT at least once uses the (literally) self-contradictory term “dead soul” for a corpse.

Also , no doubt Greek linguistic usage had influenced 1st century Hellenised Palestine, with some muddying of the conceptual waters too.

Yet I don’t think that alters the overall “monism” of Jesus’s teaching – however one distinguishes body and soul, he says they are both in danger of hell apart from the fear of God it’s not a question of discounting the body to preserve the soul.

Thanks, Jon –and fair enough; no — good response, even.

The mind-body-soul unity of scriptural teachings on this that you bring up cannot be doubted. I was just curious how that particular teaching of Jesus fits with it all, and I think you give a plausible mesh.

11/24

It seems a little strange to refer to the mechanistic view of animals/plants as “folk biology.” I would say we are all vitalists unless we learn some science. When I finally took my first biology course as a senior in college I was amazed to find out there were mechanisms at the micro level that could be figured out. Before that of course I knew of things like the heart pumping the blood circulation, but that was just because I had learned about it earlier in school. For millennia intelligent people didn’t figure that out.

I remember a conversation with a friend’s father who was a very conservative Baptist minister. He had taken a biology course at the local junior college and was only encountering the challenge to vitalism when he was in his 50s. Being so conservative in his thinking, his impulse was to resist the mechanistic view. (I not sure what resolution he came to on it – I’m pretty sure he never accepted evolution.) I was excited it by it, because I could see how you could figure things out in molecular biology without being a math genius, and I had found what I wanted to do.

The adequacy of the mechanistic view depends on it accounting for everything we observe. It can certainly account for a lot, but until we have worked out the functions in detail of everything molecular system, we won’t know whether there will something left over. And of course there are those pesky qualia. Some very smart neuroscientists have expected that there will be something left over, and the materialists mock them for that. But the mechanistic view is a collective representation, to use Barfield’s terms, that was only fully formed a few centuries ago, and although it is being acquired at younger ages than when I was a kid, I don’t thinks it’s accurate to call it folk science at this point.

There was an article in Science or Nature back in the 80s or 90s on folk physics. They asked non-scientist adults what would happen in some physical situations to see if their intuitions would fit Newtonian physics. One question was what would path a stone would take if you where swinging it on a string and turned loose. Most people thought the stone would follow the line of the string at the point of release. When I’ve tried the question on my non-science friends, that’s what most of them say. A baseball player can reliably catch a fly ball, but he might not be able to tell you the nature of the curve it was following. Unconscious physical intuition is not the same as conscious analysis of the situation – very often people have physical intuition that works, but their conscious analysis is wrong. Hence the inaccuracies of “folk science.”

Ah folk-medicine:

Antibiotics cure all colds, and a double dose will cure them quicker.

It stands to reason that having a test is good because you can’t be too careful.

Medicine is good, but if you find out it’s a drug you should stop taking it.

pngarrison:

I agree that “folk biology” is not quite accurate as a description of the mechanistic view — though to be fair, Jon put the phrase in “scare quotes” to indicate that he didn’t mean the expression 100% literally. I think his point was that mechanism is the pervasive view of our era’s intelligentsia, and, insofar as the views of the intelligentsia are spread throughout the culture via the school system, popular culture (members of the intelligentsia write the screenplays for Hollywood science fiction films, for example), etc., that mechanism is slowly becoming the “natural” way a modern person thinks about such things.

From your description of yourself, I would guess that you are 10 to 20 years older than I am, and I can confirm that your last paragraph is correct: mechanistic ways of thinking are being acquired at younger ages. Certainly I had a mechanistic rather than a vitalistic understanding of biology at least from early high school on — based on what I was taught in school and read in popular science books. I quite early on perceived that my childhood body/soul dualism was under attack by those who thought of themselves as more educated, and that if I was to be a modern educated person, I was supposed to abandon the idea of a detached soul and regard myself as a bundle of drives, impulses, and neuronic activity that needed material satisfactions such as food and sex (sex being conceived of as a “healthy bodily appetite” devoid of spiritual significance). In the 1970s popular psychology was teaching us that we all needed so many “strokes” per day (compliments paid to us, affirmations that we were doing a good job) to be happy and well-adjusted; so you had bosses going around to employees “stroking” them, not because they had any real human sympathy with them, but because they wanted a happier and more effective workforce. Aldous Huxley certainly called the future correctly.

Similarly, the language of love between parent and child was replaced by the language of “bonding” — you should take your kids to the baseball game because that is good for “parent-child bonding” (the way you should take vitamins because they are good for your bones or skin or eyesight etc.). Of course, the language of “bonding” is the language of glues and adhesives, or of electrons and protons — mechanistic, not humane. No Christian talked that way until the post-WW II immersement of modern people in science and technology, with the social sciences aping the natural sciences, trying to outdo them in reductionism. There has been a general determination by the intelligentsia to “explain away” the specifically human in terms of the subhuman — and not only sociologists and psychologists, but neurologists, biologists and biochemists tend to have strong leanings toward this approach — even when those people are Christians.

The only difference among Christians any more seems to be how far they will allow the reductionism to proceed. Some will allow it to explain animal life, but not man; others will allow it to explain man, but not the origin of life; others will allow it to explain animals, man, and even the origin of life, but will not allow it to explain religious belief, altruism, or free will. The TEs of today are largely among the last-named group. But I think that all such “last-ditch” attempts to hang on to something deemed religiously non-negotiable are doomed to fail, as long as the current conception of natural science — a conception held as tenaciously by Venema and Collins and Falk as by Dawkins and Dennett — is upheld.

TE, in its BioLogos form, is just a delaying action, such as might happen in a military campaign where a general surrenders all his other forts to the enemy and withdraws his entire forces into one big stronghold which he thinks he can hold. In this case, the fort is the NOMA compartment of “ultimate purpose, value and meaning,” and the strategy is for Christian theology to cede all explanation of origins to mechanistic/materialistic natural science, while retaining faith in Jesus, free will, etc. — which, being “metaphysical,” are felt to be secure no matter what science discovers. But that’s delusion. That fort, too (like the “impregnable” fort of Gondor that fell to the forces of Sauron) will fall before the onslaught of a rigorous and unsentimental materialist/mechanist analysis of life and mind — unless the rules of battle are changed. The understanding of “science” that TEs have unthinkingly taken over from Bacon, Descartes, Kant, etc. has to be challenged. Philosophical reconstruction of the entire debate is needed.

“That fort, too (like the “impregnable” fort of Gondor that fell to the forces of Sauron) will fall before the onslaught of a rigorous and unsentimental materialist/mechanist analysis of life and mind.”

I wonder about this. When I was a philosophy student in the ’70s, Gilbert Ryle was de rigueur and I had to slog through The Concept of Mind. I thought it was the most transparent nonsense, and I gather that taking consciousness seriously has made a comeback in both philosophy and neuroscience. When a philosophy is denying or trivializing some basic aspect of human experience, you have to been fairly clever to bamboozle yourself into accepting it, and it can’t be maintained in ordinary experience. The same thing happened to Marxist economics.

The mechanistic view works in ordinary experience – drugs and neurosurgury do what they have been found to do before, but consciousness and the ordinary person’s experience of it stand as an ever present limit to the claim of mechanism to explain everything. I think that will stay the same for many people.

PNG:

I haven’t read Ryle, but Ryle was a philosopher (I suspect not a very good one, but that’s irrelevant here), not a neuroscientist. I’m speaking not of philosophical arguments against free will, etc., but of the arguments that have been put forth by neuroscientists and other empirical workers who have claimed that mind is ultimately an epiphenomenon of brain activity, and that our will, our choices, etc. all ultimately can be — and someday will be — entirely explicable in terms of antecedent conditions of the brain or body.

As a Platonist, I’m of course not *assenting* to such arguments — some of the best work against them, by the way, has been done by an ID proponent, Dr. Michael Egnor, one of America’s leading neurosurgeons — but I’m trying to get you see the exact parallel with the way many TEs argue.

Many TEs seem to be arguing (I say “seem” because often TEs are not very good at expressing themselves on big metaphysical or theological issues, and one sometimes has to fill in the blanks) this: even if evolution from molecules to man could be *completely* explained by *truly random* molecular and genetic events filtered by natural selection, so that no special divine action was necessary at *any* point from the Big Bang onward to produce man, a Christian could still believe that God was in some mysterious way “beyond our understanding” the creator and that the outcomes were what he willed. In such a case “science” would show that evolution was unguided and unplanned — or that any guidance or planning was a completely superfluous explanatory hypothesis for the phenomena, and hence should be discarded by Ockham’s Razor — but “metaphysics” or “faith” would assure us that the actual evolutionary outcomes were somehow brought about by God.

The same could be said about free will: suppose that neuroscience etc. should discover that every decision we make, even every wish, hope, and fear, does not proceed from some imaginary “free” being, a “soul” or “self” inside of us, but from antecedent conditions (neurons, hormones, etc.) of a physical nature; and suppose a scientist could even prove this by *producing*, at will, any hope or fear or decision in any person’s mind by manipulating the brain — make you hate your wife or love paying income tax, make you betray your country or love spinach or enjoy Roger Whittaker songs or Doris Day movies or even (gasp) make you sincerely believe in ID, just by applying the electrodes in the right place — while all along you were convinced that *you* were the one making the free decisions to love, hate, betray, accept ID, etc.

By the above-described TE logic (regarding evolution), all of that still would not prove that we don’t have free will. TEs could just say that on the level of science, there is no free will — or free will is at best a wholly redundant theoretical entity, unneeded to deal with the phenomena — but on the level of metaphysics or theology or faith, there truly is free will — but we can know that only through “the eyes of faith.”

But note that Francis Collins and some other TEs (Hutchinson, if I recall correctly) do not adopt this reasoning. They still hold out for a realm of freedom (moral freedom, religious consciousness of God and Christ, etc.) that determinism cannot touch. They think that material-mechanical explanations are perfectly adequate to explain the body, but not the states of the soul. They think that science will never be able to touch our inner experience. But before Darwin people thought that science would never explain the origin of man, and before Laplace etc. they thought that science would never explain the origin of solar systems. They thought that only God by supernatural action could cause such things. So what gives Francis Collins the confidence that a materialistic/mechanistic explanation of mind, soul, free will, morality, religious belief, etc. isn’t just around the corner? And if one is offered, what will he say then? Will he admit that Christianity is false? Or will he adopt the “TE paradox” approach described above, and say, well, on the scientific level there is no free will, but on the faith level there is?

You see, it’s just a question of what your last non-negotiable is. For YECs, the literal-historical reading of Genesis 1-3 is non-negotiable. For OECs, there is a bit more leeway regarding Genesis, and the age of the earth, and microevolution, but not macroevolution or the creation of man. For ID people, there is leeway on the Bible, and on the age of the earth, and even on macroevolution leading up to man (Behe, Denton), but not regarding the design of life. For TEs, one can give up even design; God can still be the Creator in a meaningful sense even if evolution is driven by truly random mutations and the first cell sprang up by accident in a primordial soup. But while they will surrender even design, some of them, like Collins, draw a line in the sand at free will, morality, the origins of religious belief, etc. They say that science will never be able to touch that. But doesn’t this make TEs just as guilty of “free will of the gaps” as ID folks are of “design of the gaps”?

Of course, I think that all reductionist attempts to eliminate free will, moral conscience, religious sense, etc. will fail on the scientific level. But I differ from TEs in the way I would handle things if the reductionists proved right. I would give up Christian faith entirely; the TEs — or many of them — would just move the goalposts, saying that free will is only knowable with “the eye of faith” because it is on the metaphysical rather than the scientific level, and therefore it doesn’t matter even if the whole world is taken over by programmers who can make anyone believe anything the programmers desire, there is still free will and there can still be real saving knowledge of Christ — outside the reach of science, on the faith plane.

I think that such a move would be gross intellectual cowardice, and if such reductionist science ever becomes a reality, I’ll be leaving the Christian camp and joining Will Provine, etc., and admitting they were right all along, and that I was wrong. I’m not going to hang on to faith by desperate means. A faith that hides out on the metaphysical plane, and thus has no inherent connection with physical reality, is of no interest to me — and it has nothing at all to do with historical Christianity, either.

“If science denies people, the people will soon deny science.” (Yevrag)

pngarrison, I agree with you that truth has a tendency to out. Belief in the mind, like belief in God, will not finally be explained away, whatever the ruling paradigm or even the educational system.

I was chatting yesterday (for the first time) to a neighbour about the general thrust of The Hump. He is an engineer trying to touch base with his “spiritual side” after many years in a materialist mindset. When I mentioned the way science has falsely been made the standard by which all truth is judged, his eyes lit up and he said, “That’s what I’ve been thinking, but never been able to talk about with anyone.”

The problem is that, whilst society gropes towards its inevitable paradigm shift, many casualities will occur as they did under Marxism or any dehumanising and de-spiritualising system. And indeed, a groping society may well fall off a cliff rather than returning to truth.

So warning against a policy of appeasement is still, I my view, appropriate, whilst making arguments for a better worldview.

Ian (we’re all out of nests)

I’m not sure your argumnents work here:

(a) Near death experiences are by definition near the point at which life and intellect depart the body. Both they and death itself are , theologically, exceptional circumstances if death only came through sin. In any case, I’m not sure that out-of-body experiences, even if validated by reading hidden notes etc, require physical separation from the body, but only extended powers of perception.

Do we have evidence that “astral travellers” actually travel? If so, their bodies somehow stay alive whilst they’re gone.

(b) Angels, in Aquinas, are spiritual substances in themselves – they were created non-material, unlike humans who were created from the dust, albeit animated by God’s spirit. And we don’t need Aquinas to know that angels are of heaven, and we’re of earth.

(c) Visions can’t be conclusive – even Paul, presenting his “surpassingly great” experience of heaven as an exceptional evidence of his apostleship, would not commit himself on wheter it was in the body or out of the body.

But my main point is not to say that the soul is not in any way separable from the body, but that the mind is not autonomous of the commonwealth that is our entire being. The spirits at rest in Christ are longing for the resurrection.

I’ve put a paper that describes a relatively simple way to get an out of body sensation at the following page: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/kd8jv6dnayzjsdb/AAAoP4DdeWE-CS_u-1LVtdN7a?dl=0

I haven’t tried it myself, but I would like to. They say it’s an eerie experience. My thinking about so-called NDEs is that if you came back, it wasn’t death. That doesn’t mean that it can’t have spiritual significance for someone. When Joan of Arc was asked if her revelation from God might not just be her imagination, she answered, “how else does God speak to us if not in our imagination?”

I’ve put a paper that describes a relatively simple way to get an out of body sensation at the following page: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/kd8jv6dnayzjsdb/AAAoP4DdeWE-CS_u-1LVtdN7a?dl=0

I haven’t tried it myself, but I would like to. They say it’s an eerie experience. My thinking about so-called NDEs is that if you came back, it wasn’t death. That doesn’t mean that it can’t have spiritual significance for someone. When Joan of Arc was asked if her revelation from God might not just be her imagination, she answered, “how else does God speak to us if not in our imagination?”

The link isn’t working the way I thought. I’ve got to figure this out.

https://www.dropbox.com/s/zmfri1ubtu81mzz/Out%20of%20body%20with%20mirrors.pdf?dl=0

O.k. this should be the link.