An interesting interview with one of those proposing non-Darwinian models of evolution, Luis P Villarreal, on Huffington Post. His virus-centred approach is just another one of many recent advances, but it highlights an aspect that in his estimation has been woefully sidelined in evolutionary studies.

Although the piece is interesting, I’m not too concerned to evaluate the place of his individual research here, but rather what he shares with many of those other workers who, unlike him, are signatories to the Third Way project (now numbering forty-six, including Stephen Talbott, whose work I’ve referenced before). And that is the general conclusion that life cannot be reduced to a collection of simple processes, or in Villarreal’s terms, that it is “non-linear”.

This corresponds to a number of posts of mine, in which I’ve spoken of the fact that increasingly, everything in living organisms is being shown to influence everything else. Reducing it to components, in thought as in deed, makes it disappear. Long ago this was the conviction of Michael Polanyi, and it finds expression in the non-linear dynamics and related mechanisms proposed by those like Stuart Kauffman, Dennis Noble, Stuart Conway Morris and others. But it’s also a conclusion one begins to draw oneself from whatever recent research on control networks, epigenetics and so on that one reads.

Villarreal describes the activity of what he calls the viral “collective”:

It means that sphere of logic is not sufficient to understand this collective. Because if you think about how the collective must operate, in fact, it becomes even a problem of language.

You can always trace a linear link between any two participants or any three or four or five participants in a collective. But if it has a conditional character to it… If you think of alu retroposon RNA in the human brain and it has a particular activity or function and a particular neuron, and it’s doing a specific activity of connecting to some other cell, but then you see in another state, say during learning and memory where it is doing something different and can actually oppose the activity that you saw in the first state – this means an individual entity has multiple activities. And that’s the character of a consortia [sic], which means you now have to start thinking in terms of how the population works and not by just these linear nodes that represent the end reactions. Because they have a conditionality associated with them.

He goes on to say that moving forward in evolutionary science may require not only a paradigm shift in the theory, but in the very way we think about it:

That’s a much more difficult question for me now than you might expect, because it has to do with how we even think and communicate. If living systems work by these processes that are consortial and complex, then our very language and logic is a problem in terms of how we apply it to understand what’s going on. I don’t have a solution.

In a sense our brains are entities adapted to complex thinking. When we think socially, we have this immediate gestalt reaction to a circumstance. All kinds of data are being dealt with, some of it contradictory. We end up with a sense or understanding of what we’re experiencing. But in formal thinking and logic, that’s not how we operate. We use – it’s a system 1 and a system 2 brain, basically.

System 1 behaves by this consortia of information and has both positive and negative, contradictory views that it uses quite comfortably. System 2 behaves linearly and logically.

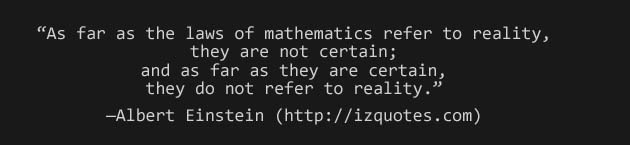

That’s interesting because it restates the ideas I’ve been tossing around here (I think) since I read Polanyi, and that is about the way that science, and indeed all knowledge, depend on the integration of our two quite different kinds of intelligence, which might be called the logical or algorithmic, and the intuitive or imaginative. Positivistic scientism, and related thought-forms with roots in the Enlightenment (and that has included not only scientists but everyone from theologians to ethicists), have restricted “reason” to the first of these, and downplayed the second, to the great damage of society. But like the tunnel-vision so much of the “rationalist” programme, this false dichotomy willfully ignores the vital role of the second in scientific advance, even as it employs it.

In the past I’ve quoted, as an example, Polanyi on Einstein’s intuitive grasp of relativity before he had any evidence or mathematical demonstration whatsoever. But our own GD in a recent comment shows how in the everyday world of science it’s no less true:

…I want to point out one aspect that seems to have been ignored, and that is, a concept is as much a creative process in science, as a musical idea/score is to a musician, or a thought that becomes a painting to an artist.

Now I want to relate this here to theistic science, and how believers conceive of the way the world is, and what its Creator is like. When the early modern scientific programme began, for whatever sociological reasons the idea of “thinking God’s thoughts after him” was closely tied to linear reasoning. For Galileo and many others, mathematics was the language of God. We could understand God’s world because our powers of reasoning were a counterpart to his. This form of reason, as we know, became elevated to more or less divine status in itself as time went by, even replacing God when the skeptical worldview became fashionable. Even now that the wave of rationalism has broken, linear thinking still governs, for most of us, the world of scientific intellect: the imagination tends to be a poor relation that’s the domain of the non-educated, the humanities and, at best, the world of our leisure-time.

There are understandable reasons for this. As far as we can tell from experience, the linear logical mode of thought is more reliable for us, if we follow its disciplines. The imaginative side of reason, however, though it is responsible for the greatest insights like relativity, Kubla Khan or St Matthew’s Passion, can also let people down completely with Scientology, Mein Kampf or astrology. As far as acquiring actual knowledge goes, imagination seems to be the weaker partner, brilliant but wayward and needing to be checked out by linear thought. Behind Villarreal’s words, then, must lurk some degree of fear that we might lack the intuitive capacity necessary ever to comprehend the non-linear nature of life.

There are understandable reasons for this. As far as we can tell from experience, the linear logical mode of thought is more reliable for us, if we follow its disciplines. The imaginative side of reason, however, though it is responsible for the greatest insights like relativity, Kubla Khan or St Matthew’s Passion, can also let people down completely with Scientology, Mein Kampf or astrology. As far as acquiring actual knowledge goes, imagination seems to be the weaker partner, brilliant but wayward and needing to be checked out by linear thought. Behind Villarreal’s words, then, must lurk some degree of fear that we might lack the intuitive capacity necessary ever to comprehend the non-linear nature of life.

It’s worth, though, remembering that for God that is not so, as far as mainstream Christian theology is concerned. Despite the philosophy of early science, in classical theology God’s infinite knowledge is actually more like our sense of intuition. To quote the Reformed systematic theologian, Louis Berkhof:

The knowledge of God may be defined as that perfection of God whereby He, in an entirely unique manner, knows Himself and all things possible and actual in one eternal and most simple act.

This reflects the conclusions from Scripture of the Westminster divines, Aquinas a few centuries earlier and many before that. It relates to the idea of divine simplicity underlying the divine attributes found in Augustine and Anselm. All things come from God, and God knows himself and hence all things not by logical process, but as we (though imperfectly) know ourselves – by direct experience. In that sense one can regard God as being knowledge itself: the idea of God’s being ignorant of something is oxymoronic. In passing one should note that Open Theism, by making God ignorant of the future, has invented a diminished doctrine of God, and arguably made him just a god. Those kenoticists wanting to remain more orthodox retain the classical view but add some version of ignorance through voluntary self-emptying, so that God deliberately ceases to know himself perfectly. Personally I find that disturbing, seeing that I suffer from the same problem and call it “sin”.

But leaving aside the arguments from Scripture and reason, if those like Villarreal are correct about the way life is – that linear thinking is simply incapable of comprehending its “consortial” or “non-linear” processes – then God must needs have an astronomically greater capacity for “gestalt” thinking than we do, since he does understand life, having created it. That’s nice in a way, since it makes his greatest creation consistent with the kind of thought that Scripture and our theology attribute to him. No doubt it would also give some people further cause for complaint that he is cheating us if he makes something we can’t understand, but I’m not aware he ever promised us full comprehension of the world.

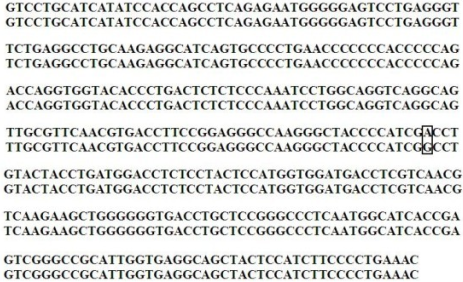

A further thought occurs to me in relation to this, though, and that’s the means through which he may have chosen to create this life. Darwinian evolutionary theory can be seen as a characteristic product of the Age of Reason, which as we saw above was the age of linear reason. Darwinism’s big appeal is its logical simplicity. The dualism of variation and natural selection is about as linear, and as far from gestalt, as one could wish to be – and of course, in those days “reason” wished to be as far from “irrational intuition” as possible. Each variation is essentially independent – just as every chance mutation is in Neodarwinism – and is adjudicated algorithmically by a strictly logical environment. If the variation is beneficial, it survives, and if not, it does not. Continue indefinitely, add up the total, and you have the organism. Until recently, the DNA code gave things an even more literally linear complexion – the environment had its defendant neatly arrayed like beads on a string for judgement.

If, however, what results from evolution can only be understood holistically, one must question how a process that is intrinsically linear could possibly produce it. If it can’t be understood by linear reason, it surely cannot be formed by linear processes. After all, though I write this post letter by letter, it’s only because the creative process involves the background of my holistic thoughts that anything intelligible can result.

If I were to use secondary causes to compose it on my behalf, some intrinsically non-linear natural mechanisms would have to exist. Enter self-organisational theories with all their problems and teleological implications. Or perhaps Michael Behe.