There was a bit of a discussion on BioLogos not long ago about the possibility of miracles in relation to scientific laws. Interesting enough, but the subject has been treated quite frequently, in point of fact, from C S Lewis through to Alvin Plantinga. And it’s not really that controversial amongst contemporary Evangelicals, the target audience. As I pointed out there there’s been an intriguing change in general attitude to miracles within my lifetime, from something no modern man could countenance to something only old-fashioned atheists reject out of hand. But there’s a related field of divine action that’s both more ubiquitous and more controversial than that of occasional miracles.

And that’s daily special providence, and (for the purposes of this piece) especially divine judgement in his ongoing governance of the world. Familiar with this one? “People used to believe that earthquakes, plagues and famines were signs of divine displeasure, but now we know they have natural, scientifically accessible, causes.” Let’s look at how justifiable it is for a Christian to say that.

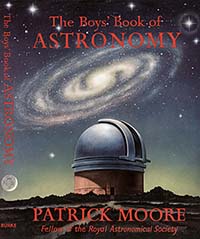

When I was a teenager, I remember having something of an epiphany in my understanding of the Genesis 1 creation account. Up till then, I’d always treated it as a  primitive story matching scientific reality only poorly. In particular I’d baulked (even at the age of eight, or thereabouts) when a Sunday School teacher said God lights the little candles at night. I knew about the nature of stars from The Boy’s Book of Astronomy. As for the Moon, I knew it was a body orbiting earth because of gravity, without its own luminosity and probably captured early in earth’s history. The epiphany was in realising that, for all that, the Moon makes a pretty neat night-light too, so there was in fact no contradiction. But I see I’ve described both these episodes before so I won’t bore you further.

primitive story matching scientific reality only poorly. In particular I’d baulked (even at the age of eight, or thereabouts) when a Sunday School teacher said God lights the little candles at night. I knew about the nature of stars from The Boy’s Book of Astronomy. As for the Moon, I knew it was a body orbiting earth because of gravity, without its own luminosity and probably captured early in earth’s history. The epiphany was in realising that, for all that, the Moon makes a pretty neat night-light too, so there was in fact no contradiction. But I see I’ve described both these episodes before so I won’t bore you further.

But I will dig a bit deeper. Assuming God’s role as Creator, we can easily reason that amongst his final purposes for the Moon, being a light to govern the night was only one, and governing times and seasons for mankind even more secondary. He would also have had in mind the roles that have been identified in generating tides of a certain magnitude, stabilising the tilt of the earth’s rotation, and all those other things required of the Moon to make the world habitable. Likewise, he didn’t have to be taught by human scientists that the Sun is not just the source of light and warmth for us, but the gravitational core of the solar system, around which the planets not only orbit, but arguably even formed.

In other words, the efficient causes identifiable by science regarding the “great lights” may cover any number of divine final causes for them, of which those in Genesis are simply the ones most relevant to the narrative. You can’t exclude God’s intention to stabilise the solar system gravitationally by saying the Bible teaches only about lights and calendars. And you can’t exclude his purpose for lights and calendars by pontificating about Newton’s law of gravity as the “real” scientific cause of things. In fact, you can’t exclude any final purpose whatosever by pointing to any efficient cause whatsoever.

That, of course, is why conjecture about final causation must be severely limited in the scientific enterprise – and also why the scientific enterprise can, by its very nature, tell us so little about what matters most in the universe. But that is not to say that purpose must be denied by scientists – in a general sense, it leaps out at us wherever we examine nature, and of course particularly in the study of living things, which have demonstrable final purposes of their own. Science, in fact, can’t dispense with finality successfully; it just can’t deal with it exhaustively.

I’ve pointed out before how the great co-founder of evolutionary theory, Alfred Russel Wallace, found it impossible to deny final causation after a lifetime of field-naturalism. And he meant multiple final causation at that. The examples he cited included bright and beautiful colouration of species, to which he attributed aesthetic purpose as well as the functional purposes of aposematism, the concept he originated by consideration of natural selection (in reponse to a request from Darwin). Wallace also attributed the different properties of woods to providential provision for mankind’s use, though quite clearly he knew, or could have speculated upon, their adaptive advantages to the relevant tree species.

Final purpose in nature then, and specifically evolution by natural selection, can be affirmed or denied by equally worthy scientists like Wallace and Darwin – you must take your choice between them entirely on non-scientific grounds.

Final purpose in nature then, and specifically evolution by natural selection, can be affirmed or denied by equally worthy scientists like Wallace and Darwin – you must take your choice between them entirely on non-scientific grounds.

Now let me return to that Genesis account of the Sun and Moon from an Evolutionary Creation point of view. Or to be more specific, from a point of view that sees merit in John Walton’s conclusion that the Genesis creation is primarily functional rather than material. We needn’t be doctrinaire here and argue about whether that view excludes material creation from the narrative – I don’t believe even Walton says that. But I’m thinking of those who agree that, since it is not primarily a scientific account, it is inspired and authoritative without having to compete with modern science. It teaches about the functions of creation.

Well, naturally, once one accepts that, one is necessarily accepting that God indeed created the Moon as “the lesser light to govern the night,” quite apart from any role it might have that matches more closesly our scientific priorities. There can be no scientific warrant for denying that the Moon is there to keep us people orientated in the hours of darkness, not to mention to give us a basis for organising our diaries.

But if there is no scientific warrant to use knowledge of the efficient causes of what has been created, in order to deny any particular final cause revealed in Scripture, it follows by the same logic that there is no scientific warrant for using knowledge of any efficient causes operating in nature day by day, to deny that the events are intended by God to serve his particular providential purposes.

To continue with the Moon as an example, for the moment, there is no valid scientific basis to deny that God saw to it that the Moon appeared from behind a cloud at just the moment required so that an escaping refugee would see danger ahead and escape. That is not a statement about any particular mode of divine action, for in practice you could never reduce the circumstances to a simple enough experimental system ever to know whether a miracle occurred contrary to natural laws, the Moon’s appearance was determined materally at the Big Bang, or something concurrentist in between. The point is about the entire separability of final causes from efficient causes.

The same reasoning must be true of another principle that runs throughout Scripture – that God uses things in nature in the judgement and government of the world. He sends drought and famine to Ahab’s kingdom in judgement of their idolatry, and sends rain in reponse to Elijah’s prayer. He sends plague on the Philistines when they dishonour the Ark of the Covenant. He sends a storm to check Jonah’s flight. In New Testament examples Herod Agrippa is struck down and dies from worms for his megalomania, God punishes some in the Corinthian Church with sickness for abusing the Eucharist, and an earthquake overturned the judgement of imprisonment imposed on Paul and Barnabas in Philippi.

Whatever “natural” efficient causes might be found for such occurrences (and like the vast majority of data in the world, they are now irretrievably lost to any possible science), they can have no bearing whasoever on the final causes intended for them by God in his sovereign government of the world. There is therefore no scientific warrant for denying that God routinely acts in judgement in the world, regardless of whether he is held to act retributively or correctively, or both.

That means that to deny such judgements – which are, as I mentioned, unequivocally attributed to God throughout the Bible – can only be done on non-scientific grounds, ie on theological grounds. Though “theological” is really too dignified a word to use for it, when Scripture and the very nature of ethical theism speaks with such a consistent voice. Rather, such denials must be made on the basis of nothing more substantial than personal prejudice. If I don’t like the idea that God judges in such ways, I will deny it and find any and every theological justification for doing so, from the non-judgementalism of Christ (despite Ananias and Sapphira) to the autonomy of nature (despite the calming of the storm).

Anyone is at liberty, I guess, to put forward whatever religious opinion pops into their heads. Only we mustn’t pretend that “science” provides any support whatsoever in the matter.

There’s no question in my mind that God has in the past used natural phenomena in judgement.

I do, however, question the authority of those who make pronouncements about modern day catastrophes as if they knew whether or not they were God’s judgements.

Hi Peter

You’re absolutely right – it’s as invalid as making pronouncements on subtle final purposes as a scientist… unless, of course, you’re a genuine prophet of the Lord. Despite the Charismatic Movement’s lax praxis, though, that last requires a very high standard of validation to avoid being exposed as a false prophet. These Televangelists who instantly connect a tsunami in Japan with immorality in Wisconsin are the worst examples.

I’m here, though, speaking of the theological principle. Just as we can say that we know God created aardvarks even if we have know idea why he did it, we can say that God is behind events, though only with the vaguest idea of what purpose they might serve in his economy.

I’ve been struck just recently at the handle the early Church had on this. In the Didache (possible 1st century), at a time anyway when persecution was rife, it says, “Accept as good whatever experience comes your way, in the knowledge that nothing can happen without God.”

It took them a while to nuance that with necessary talk of “permission” etc, but the initial instinct was correct.

Your rule is good for personal providence, too – and is even more often ignored. Something happens to us, and we can echo what the Didache says. But we’re foolish to say, “God must be using this to teach me that…” He’s using it for something, but may not be telling us what.

Jon wrote (on behalf, I think, of those of us [me] known to think along these lines): ” If I don’t like the idea that God judges in such ways, I will deny it and find any and every theological justification for doing so, from the non-judgementalism of Christ (despite Ananias and Sapphira) to the autonomy of nature (despite the calming of the storm).”

Being the paranoid and somewhat egotistical sort, I easily imagine you had me in mind as you wrote that. And if I play the part (real or imagined), I may as well do so with enthusiasm.

So … in defense of those who do indeed fall foul of your criticism just as it is stated, I think there remains to be explored some defense for those who do indeed dislike “Annanias and Sapphira” style judgmentalism. First, even within your criticism itself you seem to acknowledge the “nonjudgmentalism” of Christ himself which seems to give away the argument. After all, shouldn’t Christ’s “nonjudgmentalism” be a problem for the Annanias and Sapphira character caste rather than vice versa? I know there may be some embedded assumption that the later episode is happening under the direct authority of Christ since the Spirit is attributed a direct hand in their demise. But one can still fairly ask what aspects of God are we to glorify and emulate? Is the notice and praise of the Widow’s mite more reflective of Christ’s Spirit than the smiting of deceitful sinners standing at the altar? I know … those are two different situations as the widow had no thought of making a name for herself. But still, we can note that Jesus reserved his most judgmental attitudes for the religious elite, even calling them children of the devil at times, but without ever deciding they were worthy of immediate death. All in all, those Jesus faced would seem to make the crime of “merely” giving him a smaller portion of your sold lands than you have let on to seem a petty offense. (It’s a good thing Zacchaeus was honest and up front about the half that he [on honor of intent I believe?] gave away — no lightning from heaven there).

But all this is just to work myself into that hard corner, that you so well know. If I am to take all of Scripture as from God (I do), then there the story is, refusing to go away. But if one does not think a story stands well by itself, is it not possible that it is against the backdrop of greater Scriptural admonition that such a discernment can be formed? After all we are willing to set aside genocidal and other atrocities as not representative of the greater message of Scripture about who God is. They are part of it, to be sure, but woefully misrepresentative when they are given main focus. Is it possible there are deeper things hinted at in the New Testament that still wait to be fully understood? The teaching that whatever Christians bind on earth is bound in Heaven, and whatever loosed … seems to hint at an immense power of judgment that is shared with us [or somebody at any rate] for good or for ill. I don’t fully understand that teaching either, but I shudder to think of what sorts of acts we may end up being held accountable for. Not just Ananias, but Peter as well.

On the calming of the storm, that may seem to be a two-edged example as a demonstration of God’s sovereignty. Yes, the winds obey. But that they had to be called to obedience in the first place just begs for the question “so what were they doing just moments before?” The easy answer is that God set it all up just for demonstration purposes. Perhaps. But that doesn’t seem a very satisfying portrait of God’s character either. I do accept fully God’s complete sovereignty over all things so that yes, ultimately, the storm and its calming are all in his hands. But not that I would have drawn that exact conclusion out of this story by itself. The events are related in a way to make it sound as if a gloriously recalcitrant nature can be called back into obedience at the Creator’s pleasure. And it would seem the gospel authors were not overly concerned at painting that very impression. And that alone, if true, ought to merit our curious attention.

Hi Merv

No, I didn’t have you in mind at all, honest! But I can still reply to your enthusiasm, I guess, with zeal.

My reply would be that in picking off individual stories (like Ananias and Sapphira, or the Canaanite occupation) as exceptions one is in danger of missing that greater backdrop, which never loses sight of judgement in conjunction with grace, mercy and forgiveness.

For a start, one is forced to recast Luke’s relaying of the primitive tradition of the Church, that this episode was a salutory sign of Christ’s discipline through the Spirit he gave to the Church, and present it instead as a profound misinterpretation of the whole character of Christ by his apostles and people, who either misunderstood an entirely “natural” (!) coincidence of two sudden deaths as being related to their sin and its exposure; or else as a particularly cruel case of witchdoctoring evil-eye on the part of Peter.

If they got that wrong, then the Pentecost event could equally easily have been mass hysteria, the response to Peter’s first sermon a question of crowd manipulation, and so on. If we don’t trust Scripture’s assertions about God’s will, we can’t trust it as revelation at all (as John Walton explicitly warns in “The Lost World of Scripture”).

My response is not to ask why God would judge such a “trivial” sin so harshly, but why God (and his Church, given the authority by Christ himself to bind on earth, etc) regarded it as not trivial at all. To interpret the Church’s “authority to bind” as some kind of open-ended authority to act unjustly and compel God to accept it pro tem is to put the whole salvation cart before the horse: Jesus’s commission and teaching were to show that the Spirit would give such wisdom that the Church’s considered judgement would reflect, not coerce, the will of heaven. If that weren’t so, it would mean that the Gospel simply repackaged the sin of Eden, when man forged his own wisdom rather than learning it from God.

Whereas Paul admonishes the Corinthians that they are qualified to judge those in the Church now – whereas God judges (present tense) outsiders. He criticises them for failing to exercise that discipline.

If God was displeased with what would amount to a blasphemous attribution of his Name to the death of Ananias and Sapphira, he failed to correct the Jerusalem Church, he failed to get the lesson across to the canonical author, and he failed to instruct the Church for 2 millennia, which took its lead from that Scripture. It’s left, apparently, to this generation to know better about what was really going on – which raises the obvious question of how we got to know Christ so much better than Peter, Paul and the other apostles.

Once the “that’s not really how Christ would act” card is played, it has also to be presented regarding the letters to the seven churches in Revelation, where Jesus himself requires repentance for acts the Lord “hates”, on penalty of closing down the congregations, and of various individual judgements (eg on the person called Jezebel and her followers). It would take forever to enumerate the Bible’s teaching and concrete examples of God’s judging here and now (and in the future, finally), because it’s so ubiquitous. I offer the whole Bible as my evidence!

Jesus did not judge (apart from fig trees, demons, money-changers and storms, perhaps) because as he clearly said he came in the flesh to save, not to judge. But, on the consistent evidence of Scripture “We believe he will come to judge the quick and the dead”. But all power and authority has already been given to him by the Father, which is why the Great Commission is his project rather than ours, and why Acts presents everything from Roman injustice to violent storms at sea as his tools in that work.

In Heb 12.4ff we are urged to struggle against sin, with the possibility of “shedding blood” implying that that struggle includes persecution. He then categorizes that whole complex as “the Lord’s discipline” (lit “scourging”) of those he loves. 1 Pet 4.17ff too speaks of not be ashamed of suffering for Christ, but then, to our surprise, describes it in terms of judgement beginning “now” with the household of God (with dire implications for those outside).

As for the calming of the storm, it doesn’t really affect the case about God’s using of natural phenomena for his purposes, including judgement. The Genesis creation account is largely about the subordination of disorder to his good purposes. Even if we grant some idea of chaos within nature, it is no less subject to his will than the acts of evil men, which are explicitly stated to be in God’s hands in many places in Scripture.

But we also read that “He makes the clouds his chariot and rides on the wings of the wind,” and that “He causes the clouds to rise over the whole earth. He sends the lightning with the rain and releases the wind from his storehouses.” There is no implication of setting things up for demonstration purposes – but there is a deep mystery implicit regarding God’s actions, which no attempt is made to defuse.

Once more that raises the issue I mentioned in my comment to Peter, that of “permission” v “volition.” I didn’t raise that in the OP as it is a nuance not necessary to my case. The Didache was able to advise us to receive all circumstances as blessings, as “all things are from God”. I believe (but haven’t checked) that it was Clement of Alexandria a century or two later who began to examine how Roman persecution could be a heinous evil and yet come within the providence of the good God. The overall point is that he concluded it did come within providence (by the agency of permissive will), rather than that the Church was wrong to believe that all events ultimately come from God and serve his purposes.

Hi Jon,

Interesting approach – I am inclined to treat any miracle with great skepticism and unless it was my personal experience, I would regard any claims of miracles awaiting confirmation by the Church. This is underscored by so many odd statements made by a wide variety of persons who, often, display odd outlooks regarding faith.

On the broader question, miracles discussed in the Gospels are inevitably linked to faith by the recipient, and Christ acknowledging such faith. There are instances where the disciples could not perform miracles and Christ explained this again in terms of faith. Again, compassion by Christ and faith from the sufferer are central to such unusual events.

Providence and judgement by God are expressions of that faith. Dealing with evil in this world is part of the Christian calling, to provide light to the darkness and to keep the faith against all that seeks to destroy it. It is for this (keeping and strengthening faith) that the Church has believed that all things work for the good of those who believe and put their trust in Christ.

I am struck by instances in the Gospels where Christ tried to get away from crowds, does not look for a chance to perform miracles, and kept warning against looking for signs (miracles as Jews saw them).

Hi GD

On miracles, if we put to one side our age’s materialist prejudices, I wonder how often miracles ought to happen in the world? There doesn’t seem to be a rule one could invoke, though they seem uncommon enough to be noticeably related to certain unique ministries in the Bible.

A watertight definition of “miracle” would help, and I’m not sure there is one. The example I mentioned recently of the Jordan piling up at Adam – a repeatedly observed natural phenomenon – was still a miracle when it coincided with Israel’s needing to cross. Biblically, “miracle” seems to have more to do with significance than with modus operandi.

Nevertheless, I encountered a smattering of inexplicable healings related to prayer/Christian ministry in my medical career. Arguably one might use the word “miracle” for such things, but my working model was rather that God gives his children good gifts as tokens of the age to come – the termininology and theories of divine action aren’t particularly relevant to living in that reality.

I remember one instance in particular (in a friend, as it happened) in which the cardiologist was astonished that a repeat angiogram, done because the disappearance of his severe angina put the imminent surgery into question, showed that the coronary arteries had cleared. The (non-Christian) consultant was pleased the patient was better, watched like a hawk over a couple of years in case of relapse, mentioned the patient’s having attributed his cure to prayer, and shrugged. What else could he do, scientifically? It was an anomalous instance, confirmed by clinical evidence, but not amenable to any repeatable research.

Providence, though, was my subject here – a deliberate attempt on my part to get away from thinking about “exceptional miracles” to consider “routine government of the world.”

I agree that only faith can perceive events as being governed by God, but that’s a truism, isn’t it? My point is that science has even less to say on the matter than on miracles.

Hi Jon,

Yes miracles as such are personal and few others can decide – on providence however, we inevitably end up speaking of Sovereignty, omnipotence, and similar attributes of God, and we end up with Theodicy. My point has more to do with God ensuring our faith is strengthened within a world of events which at times, would not make sense to me (e.g. suffering of innocents). It is a difficult area to negotiate without a sense of hope and faith for a Christian (and for an atheist, a reliance on chance, happenstance, and such).

So I guess my interest in this post from you is to ask why science gets into this subject?

GD

Answering the last question first – I think it was Enlightenment thinking, invoking the “laws of science”, that made belief in special providence seem implausible not only to atheists, but to many Christians. Despite the eclipse of Enlightenment rationalism, I felt that the negative conclusion on Providence has become ingrained and unquestioned for many, so was worth challenging here by showing that science doesn’t have anything useful to say on the subject.

My thought process began, I think, with being struck by the “all things are from God” teaching that appears really early on in the post-apostolic era… and by finding the same thing as a central theme in the Revelation of John, which I’m teaching to a group at present.

That ties in very closely with your main para, because at a time when severe persecution was a very present reality, they took their comfort not primarily from any idea that God would eventually redress their injustices, but from the knowledge that God’s purposes both for them and his kingdom lay behind them, and so they could and should be regarded as blessings from his hand.

Needless to say a belief in “chance and happenstance” gives none of the same assurance – and it does indeed gain a foothold with Christians as well as unbelievers.

Generally a lot has changed in the way we as a population in the West think, and the Enlightenment, science, and modernity are all ways of finding a cause for such changes. I would add to the list, a change related to what we would now regard as superstition, an outlook that mixed up many beliefs on miracles, holy relics, spiritual powers, and other stuff that had its origins in pagan beliefs. Science than becomes the ‘liberator’ from such things, which ironically amounts to replacing one superstition with another.

Getting back to current thinking of Christians, I suspect the notion of suffering in nature as either caused by God, or at least why God would allow it, may be a big problem when discussing Providence. My feeling is nowadays people are uncomfortable with equating sin with suffering, and especially when we need to see the universal nature of sin (as all of us have sinned).

The other aspect I think is the thought that God is working – I have pondered the Sabbath and God resting, and find this very interesting. John 5:17 (and other passages where Jesus worked on the Sabbath to heal, and was moved by people’s suffering) provide food for thought.

GD

Your penultimate paragraph – it’s equally instructive to wonder why before “nowadays” this wasn’t an issue that seemed to trouble a couple of millennia of Christian thinkers at all, though they were totally aware of it.

Jon wrote: “My reply would be that in picking off individual stories (like Ananias and Sapphira, or the Canaanite occupation) as exceptions one is in danger of missing that greater backdrop, which never loses sight of judgement in conjunction with grace, mercy and forgiveness.”

This morning I read this passage in Hebrews: “For if we willfully continue to sin after we have received the knowledge of the truth, there no longer remains a sacrifice for sins, but a fearful expectation of judgment and fiery indignation, which will devour the adversaries.” and a few verses later … “For we know Him who said, ‘vengeance is Mine,’ says the Lord, ‘I will repay.’ And again He says, ‘The Lord will judge His people.’ It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God.”

The last sentence of yours in the paragraph I quoted above, speaking of the conjunction, puts it well I think. Scriptures certainly do overflow with the goodness and righteousness of God’s judgments, as well as his loving kindness and mercy.

Merv

There’s a whole strand of “classical theism” that teaches that all God’s attributes are aspects of his essentially simple nature: that is (in this context) his love and his judgement are the same things viewed from different directions.

Humanly speaking something of that kind is true anyway – the punishment of persecutors is at the same moment the vindication of the persecuted. God’s long-withheld judgement on the Amorites (Gen 15.16) was also the fulfilment of the promise of a homeland to Abraham.

I would not want to speculate presumptuously on how that relates to final judgement, but it’s interesting that Revelation represents the redeemed as glorifying God for his salvation, glory and power in the destruction of “Babylon”, and rejoicing in the fulfilment of his reign thereby.

Perhaps that all speaks to the OP’s theme of God’s present providences – the anguish and injustice of persecution at the hands of wicked men is not only compatible with God’s blessing, but even mediates it through salvific chastisement, and through the opportunity to emulate Christ’s testimony and sufferings.

Perhaps we don’t appreciate that now because our own acts and motives are usually so incoherent. For us, our most generous works are tempered with pride or whatever, and love disappears whenever we judge others. That God might cause/willingly permit suffering, somehow, because of his love makes no sense to us.

And that’s before we come to ask why any particular event would be right in God’s eyes, when in our eyes it isn’t… which, being interpreted, often means “Shall not I, the earthly judge of all, including God, do right?”