We left the last blog post with a simple “toolkit” from Genesis 1 which, whilst it may not “define” man in the way Aquinas sought to do, certainly describes him theologically in a way that enables us to interrogate the archaeological record for biblically human origins.

This toolkit consisted of:

- Signs of rule over the world (plurality and communal effort being one indicator), and particularly over the other creatures.

- Signs of mind/language (in turn implying self-awareness and will), primarily preserved through creatively-fashioned

artifacts.

It’s not hard to apply those to the modern world of information and high technology, a world of 7 billion humans in which we fool ourselves that we alone govern the world and can destroy it or save it. A better way to apply the toolkit in the present is to some isolated hunter-gather tribe. However much such a community may seem to “live in harmony” with nature, in fact wherever he lives man is, most unexpectedly from his weak physical endowments, an apex predator. Even when he does not tame animals for labour, not only will he exploit the largest and best-armed herbivores for food, but will take out top-level predators that endanger his own livelihood.

Linguists tell us that there is no such thing as a primitive human language. All have comparable deep structures, and all can therefore express anything the others can, whilst of course one recognises that limitations of understanding and vocabulary may make an Andaman islander’s description of a computer sub-optimal – just as would be a description of Andaman religion by an English software designer. An adopted Andaman baby could quite possibly end up as a software engineer: the cultural differences are just that – cultural, not evolutionary nor racial. And the most primitive human languages are used to express symbolic and religious ideas.

In passing, let’s note that the established differences in IQ between the various broad-brush races, even if real, are in the scheme of things trivial, even though sociologically significant. The fact that genetically identifiable sub-groups might exhibit slightly different, though mainly overlapping, distributions of IQ, physical strength, height or skull size gives us no reason to doubt they are all “children of Adam.” This is important to note because nineteenth century evolutionists like Haeckel stupidly considered the gap between Europeans and Australian aborigines to be greater than that between the latter and the great apes. He failed to appreciate… well, most things, but primarily that technological achievement is not the only measure of human culture. As I quoted Don Richardson in my Generations:

Each society or group of societies had its own starting line, its own starting time, its own course, and its own finish line. . . . A culture pursuing harmony with nature, for example, should not be judged by the norms of a culture pursuing technological mastery over nature!

This truth is demonstrated sharply as similar evolutionary assumptions about our “primitive” hominin forbears have been progressively stripped away. During my education, much was made of the smaller cranial capacity of Neanderthals, and they were always illustrated as stooping skin-draped savages (naked savages wouldn’t have been acceptable in school books!). Even my old 1974 Stonehenge guidebook illustrates Neolithic people, actually highly refined, in similar shaggy animal skins, with unkempt hair. But now we know that the average Neanderthal cranial capacity was greater than ours, and that indeed the earliest H. sapiens also had a larger brain, on average, than us. Even Homo erectus had a brain size within the distribution of modern humans, making its smaller average size of questionable significance.

Likewise, the frequent dating of “symbolic thought” to the later Palaeolithic has had to be revised as more ancient evidence has come to light. If we’re not constrained by evolutionary thinking, we see that much of the paucity of cultural evidence early in human history is due to the depradations of time on artifacts, and the possibility of most creativity being expressed in perishable materials, or even in ritual and verbal activity, rather than in stones. Sometimes, only new technology has detected what was missed before. But additionally it is clear that lack of a technology or particular artistic techniques has no bearing on intelligence, or we’d conclude that James Watt was less evolved than the average Facebook addict.

For example, when one anthropologist commented on the lack of development in Acheulian stone tools for a million years during the time of H. erectus he said is was a time of “almost unimaginable monotony.” But Australian aboriginal tools have not changed much over the last 40,000 years, and I doubt during that time that boredom has been a problem for humans just as intelligent as Europeans. They have just chosen to channel their energies differently. Perhaps they discovered long ago that “If it ain’t bust, don’t fix it.” And if woodworking was advancing in leaps and bounds whilst stone technology was static, how would we know from archaeology?

And that brings me back to H. erectus, because significant levels of creative activity and biological dominance have now been found in the type that is, essentially, the wellspring of the genus Homo, dating back a couple of million years. You may have heard of the savage controversies within the field of human anthropology. The “lumpers” in essence recognise only H. erectus, H. neanderthalis, and H. sapiens, with some minor variants. A few even consider all three to be varieties of a single species, and that is not unreasonable given the discovery over the last few years of extensive, and successful, interbreeding between them.

The “splitters” recognise far more human species, and it does not take long to realise that a strong motive for this is in order to accommodate Darwinian gradualism into human history. But it is fairly widely recognised that there is a massive gulf between our supposed evolutionary ancestors, the Australopithecines, and every well-documented variety of Homo. To cut a long story short, like virtually every other example I’ve ever looked at in evolutionary history, the appearance of mankind on the scene was, to all appearances of the evidence, saltational. And the earliest well-represented type is H. erectus, so I’ll look at that type first. If we find theological signs of humanity there, then everything downstream is “in the image and likeness of God” too.

An overview of erectus culture like this shows that they did most of the things we’d expect to see in a hunter gatherer culture today. They hunted the megafauna of their time, and from later times we have evidence for hunting of birds and fish, and that shows that, apparently from the start, they were apex predators. It seems to me that the suggestion they were at first scavengers is more a requirement of belief in their evolutionary rise than from the evidence. There is evidence of co-operative planning in their hunts, as there is in the building of houses up to 49 feet long – surely communal longhouses. A paved 27 foot circle “for cultural activities” seems to suggest dancing, or ritual, but is once more a community undertaking with some shared purpose in mind.

All of these appear to require language, regardless of the speculations in the linked article on the small size of frontal lobes, vertebral foramina and so on. At one stage the lack of a hyoid bone was also thought to preclude language – until better fossils showed it was present. It seems that had no function but enabled speech, or that it was for the purpose of speech.

Another article, on linguistics, identifies three “levels” of linguistic complexity, all of which are present in all known languages. It speculates that erectus possessed (initially) only the arbitrarily-determined lowest level of language, but this is entirely based on the assumption that language evolved. But if anything the older and more primitive human languages are, the more the use of symbolism and metaphor is seen. On that basis imagination might have been a core feature of language from the start. And, like DNA, it is hard to imagine speech, and thought, evolving in stages. Neither are merely cultural phenomena.

I have already suggested that the million-year long career of the Acheulian axe could denote cultural stability, rather than mental stasis. Nevertheless, the picture I included in the first article of this series, of a Homo heidelbergenis (which some see as a subspecies of erectus) teaching his child to make them, suggests how necessary language might be to such a long technological tradition. Acheulian axe production was deeply goal-orientated, compared to the smashed rock tools attributed to Australopithecus. They required knapping to a standard shape, and then a second stage of retouching. They were sometimes retouched after use. As one researcher put it, the maker has to “see” the final product within the core, as a modern sculptor does, together of course with its functional purpose.

Imagine trying to train up your son in the toolmaking skill without language. In any case, as I wrote in the last episode, it is doubtful if even the internal process of planning could exist without language – and symbolic language at that. The same is true of the astonishingly preserved Schöningen spears, up to 400K years old. These have been reproduced and found to be made from chosen woods, and carefully straightened and balanced for throwing. They are nearly identical to spears used by hunter-gatherer tribes today, so are presumably good at what they do. But like a crafted stone axe, the rising generations needs to be taught the manufacturing tradition, using speech: “Not like that, you muggins – it has to balance here or it won’t hit the horse.”

I doubt, too, that the incised shell illustrated in the linked overview article would exist without both aesthetic and symbolic purposes underlying its production – much like the paved ground mentioned earlier. Even more clear is the creative sense behind the Acheulian axe illustrating Part 2 of this series, formed round a fossil shell. It seems my source was wrong in ageing it at 1.6 million years – it’s apparently a mere 1/4 million years, and an all-British design. But it’s still manufactured either by heidelbergensis or erectus, if there is a real difference, and the lack of wear tempts one to see it as more ceremonial than functional.

Homo erectus seems to have invented clothing too. Genetics estimates that the human body-louse, dependent on clothing, evolved around 200K years ago, well into the erectus era. I’m rather distrustful of the accuracy of “molecular clock” estimates, but if accurate, even before that time, when erectus was restricted to warm climes, the minimal clothing seen in tropical tribes now could still have existed, without harbouring body-lice. As an old comic song says, to the tune of Men of Harlech:

Saxons, you can save your stitches

Sewing coats for bugs in breeches

We have woad to clothe us, which is

Not a nest for fleas.

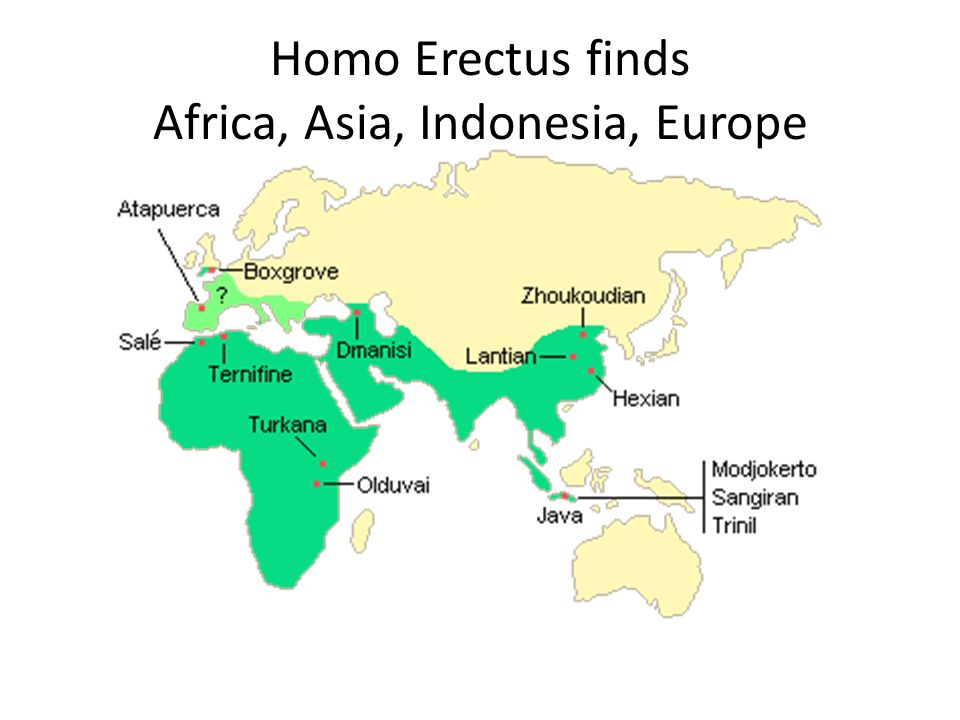

Lastly in this all-too brief exploration, consider the geographical distribution of H. erectus compared to its supposed immediate precursor, Australopithecus. Here’s the known distribution of the whole genus of the latter:

For the most part it seems to wander up and down the Rift Valley for millions of years. Compare it with the single species of Homo erectus (including heidelbergensis in lighter green).

It’s as if they were taking God’s creation ordinance to “fill the earth” seriously. They even used boats or rafts of some sort to occupy islands. This suggests intentional migration as well as technological skill, rather than, say, “following the herds” from season to season.

I’m very doubtful about the plausibility of the suggestions that Homo erectus evolved radically greater intelligence as it went along. I know of no comparable example of a species changing fundamentally during its existence – the palaeontological pattern is nearly always of sudden emergence, stasis, and eventual extinction. That appears to be the pattern here, though interbreeding with similarly intelligent variants appears to have been its final fate. More likely, it appears to me, Homo erectus appeared fully-equipped for human life, either saltationally from an Australopithecine (for which no scientific explanation exists), or by divine act either transforming said Autralopithecine, or de novo.

I would add that however it happened, Genesis seems to suggest it was by the same creative route followed for all the other animals on Day 6 of the account, whose mapping to nature is not described. In other words, we need not necessarily look for an earlier single couple than Adam and Eve, unless we also choose to believe that all species began from a single pair. The fact that Buggs and Swamidass showed an ancient human bottleneck to be biologically possible does not make it theologically necessary, unless you wish to place the fall of man a couple of million years ago.

In summary, then, the picture I conclude is that mankind “in God’s image” pre-existed Adam and Eve by a couple of million years, acting the role of “people from the earth” quite successfully and according to God’s creation ordinance. This conclusion, which seems to make most sense of the archaeology, only appears to make theological sense in the context of the Genealogical Adam and Eve, in which a special representative of mankind is chosen for a particular role as divine covenant-mediator, to bring humanity into a new, spiritual existence.

That spiritual existence is, in fact, the new heavens and new earth that forms the Scriptural hope of a transformed cosmos, and that is far beyond what the natural earthly creation ever had to offer, even before the Fall. But that’s not to count early man as insignificant in God’s eyes. He did a good job subduing the earth and filling it for a couple of million years, before Adam messed it up in a single generation.