Writing my piece on Bede reminded me that if he can be decribed as a “scientist”, he’s an outlier – though a legitimate one – in the process by which modern science came to be established. There’s beginning to be a good body of literature supporting the even greater body of evidence that natural philosophy developed in the wake of the Christian doctrine of creation, and entails it. This can be found both in older books like that of Stanley Jaki and newer ones like James Hannam’s. In fact an essay of Hannam’s on his website includes my starting point here.

One can glean from such sources that the biblical doctrine of creation overturned some prevalent pagan and philosophical ideas that militated against the investigation of nature. The first was the idea that nature was chaotic – a disconnected series of largely hostile “things” ruled, if at all, by fate and the arbitrary decisions of the gods (who suffered by fate as well). You wouldn’t find much of interest, then, in investigating such a world (and it would have been literally tempting fate).

The second thing was the concept of order that did find its way into classical thought, which was the perfect order of reason, demonstrated in the heavens, whose motions found an imperfect reflection in the destiny of the world below, in whose events they were, of course, astrologically involved. The heavens, then, moved in perfect circles – apprehended, if you were a Pythagorean, through geometry (though you never experienced its perfection with your actual ruler and compass) and music.

Platonic forms too were perfect, so your head ought to be completely spherical, if it hadn’t been cobbled together by the Demiurge who had his plans upside down. The result was that you were more likely to find reality by perfecting your reason and deciding what ought to be, rather than poking around the dirty world – which was, in any case, was slaves’ work beneath the dignity of a high-status philosopher.

Jaki’s book majors on the related idea of the Great Year, when every heavenly body periodically lines up as at the beginning. At that point everything in the cosmos is destroyed before following exactly the same course again – including you, me and the philosophers, all undergoing a cosmic Groundhog Day throughout the eternal existence of the universe. It’s not unlike some older versions of the big-bang, big-crunch theory where the main event is the periodic reversal of the arrow of time – and that’s not surprising because it follows the same philosophical presuppositions of an eternal and purposeless cosmos. But given that all events are just recurring reflections of the planetary motions, scientific investigation is rather pointless. Nothing will change it – even true love.

The Great Year, incidentally, was a popular idea recovered at the start of the Renaissance, which helped retard the progress of science until a later generation, espousing Christian creation doctrine, rejected it. Giordano Bruno was of the first type, not the second.

Christianity cut through all that with the doctrine that at the head of all things was one rational, loving God. He made the Universe as a creative rational act, and us as creatures reflecting his rationality and so able to appreciate what he has done in creation. Indeed it was not only a joy, but a duty to investigate the world he made for us. The logic of creation doctrine includes at least three elements:

(1) A God of love, reason and order would endue his creation with order too, as both Scripture and even superficial experience showed. So far, so Pythagorean (and indeed a believing scientist like Kepler was heavily influenced by the Pythagorean concept of heavenly order). And so science was, in part, a quest to find the orderly patterns that came to be called scientific laws.

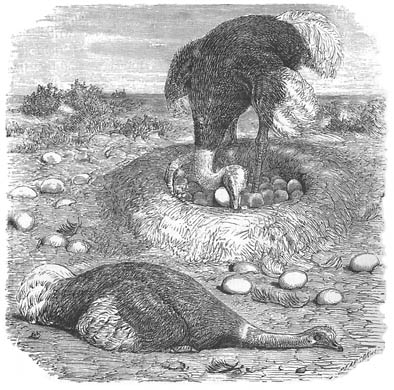

(2) But unlike the Greeks, Christians realised that the order of the cosmos was not a necessary order – the only way that the perfection of reason could mainfest itself in Greek thought – but contingent. God, in his holiness, was not capricious or arbitrary, but he was free to make whatever he liked, not bound to make what suited mathematical perfection. Heads are not spherical, because God preferred to make them as they are. Much of what he made is mysterious – even dangerous or deadly. But as Job taught, God rejoiced in those very things – the ostrich has a life demonstrating God’s wisdom – but somehow shown through its stupidity and carelessness. The crocodile and hippo have a motley selection of armaments and lethally unfriendly temperaments, but they have a place in God’s joyful creativity because he chose that they should. Much of creation, then, was surprising, but all was good – the only way one was going to begin to understand it, though, was by investigating what is there, rather than reasoning about what ought to be there.

(3) Briefly, the third thing is that time, and events, are not cyclical but moving unidirectionally towards the purpose God has set for the end of time. All things therefore have purposes within that great purpose, which might be worth investigating in themselves for God’s glory, but equally (as per Francis Bacon) might be harnessed for human utility.

And so we have in place the bones of a scientific programme, and it depends on Christian teachings and, therefore, ultimately on the existence of the Christian God, or one very like him. Who else will make the patterns of law, who govern the contingency, and who create time and final causes? And who endow humans with reliable reason and sufficient powers to perceive what is in nature?

And so we can see the emphasis on order in the work of someone like Newton. We can, however, see the emphasis on contingency in Linnaeus’ classification of living species, which form, as it were, the same kind of intelligent, broken patterns that make up great art.

At this point let me draw attention to the fact that this is the very opposite of a design apologetic, worthwhile though that might be in an age that has largely returned to the science-stopping old ideas of materialistic purposelessness. Rather, because God is who he is, we know nature is what it is, and we know that we too possess godlike rationality to think God’s thoughts after him, to his greater glory. It is, as an increasing number of thinkers are starting to realise, a far more coherent system of justification for science than materialism could ever be. And, in passing, it is what the Classical Providential Naturalism of The Hump is about.

My main concern today is to focus in on the “contingent” aspect of creation which, remember, has to be directly investigated because God could have done things any number of other ways. Early science of this type has been compared to art criticism, which is not unfair, but probably downplays how scientific it can be. Linnaeus’s classification, for example, demonstrates in detail a contingent order, whether seen as it was intended, a demonstration of God’s thought-patterns, or as it is used now, to suggest evolutionary relatedness.

Contingency, in that context, is about God’s freedom do make what he likes, not (as the word is more often used now) about chance. “Contingency” is simply the opposite of “necessity”. To early Christian scientists, it would of course include chance, but always under God’s governing providence. And though they had no mathematical statistics, they understood something of random contingency – a tree can fall any way (though more often away from the prevailing wind): the fact that a dice is fair entails that the numbers turn up equally often (though God or the devil may well determine who wins).

Contingency also covered “reasons unknown”. And the more out of the ordinary the event, and the more purposeful, the more likely it was to be attributed to God’s freedom than to chance. For example, in my post on Bede I mentioned his recording the local variations in tides, unexplained by the orderly pattern of lunar attraction he had found. I don’t think he suggests any hypotheses about these, but we can be pretty certain he would (a) not attribute them to chance, because there was obviously some kind of pattern involved, albeit too complex to understand and (b) would not attribute them to divine intervention or “contingent” creation, since there appeared no particular function for them. So my guess is that he would believe some other natural cause or causes would explain them, could they be found.

On the other hand, in his Ecclesiastical History he lists a number of miracles, including one from his own circle in which someone falling from scaffolding was healed through prayer. This is a rare (in fact, generally unknown) event, with the clear function of restoring life and health. God’s hand in it is clear. Miracles are one thing, but my point is to show that this worldview saw all things as God’s work, but kept apart those which resulted from natural patterns like the mysterious dragging effect of the Moon on the tides, and those which resulted from God’s free choices. The distinction is basically that between different aspects of God’s nature – “law” shows his reason and immutability, and “contingency” his sovereign freedom. These two things arise from the Doctrine of Creation, as applied to the broadly scientific enterprise, and both are essential to it.

It would be detrimental to that doctrine to subsume one to the other, for example by suggesting that there was a hidden law of nature responsible for all the contingency we see around. That would imply that the divine contingency is illusory, merely being a law-like outcome that might recur come the next Great Year. The whole point of such contingency is that is demonstrates God’s independence of natural law.

It would be equally derogatory to God’s creation to put contingency down to chance, for that too would be more like the old Greek idea of an eternal universe of atoms colliding randomly than the freedom of God to express his holiness and will through particularity.

I suggest, then, that the kind of theistic evolution that reduces evolution to a process that plays out from basic laws would not appeal to those who began the scientific enterprise. There’s order in it, indeed, but it’s too Pythagorean to leave much room for God’s creative liberty.

I’ve mentioned Simon Conway Morris’s convergent evolution recently, and its support from such TEs. It says, in essence, that the universe is set up in such a lawlike way that, whichever route evolution travels, it will end up in more or less the same places. A Linnaeus would see in that the denial of his whole purpose in study – the planned, abundant, diversity of God’s creative genius.

For in convergent evolution, and in Evolutionary Creation as it seems to play out (in the absence of clarification from those who hold it), the laws underpin the order, and the contingency is always the contingency of chance, and never the contingency of choice (for which it leaves no mechanism and admits no likelihood of observation).

The plausibility, or otherwise, of this is the province of ID: do the facts suggest the high probabilities of chance, or the low, but ordered, probabilities of choice? But it is the same kind of ID practised unconsciously by those like Bede, distinguishing common-or-garden chance from purposeful organisation. One might use a coin toss to decide who starts a foorball match – but one would not use a lightning strike. God may use brownian motion to assemble a biological structure, but probably not the energy from a fire-whirl or the grinding of hens’ teeth.

Whatever the plausibility of entirely law-based evolution, however, the theology of it seems to me to lose an entire half of the original Christian scientific impetus – that we examine the world not just to find God’s laws, but to discover his free choices. The default position for investigating organised and functional contingency is “choice”, not “chance.”

Well, I’ve been trying to catch up on your latest essays here, Jon, and am just back from a week away but now needing to get back to work. But quickly here and now (and with more chewing needed than my quick reading allowed on this last installment) I will just say that I really appreciate your discussion of St. Bede. And I’ll have to see if I can find a copy of Douthat’s diagnosis of our heresies this side of the puddle. My summer reading possibilities are getting more interesting thanks to you.

And to think you could have been condemned to lounging by the pool with some escapist novel…

In case you missed the link have a look at some of Arthur Jones’ stuff on Christian education, referenced from the “Science in Schools UK” thread. Well thought through.

Arthur Jones’ chapter “Part III: Overview of the Sciences” is imo one of the best treatments of the subject for non-specialists and educators. The acrimonious debates by materialists and often theist evolutionists/ID/others are made irrational because, too often, the matters discussed in this chapter are either ignored, or some people are simply ignorant of the areas in which ‘the facts of science’ are central to the discussion.

I agree GD. I think it might have been Arthur, way back in the eighties, who first got me thinking about worldviews at all.

I have a personal interest in all this. My son studied biology at A-level. Set reading: “Blind Watchmaker” – a science book. His biology teacher was actually, by coincidence, a committed Christian, but was also committed to being “professional” and leaving his faith at the door of the classroom. So the underlying metaphysics of the book was never discussed: it was “scientific” and so by default “neutral” and “true”, as we all know from Dawkins’ subsequent writing.

As it happens my son also did religious studies (as it was an easy option!). Certainly, materialism and worldviews were never discussed. Instead, comparative religion was, because that can be taught in a neutral manner – and being professional, the RE teachers left their own convictions at the classroom door (if they had any), and taught religion in the “view from nowhere” way that, of course, communicated that no particular god matters.

As I wrote at the time, “‘No Position’ is a position.”

My son came out of school and college (science degree) minus his faith. Puts him in a difficult position regarding his daughter, who after hearing about Jesus at primary school, wants to go to church, read Bible stories and know more about God, whom she clearly believes in completely. If she doesn’t get that at home, or at school, how is that a neutral education?

Jon,

You have raised a number of points. I am at a loss to understand how denigrating faith is a neutral position. Yet I also wonder if the current climate is providential; I have wondered at the ease with which ‘disciples of Judas’ (my phrase) have entered the hierarchy of the Church and have done incredible damage. Perhaps a period when the faith is ‘put through a grinder’ (given a difficult time) is needed. However it is a very difficult period for those who value the faith and life in Christ.

On the science and faith front, the situation borders on a mysterious period in history. The greatest arguments against materialism come from science, in that the certain aspects of science argue against the materialists’ worldview, yet they use science to bolter their position. How is that for irony?

In any event, I take a broader view, underpinned by “all things work for the good of those whose faith is in Christ”.

The greatest arguments against materialism come from science

I was thinking just that as I walked the dog just now, before reading your post. The idea of autonomous reason, for example, underpins the whole “objectivity of science” idea.

But empirically there is a wealth of data about how much the individual is influenced by his social setting (witness the way every New Atheist “skeptic” has swallowed an entire job-lot of the same arguments).

And theoretically, we know from developmental psychology that human beings are the product of societies, far more than societies are the sum of autonomous individuals.

As I’ve written extensively, autonomy was a Greek import into European culture, there being no real equivalent in the old Chrisytian theology of freedom.

So autonomy stands alone as an unchallenged worldview axiom, even to Christian scientists, even though both science and theology refute it. And it underpins the myth of science’s objectivity.

Jon,

Like so many profound matters, freedom is conflated with the odd term ‘autonomy’, and once that is done, the very ‘oddness’ of that concept maintains a debate that can be shown to be flawed. Freedom, be it choice for good and evil, or the very basis for the human personhood, is often used as a label, but deep reflection on what that means is lacking. I have formed the view that the singular meaning of freedom is found in the Faith, and this, once understood, is the strongest indicator for God and the Faith.

But yes, the Greeks settled for a half baked notion, and materialists have taken it as given – autonomy, to what? for what? I cannot agree with you that proper science is underpinned by this odd notion.

The clue is in the “proper”. Scientism, of course, is the belief that only science is truth, and certainly that is extraneous to good science – though common amongst its leading lights.

But more common is the idea that there is an objectivity to science that is absent from all other forms of knowledge – it is not just useful, not just a way to approach the truth of nature, but it is free of human bias and error. The underlying for that is that it relies on the “pure reason” of the truly autonomous individual, who is untainted by the superstitions and errors of irrational society. That is linked to the New Atheist term “Brights” of course, for the élite whose reason is least suspect (in their own eyes).

I’d say that is not “proper”, but is common enough to make the idea of leaving your faith commitments at the lab door sound not just incoherent, but laudable… one must not taint pure reason with lesser ideas like faith.

Science would benefit from being more humble about its role as just one more limited human attempt to discern truth – but that’s such a rare outlook that it’s hardly likely to happen soon.

Jon or GD — you earlier referred to Arthur Jones’ resources and above to: Arthur Jones’ chapter “Part III: Overview of the Sciences”

I must have missed where you posted links. Can I access this online? and where?

Merv,

http://www.allofliferedeemed.co.uk/jones.htm

The Book is on this site: Science in Faith: An Outline of a Christian Approach to the Sciences. Christian Schools’ Trust, 1998.

Thanks, GD.

I’m reading (and largely resonating with) Jones’ book. But short of having finished it, I already have a couple sticking points. (The Anabaptist is speaking here.)

So the secular paradigm is a badly deficient (no –even destructive towards Christian community) monoculture in our public educational systems. Agreed.

But what to replace it with? A theocracy? I guess you have that in Britain (at least symbolically) with the Anglican state church. But functionally … yeah, I see his point. But what does he want then? A serious theocracy? I’m all for any system that is not a secular monoculture, but he seems to want to eradicate secularism altogether. If schools were to get seriously behind promoting Christianity, I’m far from sure that such a thing could lead where Mr. Jones wants it to lead. In fact as a radical reformationist (long cultural memory) I have a pretty dim view of state-sponsored Christianity, which (as we can see now) gets pretty much all shot to heck ever since Constantine showed what could be done with it.

So maybe a plurality of religious schools? We could have private Islamic / Christian / Buddhist / (atheistic?) schools and let parents choose. That may be the plurality he wants, and it might help the self-identified secularists do a better job of bringing their own world-view out for critical appraisal. Maybe that is where Jones will go with all of it; I guess I need to finish reading. But it is no good decrying the unchallenged secularism without suggesting a replacement(s), so I hope he gets to that.

Merv

I originally pointed to Arthur’s stuff because it has some good ideas, not as a blanket endorsement, so I’m not rushing to his defence. But as I understand it he’s not writing to suggest a political programme, but to suggest a Christian educational programme within the existing secularist political system. “How to Run a Christian School” is the very last place to suggest overthrowing the established order (which would rather be called “radicalisation”!)

So yes, his aim I think is to produce adults who will act as Christian salt and light better because of their education. Since the “faith schools” system allows for other faiths to do a similar job, he’d assume (I think) that they will get on doing their thing for better or worst – that’s the price of pluralism.

So I don’t think political change is his métier. But there’s an implicit critique of the idea that secularism serves all faiths equally well – in fact it suppresses all faiths in favour of that of secular materialism. Still, I think he considers that for Christians to be a leavening minority is the norm for the gospel age, not the exception, so I doubt theocracies figure in his mindset.

Jones writes: “Christians have generally concluded that all God’s creatures are

optimally designed what they are (their structure) and what they do (their function) will be the best possible for their roles in God’s world. The principle would seem to be the only one consistent with the biblical teaching on creation, and with our experience of God’s world. It has been the expectation of Christians down through the ages. Even atheists have recognised how very well ‘designed’ things are. ”

“…only one consistent with the biblical teaching on creation”? That seems a bit narrow. And atheists have very much *not* recognized “how very well ‘designed’ things are.” They have been too busy pointing out all the apparent flaws.

I’m with Mr. Jones here that we need to presume the goodness of God’s creation as a whole, but our presumption is exactly that: a presupposition … just as much as the atheist’s judgment of flaws is also a presumption. I don’t think either is in a place to evaluate God’s creation as if we were on some kind of independent platform and could rate God’s work (and just exactly whose standards would be used in any such rating?) So, no, I don’t think we are in any position to assess “optimality” of God’s design (the Christian), much less the lack of it (the atheist). All we can do is praise God for his good work … good because he said it is, and because we are often privileged to glimpse it, if we choose, with some of the same pleasure as God allows us to see and understand.

Well, Arthur’s a Creationist…

No, that’s not a wholly adequate response. I only skimmed the book, but I suspect what you cite fits into his holistic approach to science overall – a cautious return to treating final causality within the subject. So in biology, not just treating classifications and structures and development, but ecological function (the assumption, as a Christian, being that the function is real, not just apparent – a straight worldview issue).

That would be of a piece with describing how limestone helps stabilize water systems as well as making quicklime when burned, aluminium’s role in living systems as well as in aircraft construction and so on.

One doesn’t, I guess, have to buy into the “best of all possible worlds” theme completely – but if not, then I guess one needs to integrate lack of optimality into ones holistic worldview/educational theme and not leave it hanging as an unexplained contradiction to creation doctrine.

“Well, Arthur’s a Creationist…” … as are most of us here. I’m totally with you, Jon, in your exchange with Gregory that we need not let popular culture have their way with an otherwise apt label. It just necessitates using constant qualifiers to avoid miscommunication.

Now I have read most of the rest of Arthur’s work, and see that he rejects evolution as part and parcel part of (or a symptom of) the problem he describes so well in his initial chapters. I still agree with his early chapters but his summary rejection of theistic evolution I might exacerbate the very problem he/we are trying to solve. The fundamentalist rejection of all things evolutionary is the very fuel that so strengthens the anti-religious fires of secularism. I probably can’t successfully recommend his book to any scientific friends over here because upon learning that he rejects evolution (I’m not sure if he rejected deep-time — don’t remember any discussion of that) they would automatically dismiss his whole effort … which totally confirms Arthur’s charge about the narrow blindness of secular thought.

The fly in the ointment (for Arthur, though) is … what if evolution actually happened? Plenty of Christian scientists are just trying to follow the truth and don’t have a secularist agenda to cover things up, and I don’t think Arthur is successful in turning over the massive evidence that is out there other than to blithely claim it can all be reinterpreted differently — and for the sole motivation (as the author himself admits) of conforming to *that particular* (–my added words those!) Genesis understanding. No amount of secular religious agenda can make an untruth true or vice versa. Let the whole world be a liar and the truth would still be out there.

All this said I totally agree with Mr. Jones about the dangerous stranglehold of secularism which, since I don’t reject all evolutionary thought, belies his claim that theistic evolutionists have succumbed the the secularist program. In fact, if I’m not mistaken, Jon; most of us here are counter-examples to that claim.

“Creationist” – it seems the term was first used for a supporter of the official Catholic doctrine of the creation of each human soul, as opposed to their being generated. So much for the fixity of terminology – though certain people seem to stake everything on it!

Arthur seems to me (with a PhD in biology) a kind of UK equivalent of Todd Wood. My last conversation was with him was 25 years ago, when I had far less developed views on this, so I’m not sure how much his negative view of TE is based on a literalist reading of Genesis (as British Evangelicals have a wide range of views on this) and how much on the metaphysical intrusions into the theory which, as we know, sometimes seem to impact on TE thinking too.

I still have to respect the intellectual integrity of many YECs (though I disagree with them). For example, fellow Cambridge grad Nigel M de S Cameron who, I discover, founded the Creationist organisation now headed by David Tyler (who commented on the education thread), also started Ethics and Medicine, which for most of my medical career was publishing the best Christian academic work in the field in Europe. As his biography shows, he’s already greatly involved in US biological science (like representing it at the UN!). Whatever any knee-jerk reaction of scientists may be, these guys ain’t no backwood hicks.

But horses for courses – I wouldn’t use a book on Christian education to evangelise a secular scientist either!

The acceptance or rejection of the A Jones’ overall outlook is a matter of what one chooses to believe (be it TE, ID, YEC, atheists, or whatever) – this does not directly address the validity or otherwise of the points made in the Part III of his book. The lecture by McGrath (Has Science eliminated God? Richard Dawkins and the Meaning of Life) is an example where the beliefs and metaphysical assumptions (what an outlook is predicated upon) are discussed without arguing anything on the science.

Jones’ has the intellectual honesty (in Part III that I referred to) to differentiate between those matters of science that we can take as sufficiently certain, and then ask, “What does all this say regarding Darwinian evolution?” The answer to this question poses serious doubts on Darwinian thinking – the measurements and observations of biologists and others is not in dispute – it is clear that “what is in dispute” is Darwin’s thinking on variation and natural selection. Yet few science teachers seem to be willing to say this out loud and most seem willing to look the other way, or to use nonsense such as “well, I think 70% is right, so I do not see why we should doubt. If a theory is 30% wrong (I do not know what such nonsense means), it is totally wrong. Scientific theory is not understood as part right and part wrong.

I am surprised that various religious people do not consider such a fundamental scientific question when they decide to incorporate Darwinian thinking into their theology. This smacks of an unwillingness to engage with science with sufficient intellectual rigour.

Questioning Darwin’s outlook by referring to ‘what is certain in science’ does not place anyone in any camp – perhaps religious people may get a healthy dose of doubt (or declare themselves agnostic regarding the pronouncements of Darwin) – the unhealthy aspect is for people to ignore what we know, and what we clearly do not know, and substitute an endless argument, be it between TE, ID, YEC, or any other group that seeks to react for or against Darwin. No matter how many ‘isms’ or versions of creationism are discussed, the matter always settles into two irreconcilable outlooks – the theistic (belief in God as Creator) and materialists/atheists. The latter will inevitably see the world as purely materialistic – some may become antagonistic towards those who do not, but so what.

Those who believe in God the Creator seem to show a propensity to create ‘camps’ of ‘groups’ when they indulge in incorporation of science in their outlook. This I think is a mistake.

GD, your point is well taken, that one not need have scientific agreement before appreciating (and agreeing with) Arthur’s main world-view points. And our making of camps — usually for the purpose of dismissing those in the “wrong” camps — is an impediment when it causes us to try to shield a theory from legitimate scientific probing. And most parties in their lucid moments agree there is much yet to question and learn about proposed Darwinian mechanisms such as are presented in our courses.

Jon, Todd Wood had come to my mind as well as I was reading Jones’ work, and I too was thinking of that comparison in positive terms even though I don’t share some of his conclusions.

In imagining a more pluralist approach in which secularism is, at most, just one paradigm among many others being nourished and allowed space, I was also thinking of the rich past in which science, (and intellect generally!) flourished. I know it may have been a predominately Christian outlook that prevailed and so nourished so many fledgling sciences, but it was far from monolithic. Imagine our impoverishment if we had rejected our mathematical bequeathment from Islamic scholars just because we didn’t share all their religious views. And some might say that sciences in the far east actually did fail to thrive perhaps because of their non-theistic philosophies. Yet still, imagine how much more quickly things might have progressed if the Europeans had not had to rediscover so many innovations that the Chinese had much earlier.

Also in need of noting … even if Europe did have something close to a monoculture in the theistic sense, it was hardly a unified one. One of the main driving forces of innovation according to Jared Diamond (and this may do more than any to explain why science exploded in Europe and not in China) was the ferocious competition between warring European nation states. The monolithic (and just a bit isolationist) Chinese empire of old had little to fear from its neighbors, while paranoid European leaders jumped all over any novelties coming their way lest their neighbor beat them to it. It isn’t a very peaceful outlook, but there it is.

On reflection, very few scientific propositions have undergone as much prodding, testing, and public explication to lay audiences as dating techniques, cosmological distance measurements, and evolutionary common descent. How much of all that would have happened were it not for the feared YEC? And yet for their being wrong about some things (as I think they are), it does not preclude their having some valid and desperately needed insights; Mr. Jones being just such an example.

Hi Merv,

I appreciate your points and agree to a large extent with what you say on how science has developed – but in one sense you are making my point because your focus is still on science. My point (which I seem to make with some difficulty) is to focus on the theology in these discussions, by pointing out that the Christian tenets of Faith have undergone enormous examination and reflection before they became Christian dogma, and this theological standard needs to be maintained. Science has progressed in a “messy” way as it must, with hypothesis, theories, speculation, error, corrections, and so on. The bio-sciences are no exception to this. Thus I maintain a distinction between Church dogma, and any other area we may discuss (be it science, humanities, philosophy, anthropology, sociology, etc etc).

It is this distinction that imo is lacking in many of the current discussions and controversies. If we wish to consider science within the domain of dogma (as faith requires), we must ensure that we have used the correct standard of certainty to the interesting areas of science that we think need to be included in our theology, otherwise we may make mistakes regarding Christian teachings – this does not mean that scientists should not speculate and even admit they have been wrong; it simply means that this is how science is done.

Scrutinising common descent, (to use one example, or any other major area of Darwinian evolution) is fine – but it is necessary to state that even here, we have the conventional ‘tree of life’, the ‘bush of life’ and from some people the ‘forest of life’. None of these aspects would make much of a difference to Christian teaching, since as far back as I can remember, we all have known that there were other people during the time of Adam and Eve (inferred from marriage and children to them) and I cannot remember anyone thinking this was odd. Thus is one example – now we do not need to make this Adam and Eve narrative, a part of a science class, but if we expand our view of science and teach children that Darwin contradicts the Bible, or anything that takes science outside its domain, we must be sure we understand what we are doing. Materialists do not have such a difficulty, since they disregard the Bible and thus everything is material/atheistic, and if scientific understanding changes, they would say so what. It is of small consequence to them. If we change of modify the teachings of the faith, however, because we put so much weight to science, then we may make serious mistakes. One of the mistakes has been the various ‘camps’ that spring up as some scurry in an effort to appear scientific and also of the faith.

I trust this clarifies the point(s) I have been making.

Thanks for the further clarifications, GD. I think I appreciate (and agree with) what I take to be your main point here that a revealed (and historically hammered out) theology should not be made subject to the messy changing winds of current science. The trick, no doubt, is to discern which is which on both sides.

I.e. we can probably consider it settled (not messy) science now to think of the earth as moving. And while you rightly point out that such things make no difference to our theologies, nonetheless any theology that would hold as one of its dogmas, say, that the earth is unmoving and immoveable, I think we would agree that such a theology would do well to let that dogma go and not conflate it with more important doctrines.

Hi Merv,

I am afraid that I do not understand your point – the example of the unmovable earth, to the best of my knowledge, has never been a dogma of the Church. That view has been a general one in the ancient world (articulated mainly by pagan thinking), and my reading of (for example) the Patristic writings shows that Christians simply acknowledged there were numerous views on such matters. The dogma was that God was the Creator – they would then expound on this as dogma. I have made a number of references, and provided quotes, that illustrate this difference. In fact in one of these, I provided as a quote, a summary of the prevailing (mostly pagan) views on such things as the shape and position of the world, and the speculations that prevailed during that period, and the theologians response to such matters. At no point were any of these presented as dogma of the Church.

Thus a further distinction must be made between popular views of any period on such matters, and the clearly articulated dogma of the Church. It is part of the atheists and materialists agenda to insist that prevailing views on things such as the shape of the earth, the position, and similar matters, were somehow part of Church Dogmatics and doctrines. This is false, but unfortunately people seem eager to accept such nonsense.

Perhaps I may challenge you (and Jon if he is interested) to locate a document that is a clear statement of Church dogma on the earth unmoved or similar matters. Indeed, this may be expanded to include any Church dogma that has been in need of ‘letting go’.

Hi everyone,

Jon pointed me to this topic as so many posts have referred to my work. So some background and explanation might help.

I went through school in the 1950s and ’60s when science was all the rage in the context of space exploration. That gave me an original interest in the physical sciences. But, like so many of my generation, I was the first in my family, church and community to go to university, so when I met the topic of evolution in A-level biology there was no-one I could talk to and there was almost no relevant Christian literature then. What literature there was tended to be poor as regards science or poor as regards theology and exegesis (or both!) In despair I decided to apply to university to read biology, so I could study it all for myself. Of course, that could have been disastrous, but straightaway I met, or was put in touch with Christian scholars who introduced me to worldview thinking and to serious Christian philosophy – to tools of analysis and critique that, often refined of course, I have used ever since. The biology lecturer who was my first year tutor and then my PhD supervisor was a liberal (atheistic!) Jew who introduced me to the history and philosophy of science (Popper and Kuhn in those days) – another area I pursued in depth in the following decades (see the annotated bibliography that is the appendix to my ‘Science in Faith’ (SiF) book). I also taught myself Hebrew and Greek and made full use of the superb theological library at Birmingham University. I wanted to be able to judge all the conflicting interpretations of the Biblical creation texts for myself.

By the end of my undergraduate studies I had become convinced that a creationist approach was best able to accommodate both the science and the theology/exegesis and this had become known in the Biology Departments. My PhD research was in evolutionary biology, allowing me to test different models of origins, essentially an evolutionary (universal continuity) model and a [‘creationist’ – I didn’t use the term of course] discontinuity model – natural kinds with many kinds of relationship, but not related by biological heredity/descent. I found (it was a genuine search) that the discontinuity model made most sense of the evidence I uncovered and I argued accordingly in my thesis (against the well-meaning advice of my supervisor). I never expected such a ‘heretical’ thesis to be accepted, but reasoned that what I had learnt and concluded could not be taken from me by anyone. Amazingly the external examiner, although a famous evolutionary biologist, turned out to be from an evangelical Christian background in South Africa. He had rejected Christianity as a young man (for ‘intellectual reasons’) but had no emotional or other hang-ups about Christianity. As a scientist he regarded heresy as something to be encouraged for the health of science – he, himself had come to reject Darwinism in favour of punctuated equilibrium. He was not all disturbed by my thesis and was prepared to admit (as I had argued) that this was primarily a conflict of faith (worldview) commitments. Amazing! To my surprise I was awarded the PhD.

As regards my ‘Science in Faith’ book(SiF) it may surprise you to know that we (my team of Christian science teachers) spent 6 years (meeting once every term) discussing science teaching, but hardly discussed evolution/creation at all and did not intend to have anything about it in the book! We wanted to counter the stereotype that a Christian approach to science was only about origins. We wanted a much more holistic approach. It was our sponsoring organization that insisted that we must discuss origins in the book.

My own convictions about origins were fed from several sources. The main source was my work on worldviews and in particular exploring the religious roots of evolution in the principle of continuity (the ‘great chain of being’ etc) – covered briefly in SiF in Ch 2.2. I read all Darwin’s writings including his notebooks and letters, from which it was quite clear that he early become a convinced materialist who was searching for a materialist theory of origins. That was the importance to him of his theory of natural selection, just as it has been to materialists right up to our modern ‘new atheists’. Take away that worldview commitment and the crucial evidence disappears – without the materialist spectacles, it simply can’t be seen.

My research was pursued from the perspective of developmental biology and one focus was on what was known as ‘cortical inheritance’ (or more generally as ‘cytoplasmic inheritance’). By the mid-1950s it was quite clear that the major part of heredity – the inheritance of the body plan (bauplan) or basic architecture of an organism – was not genic or genomic (not coded in the DNA) – but located in the cell as a whole (in the absence of any major research projects we still don’t know how it works). Since modern neo-Darwinism is a gene/genomic based theory, then it has been disproven for around sixty years! And since, as Dawkins writes, it is the only (materialist) show in town, there is currently no materialist theory on offer. There is much more I could say (and it needs qualifying and nuancing of course), but hopefully that goes some way to explaining my stance. There are brief discussions in SiF, Ch 1, Part III, section 4 and Ch 2, Part IV, section 6. See also Jonathan Wells (2013) The Membrane Code, online at http://www.worldscientific.com/doi/pdf/10.1142/9789814508728_0021

As regards my comments on the optimality of design, they were (and are) fuelled by research in biology. Whenever biologists look for design they find it and it is often found to be deeper and more extensive than they expected. Often (usually because of evolutionary assumptions) structures or functions are supposed to be undesigned (e.g functionless chance products of evolution), then if research is carried out, evidence of design is found. I have much unpublished work on this which I perhaps need to put online. There is a brief discussion in SiF at Ch 2, Part IV, sections 4-6.

In regard to politics Jon fairly captured my position in his response to Merv. I have never been arguing for the eradication of secularism or the imposition of Christianity (which versions?!), but for the recognition of the foundational role of worldviews. In other words, for a level playing field and for the possibility of genuine debate. It is a tall order in the modern secular world, but surely a goal we should aim for?

I hope these brief explanations may help those looking at my online materials.

Thanks, Arthur, for your responses earlier and here. It does help to know more of your background. The work and research you’ve done on these topics is impressive!

I don’t know if you are lingering to interact, but I’m curious whether you accept the various arrays of evidence for deep time or think that there too, physical scientists have fallen victim to their own inner spectacles?

In any case, despite my lingering difference over how some evidence can be / is interpreted even through a Christian lens, I have taken to heart what you wrote of world views and philosophies in your book available on line. Thanks for that!

And thank you, Jon, for bringing his work to our attention here.

Hi Merv,

I am very impressed (even thrilled!) with the topics and interaction on this blog, so certainly intend to be a regular visitor now.

My scientific expertise is in Biology (or more specifically in developmental biology and areas of biological history and worldview). I have no expertise in sciences relevant to ideas of deep time, so have avoided entering those debates. But I follow debates among the experts with great interest and do wonder about ‘deep time’, for two reasons:

(1) After decades of reading and studying the scholarly exegetical and hermeneutical literature, I still cannot reconcile the Biblical storyline from creation to new creation with the idea of deep time. The teasing question I always put to ‘evangelical’ (or whatever term you prefer) TEs and OECs is ‘Why don’t you have the same idea of ‘deep time’ in your eschatology that you have in your creation theology?’

(2) None of my PhD research in biology pointed to, or indicated a need for deep time. I was studying the Cichlid fishes ( a famous group of around 2000 species in the tropical freshwaters across the world from the Americas to Africa to Madagascar, to India and Sri Lanka), which are regularly cited as an example of ‘evolution in action’ and of ‘adaptive radiation’. Actually I found nothing in my research that indicated evolutionary novelties (rise of new features), just endless permutations of a (presumably) primordial, and relatively small set of possible specific expressions of each generic feature. These permutations were spread ‘randomly’ or in ‘mosaic’ fashion across the global distribution. Nothing indicated any need of deep time. Where time could be fairly accurately measured (e.g. new cichlid species in recently formed lakes such as in volcanic craters, or recently cut off arms of larger lakes) we were talking about hundreds or thousands of years at most. I also studied the fossil history of the Cichlids and that led me in to a wider study of the fossil record that uncovered a very puzzling fact. Evolution texts regularly tell us that 99% (or 99.9% or even 99.99%) of all species that have ever lived are now extinct. That is actually an evolutionary assumption (that we only have the outermost twigs of the tree of life today; the connecting branches and trunk represent extinct species). There is in fact no empirical evidence for it. Known living species outnumber known extinct species by at least ten to one. The majority of fossils are of creatures still alive in the world today. In that regard books about fossils give a quite misleading impression, but obviously readers who turn to these books want to learn about extinct creatures. Of course this also brings into question the assumption (to explain the general – and systematic – absence of missing links) that the fossil record is very incomplete. But the only empirical test we can make of that assumption is to look at the representation of living species/groups and almost all are well represented, even those (like birds, or creatures with no hard skeleton) that fossilize poorly. Well, as I say I keep out of the debates, but I do wonder …..

I stopped by to see what was going on here and found this. Against my better judgement, I feel compelled to comment that a biologist would have to be very careful about where he looks if he hasn’t seen evidence of deep time in biology. And of course he must never open a geology book, or a physics book, or an astronomy book.

It is not proper to treat this kind of worldview as equal to a theistic evolution worldview or a standard scientific worldview. Even though all worldviews involve presuppositions, some are better than others. One can have presuppositions about the world that are demonstrably wrong, or that require exorbitant ad hoc hypotheses in order to preserve them.

We can fool ourselves but we can’t fool nature. The evidence for common ancestry of all vertebrates (at least) is strong enough to establish this common ancestry as an empirical truth. Even in Darwin’s time there was enough evidence to convince many devout Christians who were not materialists. With the advent of genetics and the observed concordance between gene-based phylogenies, karyotype phylogenies, the fossil record, and the geological and astronomical record, the evidence for deep time is overwhelming, and this leads to innumerable verified predictions that contradict a young-earth view.

Merv, Arthur will answer for himself, but a reply from me might also serve to ask for responses to the OP, which I think made a significant point (though I says it as shouldn’t…).

I’d see a young-earth belief as a persuasion, rather than a world-view commitment, though arising from it. If ones worldview is based on “Christ as Lord”, God speaking truth follows, and by a deduction one might say God would therefore speak truth in his Bible, which appears to support a recent creation. If that were the reasoning, then it would lower the threshold for accepting alternative explanations for, say, dating methods, and make living with anomalies in that area a reasonable cost… just as a materialist might accept optimised functions as anomalous to trial-error evolution, but not enough to overturn the overall appearance of ateleology that arises from his worldview.

But if one comes to believe that God could speak truthfully in Genesis but still leave an old-earth explanation likely, then the same worldview will enable a significant change in actual beliefs.

On the face of it some phenomena argue more against creation than for it – the “best” example is often said to be the suffering in nature, which a good God “wouldn’t” create. Actually, that’s a two-edged sword, since thorogoing naturalist materialism has to say that consciousness is an illusion, and therefore conscious suffering must be too – so you need God to create the suffering before you can be morally scandalised by it and deny his existence!

But Arthur suggests that much of the case for evolutionary mechanisms, and even common descent, disappears from view without the materialist worldview, and there’s much to be said for that. In my post I suggested that “contingency” suggested primarily “divine choice” to the early Christian scientists, but to the materialist (and those who have imbibed their worldview) it necessarily suggests “chance”.

Now I’m with Dembski and Co who say that there are ways of distinguishing the two – relatively high probability and lack of order suggest chance (without precluding divine providence), whereas very low probability and complex organisation suggest choice. But worldview surely dictates the understanding of what you observe. To George Muller, a sixpence in the gutter was evidence of God’s special providence (not too unlikely, not that organised, but meets specific need), whereas to a materialist even the Resurrection or the origin of life is probably just a fluke, even if it requires a multiverse to load the odds.

Woops – Arthur posted whilst I was writing the above!

Arthur

I’m flattered by your praise of our humble enterprise…

The disproportionate paucity of fossil species has intrigued me too, though I’m inclined to attribute it to non-gradualistic changes in suites of fauna and flora rather than the gradual depletion of an initial plenitude. I consider that the old explanation of gradualist Darwinian evolution and radical ablation of the fossil record doesn’t wash, because of the seldom-mentioned abundance of actual fossils of each type – on which I wrote here.

As a matter of interest, is your PhD thesis available online anywhere?

In today’s world, in any given ecosystem there are usually a few abundant species and many more very rare species. In groups with high diversity, like plants and insects, the modal number of individuals per species equals unity (i.e. most species are represented by only a single individual). It can be shown mathematically that when high-diversity sites are severely undersampled, there is likely to be at least as many species missed by the sample as there are species represented in the sample by single individuals. (Merv, the math involved is wonderful and simple and surprising!)

This shows the main argument about fossils in your linked post is not correct. At least some of the anomalies you described have simple resolutions if species in the past had abundance distributions similar to those found today. Some species will be very abundant and will be more likely to be fossilized. Most species will be rare and will likely be missed in fossil digs, just as we miss many species when taking small samples of live creatures today.

I should add that we can put a good lower bound on the actual number of undetected species present in an area, based only on the characteristics of the sample, if the sample is not too small. A lower bound for the expected number of undetected species in the area will be (s^2)/(2dn) where s is the number of species known only from a single individual in the sample, d is the number of species known from exactly two individuals in the sample, and n is the size of the sample. This is the Chao estimator, named after my colleague Anne Chao. We use this often in our papers. We can also estimate the fraction of the population made up of the species not found in our sample: 1-(s/n). This is the “sample coverage”, discovered by Alan Turing, another key formula we use often. This is just math; no special materialist assumptions are involved, though we do have to assume that the individuals in the sample were randomly selected (generally true in ecological applications, but not necessarily true in paleontological applications).

PS – I see cichlids were in the news today – it seems they have very good memories, despite the usual Fishist prejudice against them. I forgot to mention it above…

Well! That affirmation of cichlids having very good memories would not be news to anyone who has kept them for long periods. I had several fascinating examples over the years I was doing my research, but, as it was not a focus of my research, I never mentioned it in papers or thesis. I expect that has been true for many other cichlid researchers. There must be an awful lot of important but unmentioned findings lost in the ether ….

There must be an awful lot of important but unmentioned findings lost in the ether ….

Here’s one…