Enter, stage left, the Great Chain of Being…

This, an idea common to much ancient Greek philosophy, held that all that exists is linked in a continuous chain, or hierarchy, from top to bottom. As we saw in the last post such ideas had little impact on early Christian thought, which though interacting with philosophy was fundamentally biblical, and concerned with religious truth, leaving science to the scientists. Exceptions were writers like the mainly Platonist Origen (whose views were considered flaky as a result) and, notably, the heretical Gnostics.

The Gnostics promoted Platonic and Middle Platonic ideas of a heavenly hierarchy from intrinsically evil matter to God, via an incompetent Demiurge who actually made us. In the third century the pagan Neoplatonist Plotinus

…taught the existence of an ineffable and transcendent One, the All, from which emanated the rest of the universe as a sequence of lesser beings. Later Neoplatonic philosophers, especially Iamblichus, added hundreds of intermediate beings such as gods, angels, demons, and other beings as mediators between the One and humanity.

All this was of little interest to most orthodox Christians. By the time of Maximus the Confessor (see previous post) the Western Roman Empire had more or less ceased to exist for a century after barbarian invasions and internal strife. It was culturally cut off from the eastern empire based at Constantinople, which in turn became increasingly beleaguered by barbarians and then by the Muslims. Greek literature was therefore largely lost to the west. The Christian most effective in limiting this loss was Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636), “the last scholar of the ancient world”, who tried to compile a rather uncritical summa of universal knowledge, the Etymologiae.

Our old Saxon friend St Bede used mainly Isidore and the Roman Pliny in his brief cosmology On the Nature of Things (c703). Like most educated Christians he accepted the Classical view that the earth was spherical, and he includes an Aristotelian hierarchy of the four elements:

“Nature contains [the earth] and denies it any place to fall” (Pliny, NH 2.65.162). Situated in the centre or pivot of the world, the earth, being heaviest, holds the lowest and central place in creation, since water, air and fire as it were by the levity of their nature and likewise by their situation rank above it.

Otherwise, there is no real sign of the Chain of Being in Bede – his book depends on ancient knowledge of natural history, but little on philosophy.

Things began to change greatly around the turn of the millennium, as Christian scholars became more interested in Greek works from the East, but there was a massive surge when translations from Arabic sources became available in the late 11th century, especially translations of the works of Aristotle, who had been almost forgotten since the 7th century. Thomas Aquinas, of course, was responsible for a thorough synthesis of Aristotle, plus a bit of Plato, with Christianity – but at a cost.

Ptolemy, the astronomer and astrologer, was also translated into Latin in the 12th century, giving his cosmography greater prominence. Ptolemy was an Aristotelian, and his geocentric scheme, corresponding to Aristotle’s scale of elements, was intrinsically heirarchical and theological. Suitably christianized, his outer Empyreum, seat of the prime mover, became God’s heaven. The earth became the universe’s lowest and least prestigious place (though hell was soon placed at the earth’s centre), and so separated from God by a hierarchy of celestial spheres.

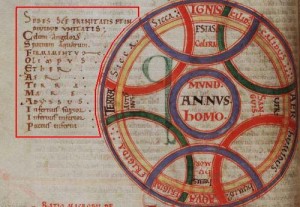

Society and the Church having become more heirarchical too, this cosmological “gradualism” became increasingly appealing. Already, as in the 1110 manuscript to the right, a hybrid spiritual hierarchy had been attempted. Translated, the box reads: the throne of the triune God -> angelic heaven -> upper waters -> firmament -> Mt Olympus(!) -> aether (the finest, 5th element) -> air -> earth -> sea -> the abyss -> three layers of hell. Compare that to the Hebrew cosmic temple or the God-suffused cosmos of St Basil – it’s very different conceptually.

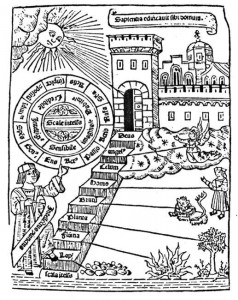

Aristotle’s natural history formed a hierarchy too, in this case (on the left) ranging from minerals up to God, who was once more separated from his creation (including man) by intermediaries. Through the classical infatuation of the Renaissance, this top-down layering became as much a universal principle of existence as evolution is today, whether the world was considered physically, biologically, intellectually, politically, socially or spiritually.

For example, in Elizabethan times, your social status dictated your dress, in whose presence you removed or donned your hat, and so on. The Aristocracy was of a higher divine and natural order than the peasant. What had been due respect for God-ordained worldly authority in the Bible became the Divine Right of Kings in the sixteenth century. So by the time of Francis Bacon’s great influence, the physician Robert Fludd (1574-1637), as we see from this alchemical diagram nine ranks of spiritual entities, nine astronomical/astrological levels and three elements separate us from God – the chain of being has grown exceeding long. In common with most natural philosophers then, Fludd believed in the cosmic harmony of magic – under God, of course – as I described in a previous post. So here the planets are truly in a spiritual continuum with the “powers and principalities”, as well as in a physical relation. The brackets in the diagram represent various supposed Pythagorean harmonies, the basis by which not only astrology but natural magic and medicine were held to work.

It would seem from all this that by integrating the once lost classical philosophical ideas into Christian cosmology Western civilisation had managed to produce an integrated system of knowledge that unified pretty well everything from fundamental physics to theology.

What that meant for science was a mixed blessing: clearly early modern science kicked off partly from an Aristotelian, Pythagorean and Platonic intellectual foundation, but found it quite hard to jettison its errors along the way. Bacon’s idea of controlling nature for man’s benefit came partly from the Hermetic magic recovered and developed by the Renaissance humanists, just as its mythical drive came from the example of Prometheus. But these were balanced and eventually displaced by the greater influence on those like Boyle and Newton of Christian creation doctrine.

The effect on Christian doctrine itself was arguably even less productive. Certainly classical philosophy gave theology a language of ideas that is still valuable today – the Patristic authors had discovered that right at the start of Christian thought. Aristotelian metaphysics, in particular, still has much to offer theology. But the synthesis also tended to take theology into strange places, not only encouraging a very different religious world from that taught in the Bible, but also giving Christians a view of the natural and human worlds which was very different from the Scriptural worldview, and in fact much less life-enhancing.

One could see it as a five-century-plus object-lesson in the dangers of submitting your theology to outside authorities, whether they be from science, philosophy or metaphysics. Needless to say it all seemed perfectly obvious intellectual progress at the time, compared to the unphilosophical theology of the old guys like Basil.

What happened next was that the Great Chain of Being began to break up, so that there was no longer a united religious and scientific view of the world. Whether that’s a good thing or a bad depends partly on how much you feel the classically-influenced mediaeval view represented either physical or spiritual reality truthfully. I’ll let you make up your own minds on that … after the final part of the series.

Jon

All of this is interesting, but I wonder if you have ever asked yourself whether the kind of analytical history you are engaged in with this series has biblical warrant as a means to spiritual truth. Do we take for granted that intellectual exercises such as this have spiritual value because of extra-biblical cultural influences?

Darek – That seems a slightly extraordinary question to me, since the Bible itself is chock-full of analytical history, comparing the tenor of its times with the biblical norm of Torah (and indeed the Torah itself is just such a history), and using it to call for self-examination. That, of course, was written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, but I would hardly expect the Bible to say, “Thou shalt/shalt not study history.” There are plenty of admonitions to consider the former times and learn from their example positively or negatively.

The Reformation happened because of an analysis of the “Babylonish captivity” of the Church and the desire to reform what history had perverted. It relates directly to this post because seeing the Pope as usurper to God came from challenging the Chain of Being (I missed out the particular version with the priestly hierarchy because my general subject is “creation”, not “ecclesiology”).

On the positive side, there is the old secular adage that “those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it.” It’s a feature of the anti-intellectualism of fundamentalism (even in this country) to say “We don’t want to hear what people thought about the Bible then, for we can read the Bible directly.” Such people are blind to that fact that they don’t have the real Bible, but only the Bible their prejudiced worldview lets them see. Until the worldview is examined historically it remains invisible. Funnily enough one of the deacons of my church said to me on Sunday, “People don’t know enough church history nowadays.”

Thirdly, all truth impacts on spiritual truth, but I don’t recall saying this series was setting out specifically to find the latter. I noted, with interest, the trends in western thought, and the impact they had on doctrine. That seems a major role of church history and why it’s always been part of the Church’s life (witness Eusebius for the early Church, Bede for the English, Neal for the Puritans etc.)

If James Penman were about the site at present, he would, as a Church Historian as well as a pastor have something to say on the issue.

As a word of caution: doing history is never an objective listing of facts, but is a story being driven by commitments. So I get irritated when you list Eusebius as Church historian. He does write a history of the Church, but in a similar vein to someone like Paul Tillich.

They’ve lost Christ as hermeneutic for something else, whether it be the Imperial Throne or Hegelian-molded modern philosophy!

I agree no history is objective, cal, and that Eusebius had an agenda of support for Constantine (not surprisingly at the time, after the persecutions had eased). But the Introduction of the Penguin edition, by Andrew Louth, takes a much more sympathetic view of the History overall, suggesting that Books 2-7 were published before a Christian emperor came on the scene.

And whatever his own motivation, the Church has long used it as almost the only source for understanding that period of Christian development. It remains valuable long after Constantine (and Arianism) have lost their lustre.

Jon

I leave it to your readers as to whether the kind of putatively objective, historical survey-of-ideas-with-analytical-commentary you are engaged in bears comparison with any biblical genre, much less the Torah. Anyone can read your material (or any similar academic-style research and analysis) then begin in Genesis and decide for themselves.

I do not claim that academic, intellectual treatments or modern historical analyses lack value. I’m saying that what value they possess is rationally self-evident. Like the methods of science. And if they stand or fall by their rational merits, then their intellectual pedigree is not the decisive factor in evaluating them.

I still don’t see theproblem, Darek. The aim of writing this was to get people to start in Genesis and decide for themselves, but in the light of, perhaps, understanding where some of the interpretations that are out there came from.

I’m not sure if you’re suggesting that we can come to Scripture blissfully free of the prejudices of our background: your experience amongst Fundamentalists surely gives that the lie.

Darek:

I’ll let Jon provide his own justification for the method in his latest series, but I will add a comment to your question, relevant to our previous exchanges. You are concerned about establishing a “biblical warrant” for spiritual truth, and you seem to be cautioning against the possibly distorting effect of “extra-biblical cultural influences” upon our perception of Christian truth. Well, that is exactly my concern; hence, I tried to make the point that liberal Christian theology in general, and much TE theology in particular, is very much shaped by the “extra-biblical cultural influences” known as “the Enlightenment” and “modern science.” The very strong theological preference for a God who is not constantly personally interacting with nature, but establishes and sustains natural laws and then lets them run, comes from these “extra-biblical cultural influences.” To Calvin, Luther, Melanchthon, Bucer, Zwingli, etc. — the spiritual and theological fathers of Protestantism and hence the spiritual and theological grandfathers of American evangelical faith — this preference for a God who is not directly involved in a personal way (i.e., beyond merely establishing natural laws) in the creation of the world would be utterly incomprehensible, and no American evangelical today would have that preference if Western civilization had not since gone through the rise of modern science and the Enlightenment. There is much less “extra-biblical cultural influence” in the writings of Calvin and Luther than in the writings of Francis Collins, Ken Miller, Darrel Falk, Karl Giberson, Dennis Venema, Denis Alexander, etc. I think this is not an unimportant point to make whenever someone raised the question of “biblical warrant” for Christian beliefs.

That said, I look forward to Jon’s answer to your question.