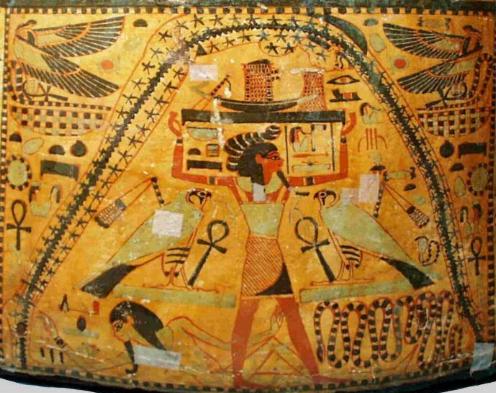

This recent highly-commented post, and a local request to teach on the recent insights into the biblical creation story, have put my mind back on to Genesis. I’ve use this illustration before:

My aim in that piece was to show that to the Egyptians, the real cosmos was divine, and the mundane physical world something that was perhaps illusory, or epiphenominal, in relation to the gods. In other words, they weren’t that interested in what we would call the “literal” understanding of the world. You don’t actually find landscape, or skies, represented very much in Egyptian art as items of interest in themselves. And even if you do, they’re often coded spiritual messages. If ya wanna understand an Egyptian, ya gotta walk like an Egyptian.

Enough of that. Nevertheless, in this picture, one can say that there is some “literal” truth, only it would perhaps be better to describe it as phenomenological truth; that is, it describes some of what the senses experience of nature rather than what the mind and heart (or was it bowels in those days?) infers below the surface of things. What constitutes this phenomenology is pretty basic – the sky and the stars are over the top of the earth, which is underneath and fertile. The sun moves through the sky from east to west, below the stars, and so on.

One could tell a similar tale of what we are now understanding about the Hebrew creation story, and in particular (for the purpose of this discussion) its role as a functional account of creation as God’s temple. This understanding is the meaning in the same way that the Egyptian gods and goddesses were the meaning of the illustration. The story is not primarily about phenomenology, but about the spiritual truth underpinning it. One can say that to the Hebrew mind, the physical structures of the universe are epiphenomena of its reality as God’s cosmic dwelling, and of the earth’s reality as man’s domain of control. “Symbolism” is actually an anachronistic word to use of this (Owen Barfield’s “participation” being a better if less familiar descriptor) but if we did use it, we ought to realise that the temple imagery is not symbolic of physical reality, but the physical appearance symbolic of the spiritual reality.

Now, since Genesis 1 is nevertheless a description of the actual world, rather than some fictional realm, phenomenology is clearly as present as in the Egyptian account. The meaning of the world is only perceived through the impressions it makes on the senses. It’s almost superfluous to describe them here, for Genesis 1.1-2.4 is so well known. But clearly the divisions between the heavens, the atmosphere, the land and the sea are clearly identifiable to us. So also are the plants, the heavenly bodies, the animals and man himself. All these are actually described functionally, and with rich allusion, in many cases, to temple imagery. But they are still the stuff of daily sensory experience then and now. For the most part, they are uncontroversial.

Ah, but what about the firmament? That’s the raqia, the solid dome of all those modern “ancient cosmology” diagrams. Well, the raqia may indeed be an inference from the phenomena – an ancient idea that you needed a solid roof to keep the waters out. But as I pointed out here it may just as plausibly be part of the inferential, non-phenomenological, temple imagery – a temple needs a solid roof, or the tabernacle a fabric canopy (an alternative derivation for raqia), just as a temple needs pillars such as those in Job’s poetic imagery about the world. As I pointed out in the link, raqia always occurs in Scripture in relation to God’s glory. And though the word is not used of the theophany of Exodus 24, in that account the pavement underneath God’s feet is blue like lapis lazuli, clear as the heavens (shamayim) – and interestingly there the elders of Israel see a vision of God and eat in his presence without apparently having to find a trapdoor to break through.

OK, so the firmament may not be primarily phenomenological – but what about the waters? Is not a false scientific perception at work here, believing space to be full of water rather than … well, what word would you have substituted in a “literal” account, if indeed the waters too are not intended to have a representative meaning rather than being a phenomelogical description “at surface level”? “Surface” is a significant word here, for the usual modern materialistic interpretations of Hebrew cosmography don’t actually leave a surface over which the Spirit of God might hover.

The waters in Genesis 1.2, together with darkness, actually function as a proxy and parallel for the tohu wabohu, “functionless and empty” referring to the earth. And note that much of the initial creation consists of pushing the “chaotic” waters aside to make sacred space, whilst actually taming them as part of his cosmos. Throughout Scripture, “the waters” retains the idea of elemental chaos: remember the Flood, the parting of the Red Sea, the flight of Jonah, Jesus’ calming of the storm, Paul’s shipwreck and the absence of ocean in Revelation’s New Jerusalem, to name just a few instances.

For these reasons it seems to me that the waters, like the firmament, may be part of the language of cosmic temple-building rather than of the superficial phenomenological framework of the account. But supposing that’s not the case, and it’s intended as a physical description, what word would be better for the basic stuff of the cosmos than “waters”? A century ago it would have been “the aether”, a medium of totally speculative nature derived from the belief that nature abhors a vacuum and that, in the heavens, there would need to be a special, fifth, celestial element. Linguistically “aether” is derived from “burning”, so a Victorian scientific account would simply substitute imaginary fire for metaphorical water.

Would “vacuum” be better then? That means “emptiness” – but we don’t actually believe space is empty, either of matter at large and small scales, visible or dark; or of energy, also detectable or dark. So “vacuum” would be unscientific too – even if the concept of a vacuum could reasonably be expected to figure in ancient Hebrew, at a time when no vaccuums likely existed on earth.

Nowadays, what we believe to be beyond the atmosphere is the space-time continuum. But that’s just as ubiquitous under the firmament as above it, even now. And what is it anyway? A continuum is something continuing – and we believe it’s “space-time”. Which is what, exactly, in simple English, let alone simple Hebrew, let alone as a concrete mental construct? It’s a metaphor for a mathematical equation, isn’t it?

OK, leave all that aside. We can still wish that the Hebrews had written a more obviously scientific account, one that reflects what we now know to be the case rather than an anthropocentric phenomenological account with spiritual undertones. It would include a Copernican system, for example – with some differentiation between the self-lit sun as opposed to the merely reflective moon. We’d prefer a gaseous atmosphere, held down by gravity and surrounded by … that aether, or vacuum, or space-time continuum or whatever we decided it would be this year. A definitely spherical earth would help, together with, perhaps, some more rigorously morphological or genetic biological taxonomy. And of course, the time dimension would deal with thirteen billion years rather than the seven days of an ANE temple-inauguration text. That would at least be scientific, and save God from the suspicion that he trained in the humanities instead of the sciences, and prefers involved mythic metaphors to good solid knowledge.

But as far as I can see, such an account wouldn’t actually be scientific at all – it would just be an updated, rather more sophisticated, phenomenological story. For isn’t it the claim of materialistic science that nothing about the world of sensory perception is what it seems? Our senses, even our minds, were developed for survival, not truth – our perceptions are illusions, we are told, constructed symbolically in our brains . As Arthur Eddington exhaustively outlined back in 1926, in the wake of relativity and quantum theory the mundane “appearances” of the world are very different from the scientific reality of quantum events, and of relativistic time and space. The kind of account often suggested in lieu of Genesis 1 is actually a Newtonian model, in which solids are solid, time is linear rather than feeding reciprocally off space, and you can describe the formation of the cosmos as if there were a fixed point from which to do so. In other words, it’s really another form of superficial phenomenology.

. As Arthur Eddington exhaustively outlined back in 1926, in the wake of relativity and quantum theory the mundane “appearances” of the world are very different from the scientific reality of quantum events, and of relativistic time and space. The kind of account often suggested in lieu of Genesis 1 is actually a Newtonian model, in which solids are solid, time is linear rather than feeding reciprocally off space, and you can describe the formation of the cosmos as if there were a fixed point from which to do so. In other words, it’s really another form of superficial phenomenology.

A truly scientific account in Genesis would require that one looks below the deceptive surface of sensory phenomena to the hidden truths beneath. Granted, in our current state of knowledge that would require maths completely unavailable and incomprehensible in ancient Israel (and for most people in the modern West), as well as the use of themselves highly metaphorical, homely terms like “firmament” and “waters” “particles”, “waves” and “fields”. Maybe it would even require a picturesque Bang, and something “inflating” (literally having air blown into it!). In other words, we’d have replaced a purely phenomenological account with a more accurate one dealing with hidden meanings beyond the usual senses’ abilityto discern …

… a bit like the account we actually have in Genesis 1, in fact.

The intense interest in Gen 1 and 2, and the endless debates on how this (fits/does not fit) with our scientific understanding, and especially evolution, has I suppose, caused me to ask myself, just what is it that I am considering when I read these chapters and think ‘literal’? A simple question, but on reflection I could only come up with one answer.

I think that the writer(s) of Genesis first and foremost were undertaking an act of worship of the One True God. They would also (as is so often stated in the OT) be very conscious of the great powers surrounding them and the impact these would have on the Faith of Israel, and intrinsically to their national identity. This is as close as I can get to a “literal meaning” in Genesis. Literal may nowadays mean lacking imagination, or expressing something in a matter of fact way, and able to exactly define each word and relate the resulting sentences with something factual. But literal is also, at its most basic, the language and its meaning for the person/people who speak it, and find such communication meaningful (more than culture, as culture grows from this language activity).

When reflecting on the latter, my view is that Genesis is particularly literal, as it deals with the very beginnings of Israel and their worship of God – this means the heart, soul, and meaning of their identity and sense of being. We can get a sense of the depth/identity of Jews from Romans, especially Rom 9 – I feel that we may not fully appreciate how ‘literal’ the teachings of Moses may have been for devout Jews.

Some of the areas mentioned in Genesis would appear to us to be unscientific, and I would almost sympathise with people these days who equate a ‘literal account’ with a scientifically examined and articulated one. Yet I agree with Jon in that we need to understand the entire literature, language and sense of identity of ancient people and their writings, before we become critical of any scientific shortcomings we find – this modern attitude says, “If I were to write Genesis, I would do a much better job”. As to why God would not reveal science to the Hebrews, I cannot stop laughing to come up with a serious answer (?).

As I write this I recall, many years ago, finding accounts of Homer in which questions were raised if Troy was imagined or real (and if Homer was historic). It seems as if it was: (a) imagined for some time, (b) they had a dig in that area and found remains, so it was real, and (c) they overthrew (b) but then someone found better remains, a bigger city, and they declared it real – although I suspect many scholars will bring up this theory, or that evidence … and on it goes.

Yes we may argue for a phenomenological outlook, but I suggest it is deeper than that – it is literally the entire range of language and meaning at the deepest level of a human being – when we consider it in this way, Genesis begins to make sense, and when we forget how clever we are, it also becomes instructive to both Jew and Christian.