Here is a link to chapter 6 of my book.

In it I examine the possible reasons for the apparent shift from a generally optimistic picture of natural Creation in the older writers to the pervasive modern pessimistic one.

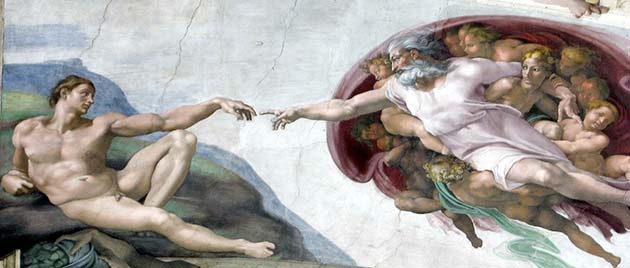

You’ll see that I lay great stress on the myth of Prometheus, which I think is a highly significant factor whether taken literally (the influence of the myth itself on early-modern thought) or more figuratively as representing attitudes to God and man that became general at that period. Some may be interested in the mental process that led to this conclusion.

As Nick Needham and I shared more and more ancient sources back in 2012, a clear demarcation began to emerge between sources before the time of Reformation, and those afterwards. It was hard to see any theological reason why such a change should have occurred – and especially since it seemed to be far more prominent amongst the Reformers than their contemporary opponents. So I began to search for possible explanations by reading about the changes in the intellectual landscape around that time.

I was particularly struck by the anthropocentrism of the Italian Renaissance, to which Cameron Wybrow draws attention in his book, The Bible, Baconianism, and Mastery over Nature, and which is well expressed in the rediscovery and development of the Prometheus myth. This is dealt with in more depth in Ernst Cassirer’s classic The Individual and the Cosmos in Renaissance Philosophy. The Prometheus myth excited me as seeming to explain a lot about the attitudes of our own culture to many things from science to free will.

Around that time I finally took the trouble to look more closely at a Greek quotation that John Calvin uses in his commentary on Genesis 3.18 (the “curse on the ground”), which I’d ignored as merely being a classical bolster for his rather innovative view of the fallenness of nature. I realised with a shock that it refers to the Prometheus myth (or strictly, to the related story of Pandora), and that here was a direct application of that myth to a key text for the concept of fallen Creation which I was tackling.

For a few days I had (for the only time in my life) that feeling scientists occasionally get of knowing something that nobody else has discovered before. I still feel that to be true, though the shrugging of shoulders from various people who have read my thesis suggests that to them it is about as persuasive as cold fusion.

But you can judge for yourself, and come up with a better explanation if you have one. And meanwhile, even apart from its application to “Fallen Creation” doctrine, I suggest one can understand a lot about our current culture, and how it cuts across the biblical worldview, by bearing Prometheus in mind.

![Prometheus creating man in the presence of Athena by Jean-Simon Berthélemy (1745-1811), Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse (1784-1844) (Jastrow (2008)) [CC BY 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://potiphar.jongarvey.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Creation_of_man_Prometheus_Berthelemy_Louvre_INV20043.jpg)

Interesting idea Jon. I’ll have to investigate it a bit – I have a few learned friends who might have some knowledge in this area. For a topic that the Scriptures say little about it certainly has a big impact on what we believe.

Indeed – it affects how we relate to the world (including how we treat it), how we view God, how we view man’s role, how we regard eschatology and the Christian hope. And probably a lot more, too.

I’m so glad you alluded to chapter 11 here. It means (I hope) that we have much more of your treasure yet to come as you are willing to share it with us. I devoured these last couple of chapters with intense interest. you’ve sold me…hook line and sinker. But your job in my case was pretty easy since I grew up with a father who was constantly waxing in eloquent echoes of the psalmists about the amazing and beautiful intricacies of nature. Never a peep about how nature was allegedly now evil, fallen, or corrupted. Now my dad was not deeply read among too many of these theologians (not to my knowledge anyway). But he must have had a scripture-based intuition in this question (and his old bible on my desk in front of me is quite marked up and tattered) that saw him through and, I would like to think, planted those seeds in me too. So in a dangerous flourish of total confirmation-bias I want to shout “yes! –I always knew this” and then thank you for filling out this intuition with some real scholarship.

Maybe you’ve got more coming on this (your allusion to future chapters), but I wonder then if there is any Christian blessing or baptism on any kind of Promethean theme. Stories like the tower of Babel would seem to indicate almost exactly the opposite, and perhaps deny any place at all for our enlightenment ambitions. I wonder if any of the reformers apart from Calvin, Luther, or Wesley were able to stay some what immunized to the Promethean myth while yet seeing something of God’s blessing in any of modern man’s current projects.

Hi Merv

Thanks so much for your positive response! I have to say that the principally theological side of the book is more or less finished – most of the rest is about the physical world itself, and the pessimism of so many, and especially those within science, towards it.

I should stress, I think, that according to my thesis the early Reformers were actually reacting against the Promethean worldview by their emphasis on sin, grace and God’s glory. But because they were operating within that very worldview, they failed to dethrone man from his Promethean centrality (ie man couldn’t fall without taking out the whole cosmos too).

It’s a bit like the way we may resist buying the brands the advertisers bash us with, but still unconsciously buy into the consumerist lifestyle that is the medium of advertising. Or another example is the (moderately) well-described one of Creationism arising as a reaction to Enlightenment materialism, and yet adopting a largely materialistic approach to the biblical narrative.

That being the case, we ought to look for nuance rather than reactionism. To see through the Promethean myth is not to dismiss human exceptionalism, nor to make Babel a paradigm for hating all innovation*. Indeed, it is the exceptional nature of mankind that powers the Eden narrative – and we’re conveniently placed, knowing that the Renaissance tended literally to transform Adam the sinner into Prometheus the saviour, to compare and contrast the two approaches.

So it’s possible to see exactly how the myth perverted the biblical story, and use that insight as a microscope on any particular phenomenon, be it theological, sociological or scientific.

*That reminds me of a gig I played at a Manchester Methodist church in my youth, when a rather bad visiting preacher inveighed against the splitting of the atom by quoting Genesis: “What God has joined together, let no man put asunder.” On his logic, chopping vegetables would be out, too!

Thanks, as always, Jon, for your nuance, calling me back down to sober appraisal.

I appreciated how you dealt at some length with the Romans 8 passage in your chapter 3, because that does seem to be the elephant in the room –perhaps no less elephantine for its singularity in Scripture. At least I can imagine the major reformers happily hanging their hats on that one peg that I could imagine them defending as still being solid enough in its own right.

It seems a major part of your interpretive strategy in dealing with that passage is to note that rational agency can hardly be ascribed to any of creation apart from humanity, and therefore ‘hope’ or ‘futility’ cannot be very well ascribed to other animals, much less non-living matter. But isn’t that itself a modern spin? We do find on the lips of Jesus the warning that should any disciples be silenced, the rocks and trees themselves will cry out their praises to their creator (echoes of similar psalms that would he would be affirming). As metaphorical as that no doubt was, it does seem to have been common habit to personify nature to make these points. Couldn’t Paul have been simply continuing that same habit of thought and speech?

Merv

Well, as you saw, I did finally come down on the side of personification of nature, v the popular early alternative of “the human creature”. But a metaphor, in the end, is still a metaphor – and I don’t think there was any real sense in the Scripture writers that they thought the trees really were clapping their hands, or that the stones had spiritual consciousness. Interestingly there seems far less personification of the animal creation in Scripture than the vegetable and non-living. Animals seem to given a much more limmited and realistic repsonse to God – eg they’re glad he gives them their food.

But remember, the common interpretation of Rom 8 goes beyond even consciousness to a nature bewailing its fall into evil (which is itself a weighted interpretation of “corruption”, which Paul commonly uses of material perishability rather than evil). If we granted nature these conscious feelings, it would still leave the question of whether it was bemoaning its fall (which the text doesn’t say) or its created tendency to change, whose human, spiritual parallel (the gift of eternal life) is the subject of the text.

Also it leaves the question of why God would “subject it” “in hope” if in fact it fell into evil as a shortcoming or, at most, a judgement.