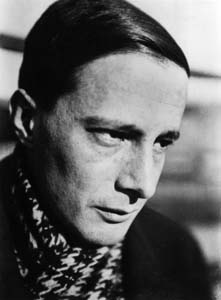

Michael Polanyi was one of the great polymaths of the twentieth century, contributing significantly to chemistry, philosophy, sociology and economics. He was also a devout Christian. His work included a thorough critique of the scientistic positivism of his age (raising its tattered standard again in the populist New Atheism in ours), arguing cogently for a far deeper and broader understanding of epistemology. A friend of Einstein and other great scientists, he wrote usefully on academic freedom too – again apparently foreseeing and warning against the political and ideological restrictions now seen in the research sciences.

Michael Polanyi was one of the great polymaths of the twentieth century, contributing significantly to chemistry, philosophy, sociology and economics. He was also a devout Christian. His work included a thorough critique of the scientistic positivism of his age (raising its tattered standard again in the populist New Atheism in ours), arguing cogently for a far deeper and broader understanding of epistemology. A friend of Einstein and other great scientists, he wrote usefully on academic freedom too – again apparently foreseeing and warning against the political and ideological restrictions now seen in the research sciences.

I’ve been aware of Polanyi for many years, but never actually read him. But he has things to say that relate to what we’ve been exploring on The Hump in relating science to the orthodox Christian doctrine of creation, and this is summarised in his 1968 essay here.

After reading and chasing links it I became aware of the controversy that led to the closure of the Michael Polanyi Center for Intelligent Design at Baylor in 2000, which episode has all kinds of unpleasant aspects associated with the culture wars over ID, of which I only want to touch on the fact that the heirs of Polanyi objected that he would not have supported Intelligent Design. That’s not of great import in the scheme of things (he was no longer around to ask, after all). But it does make it worth trying to pin down what he did believe, and why – and maybe daring to critique it.

Polanyi’s essay starts with the analogy of machines, pointing out how, though dependent on physics and chemistry, they are not reducible to them. There is a higher order organisation which he describes in terms of “boundary conditions.” This gives machines two separate principles of control: their operating physical laws and their boundary conditions, due to their design. At this point he makes the connection with information using the analogy of language, which contains a number of such heirarchical levels, each with their own “boundary conditions”:

All communications form a machine type of boundary, and these boundaries form a whole hierarchy of consecutive levels of action. A vocabulary sets boundary conditions on the utterance of the spoken voice; a grammar harnesses words to form sentences, and the sentences are shaped into a text which conveys a communication. At all these stages we are interested in the boundaries imposed by a comprehensive restrictive power, rather than in the principles harnessed by them.

Now in effect, Polanyi is describing Aristotelian form (as at least one of his commentators points out), and is making the same correlation of form/boundary conditions with information that I have previously made in discussing formal causation. Life too, he goes on, is under “dual control”; physiology, like the machine’s design, constituting a higher level of organisation not reducible to physics and chemistry. He extends this argument as he examines life in the context of DNA. Like Hubert Yockey then and ID theorists now, he draws on information theory, showing how DNA’s very effectiveness as an information-carrier depends on its not being determined by physics and chemistry. Working on the (now partly outdated) assumption that development, too, is under the control of DNA, analogously to the machine’s engineer, he demonstrates that each organism is the product of a higher-order organisation than that of basic laws, though not conflicting with them. And that organisation, as shown by experiments like the regeneration of embryonic sea-urchins, is a holistic “integrative power”, which he compares to a “field.”

Polanyi extends this idea to a whole system of irreducible heirarchies in living things. He compares the hierarchy of voice, vocabulary, grammar, style and content in spoken communication (none of which is in the least determined by the lower levels), to the levels of the vegetative, active, intelligent and rational (very much as in Aristotle) in life. In each case the higher level cannot be defined by the lower.

How does he envisage the coming into existence of these levels? Essentially, he is an early example of the “emergence” theorists represented in our day by those like Stuart Kauffman, Denis Noble or Michael Denton (and possibly even Simon Conway Morris): that organisms become, by a kind of apprehension of something innate in the natural order, greater than the sum of their parts.

It’s important to understand that to Polanyi this can only take place because of the prior existence of such higher orders in some other realm – in other words, he sees them, though natural, as pointers to a God at least as rational as we are who created the system. By way of illustration, he denies the ability of the natural selection of random variations to produce new boundary conditions. Specifically, he points out (astutely) that though selection itself may be said to be non-random locally, in the sense of being, in effect, an organised environment acting (in philosophical terms) teleologically on random variations to produce further adaptation, this situation changes when evolution is viewed globally. This is because the environment itself is varying randomly (through climate change, vulcanism asteroid strikes etc): random mutation plus random environment cannot possibly consistently produce higher levels of organisation, and certainly not the overarching trajectory of life.

So although he is working in the realm of science, this is also a philosophically-based and theologically-charged view of life. How does it differ from Intelligent Design, then? I would argue that it is actually quite compatible with the basic tenets of ID, in that it postulates a finely-tuned natural system in which the “boundary-conditions” that emerge point to a Creator who has at least these attributes, just as cosmic fine-tuning does.

But it differs from most ID in being concerned with levels of operation rather than with specific designs – if you like, God must be a communicator to enable all the levels of language to which Polanyi refers, but didn’t write the book himself. Accordingly organisms that “plug in” to a higher level of organisation evolve “freely” at that level. So the Creator creates nothing individually (including man presumably), and no particular room is left for providence: it’s an essentially Deistic system. And this is my problem with Polanyi: for some reason he seeks a naturalistic, if ultimately Christian, solution, even though he never got more specific in suggesting how these “boundary conditions” might be written into nature, and even though to this day such emergent powers have not been found, nor do they show any great signs of being found.

In fact, there is recent work to suggest that a distinction Polanyi himself makes between inanimate systems of “boundary conditions” in geology, geography, and astronomy (which, he says, do not constitute “dual control”) and living systems (which do) cannot be breached in nature – ie that there is a profound difference between self-ordering and self-organisation, between a snow-flake and a bacterium.

Had he wished, Polanyi would have found an alternative model at hand. As I’ve said his “boundary conditions” are closely related to Aristotelian form, and he had the whole tradition of Thomist creation doctrine (amongst other historical streams) on which to draw to allow for God’s bridging of the boundaries he found in nature. After all, such activity would follow on naturally from his analogies: a machine has an engineer, and a speech an orator, so why not living organisms a Creator? His God was that of the Bible, after all, (though he was not a literalist or inerrantist):

Only a Christian who stands in the service of his faith can understand Christian theology and only he can enter into the religious meaning of the Bible. Theology and the Bible together form the context of worship and must be understood in their bearing on it… (Personal Knowledge, p281)

The Bible makes the same “engineering” and “authoring” analogies overtly in its pictures of God the potter and the Lord who creates by his word – indeed, even by Christ, his Logos. Why, then, did Polyani opt for an imprecise and speculative process of emergence as God’s means of creating life?

Well, in the first place his ideas arose originally from Gestalt psychological theory, in which emergence is prominent (having its roots in Enlightenmenet thinkers like Hume, Goethe and Kant). It appears to me he may have also been influenced theologically by the prevalent “mere conservationism” I mentioned in my previous post, and also by the modernist scientific and theological zeitgeist (he was for a long time a fan of Paul Tillich), and particularly by its supreme self-confidence that Neodarwinian evolution had done and dusted the question of life. The theological decision towards conservationism, as I said in the last article, predisposes one to Deism and naturalism: indeed, it makes any divine action problematic scientifically and even morally. On the science side, note a couple of passages in his essay related to mechanisms:

In the light of the current theory of evolution, the codelike structure of DNA must be assumed to have come about by a sequence of chance variations established by natural selection….

…But there does exist a rather different continuity between life and inanimate nature. For the beginnings of life do not sharply differ from their purely physical-chemical antecedents. One can reconcile this continuity with the irreducibility of living things by recalling the analogous case of inanimate artifacts. Take the irreducibility of machines; no animal can produce a machine, but some animals can make primitive tools, and their use of these tools may be hardly distinguishable from the mere use of the animal’s limbs.

The first paragraph here assumes that the origin of DNA is not problematic for evolution: yet it is that very achievement which led Eugene Koonin to propose the many-worlds multiverse as the only way of lessening the impossible odds to something more realistic, and which led the father of information theory in evolution, Hubert Yockey, to consider the origins of DNA as a code to be scientifically intractable in principle.

Similarly the second paragraph (perhaps Polanyi was misled, like so many modern students, by the Miller-Urey experiments) takes the origin of life to be a simple chemical step from spontaneously formed amino acids to a simple LUCA. I wonder how he’d have responded to the case made in Stephen Meyer’s Signature in the Cell?

I suggest that taking away these easy assumptions about OOL and evolution’s simplicity leaves one in dire need of a miracle. Dispensing with mere conservationism makes such a miracle – or even lesser acts of providence – unproblematic theologically. I’ve no idea if those are steps Polanyi would have been willing to take in different circumstances. But I do raise them as throughly plausible alternatives to what I see as the weak points in what, overall, is Polyani’s very strong case for theism against materialism.

Jon,

I welcome this discussion – Polany and Dobzhansky are two examples of prominent scientists who also addressed aspects of evolution that impacted on their religious beliefs.

Polany’s major premise may be summarised in his statement, “The principles of mechanical engineering and of communication of information, and the equivalent biological principles, are all additional to the laws of physics and chemistry.” Yet can we articulate such principles as scientific statements?

Dobzhansky, on the other hand, has quoted Chardin, “Is evolution a theory, a system,

or a hypothesis? It is much more it is a general postulate to which all theories, all hypotheses, all systems much henceforward bow and which they must satisfy in order to be thinkable and true. Evolution is a light which illuminates all facts, a trajectory which all lines of though must follow this is what evolution is.” Dobzhansky also concedes that many scientists would not share this expansive view of Darwin’s thinking, and also understands that a great deal is unknown in the bio-sciences.

It is indeed intriguing that the views of the Sciences have motivated prominent scientists to examine the bio-sciences within such a Universalistic framework. One outcome of this activity has been to force many scientists to think outside of their disciplines – it is in this context that I also find myself asking many questions, including the obvious ones, such as, “If scientists honestly bring such expansive views, they should have answers to fundamental questions that are inherent in such outlooks, such as how life began, why DNA could contain such a staggering amount of information, the problem of optically pure isomers, (to mention a few) and how these scientists have provided a rational and testable (and universal) hypothesis on these fundamental questions. People such as Polany and Dobzhansky are quick to point out the many difficulties and shortcomings in such a universal outlook, which attests to their intellectual honesty. However, the more (as a scientist) I read of current evolutionary outlooks, the more I find (not less) a horrendous blending of aspiration/wishful thinking, with the results of research which are much more limited, and cannot support such a universal outlook. For example, I have also come across papers that show (a) natural selection is ineffective and may not be classed as a mechanism, to (b) natural selection is absolutely true and it explains everything, from selection of primordial ‘life’ to the presence of all life in the past, the present and the future. Science cannot accept both (a) and (b), and less charitable people may regard this as another contradiction within Darwinism.

I submit scientists who have become so enthused by Darwinism have left forgotten the ‘disinterest’ that the scientific method requires of us, and are indulging in a non-scientific conflict that in the end will reflect badly on the sciences. It is imperative that all scientists display the self-discipline required from them, and state clearly (if they are able) a distinction between testable ideas and theories, from speculation and wishful thinking that at times is simply wildly unscientific. Perhaps all of their wishes regarding Darwin’s outlook may, at some point, be proven to be scientifically sound – or perhaps they may not. Scientists may wait for such a day; otherwise they are indulging in very unscientific “prophesying” for their “apostle” Darwin.

Let us use a current example that has worried TEs – Adam and Eve. Instead of putting the burden on Biblical accounts on this matter, it is very reasonable that a ‘burden of proof’ be placed on those who claim they have a scientific basis for re-interpreting, or discarding, the Biblical account. Scientifically, they would be required to either provide the physical remains of Adam and Eve, and from these remains, make scientifically valid statement or provide data to support any hypothesis they propose. Inferring this and that, and then deciding what Christian doctrine should be, is frankly banal and wacky. It is too easy for people to slip from, “science has shown” to “I am a scientist and now I can proclaim anything I wish”. I am not suggesting that most, or all scientists, do this consciously, but at some level, even competent chaps such as Polany and Dobzhansky, and many at Biologos, may slip into this error. My comment is to point out the discipline required of us by science. At the very least, they should state they are not speaking as scientists, but putting forward their opinion, which everyone is entitled to so do.

Thanks GD

The Universal Darwinism you describe has, for me, one overwhelming characteristic, which is lack of humility. I’m not a working scientist, but spent an entire career in a scientific discipline, and like you the more I read the more I see we don’t know.

In that context, to take one simplistic, intuitive idea and apply it as a universal acid isn’t even religious – it’s superstitious. It’s not just the life sciences modelling genetics by our crude measures and then offering blanket denials of Adam and Eve (it would not be so bad if they merely suggested re-examining what the doctrine means); but biblical scholarship taking, as it were, one data point and the origin and offering a straight-line graph as authoritative.

Polanyi at least, it seems to me, is willing to take an expansive view of what existence is under God: it just seems to me that he picked up rather too much of the “Now we know…” scientific trope that he successfully critiqued in the positivists.

I am particularly drawn to Tertullian’s statements:

“Reason, in fact, is a thing of God, inasmuch as there is nothing which God the Maker of all has not provided, disposed, ordained by reason—nothing which He has not willed should be handled and understood by reason. All, therefore, who are ignorant of God, must necessarily be ignorant also of a thing which is His, because no treasure-house at all is accessible to strangers.”

And

“For if God is wise and powerful (which even they who pass Him by do not deny), it is with good reason that He lays the material causes of His own operation in the contraries of wisdom and of power, that is, in foolishness and impossibility; since every virtue receives its cause from those things by which it is called forth.”

Tertullian, although he wrote so early (or maybe because he did) understood that reason is definitionally the nature of God, and that humans show, at best, a poor reflection of it. He also had a broad understanding of what reason itself is. Moderns, in contrast, have grown up in the restricted Enlightenment understanding of reason as a human quality by which all things – even God – are judged. And a very restricted idea of reason it is at that.

Roger Scruton has written an excellent piece in New Atlantis, in which he shows how such “reason”, in the form of scientism, actually seeks to explain away what it should be trying to understand – which means all that is most significant in the world. He writes:

I wouldn’t disagree with that at all.

Scruton (and others such as Fuller) provide a useful perspective – my only comment(s) is to question the implied assumption that people such as Dawkins (and other such public nuisances) are legitimate representatives of science. I find such an outlook offensive; these people have gone way out of their particular discipline, and assume the mantle of the Sciences, and act as if they are self-appointed spokespersons for Science (or Natural Sciences); I find it odd that these applies to people in the Arts, Humanities and Theology; I am still astonished (after a couple of years of involvement in Biologos and one or two other sites) of what appears as a general acceptance of Dawkinism (?) and the ways he represents Science (at least on the internet and the media).

I find criticisms of scientific outlook very helpful, especially from people involved in philosophy of Science – those of us who have not made a career of becoming a public nuisance, are aware that as we specialise our thinking becomes increasingly narrow, and we are critical of usually a very small segment of science, and little of general matters. I guess as controversies continue, and with Science conscripted for ideological activities, more scientists (hopefully) will take time to consider the general sphere of human activity and perhaps object to how Science may be misused in such.

GD

I wouldn’t say that Scruton regards scientism as legitimately representing science, but it does seem prevalent – as you say, even to some extent in the narrowness of vision of those on BioLogos.

Where is the discussion of science there beyond doctrinaire (and basic) Neodarwinism? Never a squeak do we hear about ENCODE, Shapiro, Jablonka, the extended synthesis, etc, etc. And where is the discussion of theology beyond abandoning whatever historical doctrine doesn’t immediately accommodate itself to the Neodarwinism, naturalistically understood?

More widely there seems to have been a kind of straightjacket applied to scientists, when you compare their discourse today with the philosophically literate people like Polanyi, Bohr, Heisenberg, or Einstein. Or even Gould, come to that.

There are a good many Christians and others with a broad outlook out there – including Nobel prizewinners. But it’s almost as if they’re afraid to speak frankly about their views, particularly on evolution – quite unlike the open dialogue of a century ago. I can’t say I’m surprised, seeing the storm of disapprobium from the defenders of the True Faith when they do.

Whatever the reason, the public perception of science, and its teaching, have never been more monolithically materialist. In that sense Dawkins and co have been victorious, even as their intellectual castle falls about their ears. But I don’t somehow think it can last – the danger is that society will reject science altogether because of the arrogance of its high priests – which Steve Fuller, in particular, seems to predict.

Thank you, Jon for this piece on Polanyi.

I want to follow up on part of GD’s comment from way above.

GD wrote:

“I submit scientists who have become so enthused by Darwinism have left forgotten the ‘disinterest’ that the scientific method requires of us, and are indulging in a non-scientific conflict that in the end will reflect badly on the sciences. It is imperative that all scientists display the self-discipline required …”

Or maybe this is setting the bar too high for what science can be? Galileo dogmatically stuck to his favorite pet [Copernican] theory even as it was starved for any actual evidence, and indeed in the face of scientific evidence against it. Einstein famously replies when asked what he would have done if the universe had not been like his beautiful theory predicted, that the universe [or God] should have then been in error (or words to that effect). That these scientists happily (or accidentally) ended up being right –and are rightly celebrated for it. Many more are wrong, but they are wrong no less dogmatically. It isn’t the situation your high school science texts put forward as model science.

Nor should it be, I think. Scientism would have us see science in such glowing terms but real life shows us a much messier picture, especially on the ‘micro’ scale of individual scientists’ lives. It may seem a little more cleaned up if we back the view out a bit and see how some wrong ideas get [eventually] corrected, but even at this scale we have no crystal ball to tell us which presently persisting scientific dogmas will themselves face a withering light of some new day. So we have no boundary we can easily apply while stating “the mess shall not pass here.”

Merv – Let us then agree to teach the controversy! 🙂

As long as one doesn’t insist that all assertions are on equal footing (or ‘dis-footing’ as the case may be here). Dark energy, natural selection, and Boyle’s law are not at this time surrounded by identically sized clouds of uncertainty. Some are still obscured behind impenetrable fog, but we mathematically imagine their existence/operation. Others we think we see in crystal clear light. But even on the simplest laws we can never quite claim 100% freedom from controversy. Flat-earthers are still out there. I hope I can be pardoned for spending very little [no] time on that ‘controversy’.

Merv,

By and large, scientists make clear statements on ‘levels of uncertainty’ – thus one Noble prize recipient, when asked on dark energy and matter, described himself as ‘militant agnostic’, and another stated ‘very uncertain’. You rarely find scientists providing opinions that range from very certain to totally uncertain on say, dark energy. This is not the case with things such as natural selection – the large range of opinion on this should make everyone scratch their head. An apologetic approach has been given by some atheists (and curiously not from what I have read from TEs), in that Darwin’s theory is semantic, and thus may suffer from a ‘wide ranging’ interpretation. Be that as it may, it should not be taught and discussed as something that is clear and ‘done and dusted’. The quote I used above shows that some consider that as above done and dusted, and ‘all science thinking should bow to Darwin’s outlook’. This is hardly a question of an equal footing, or such like.

And I don’t think of N.S. as being “done and dusted” either. You may have noticed the order I listed those three. That was on purpose, since I think it should be fairly uncontroversial to suggest that N.S. probably has more known about it than dark energy, but is not as thoroughly explored as something like Boyle’s law. Granted, that’s a huge range of uncertainty for people to happily kick N.S. around in. But my wider point was just that the range exists, and I teach accordingly.

I risk making this discussion more about semantics than substance – I would say that more is stated, believed, inferred, guessed and ‘waffled’ about N.S. than dark energy, Boyle’s law, and probably most other areas of science (this is more likely when we consider N.S. and evolution extended into the arts, humanities and sociological sciences). There is disquiet from a minority of scientists and others, for the obvious reason – Darwinian thinking has been given a privileged position and this has now become all pervasive, especially in activities we would describe as public presentations. The scientific basis for this does not exist – I have often stated that we can do all physical scientific research without referring to Darwin. I do not think many (if anyone) teaches this state of affairs; if this were the case for any other area of science, we would have ‘riots in the streets of academia’.

A case in point, GD – regarding at least the blanket Darwinisation of public life. There’s a story on BBC news this morning about elephants being able to distinguish between Massai and some other local language, being disquieted by the former because, it seems, they’re the people who tend to poach elephants for ivory.

The BBC interviewer of the scientist expresses admiration and surprise: “So they’ve evolved to be able to tell the languages apart!”

Now, whatever the mechanism is – and the most obvious one is intelligence + learning, and maybe more mysterious cultural transmissionan, the evolutionary one is amongst the most implausible. It would involve a mutation for speaking Massai being selected or something equally nonsensical. Yet it’s the first port of call because every darned thing in biology is attributed to this all-provident deity. Incidentally, the scientist in the interview didn’t venture to gainsay this explanation.