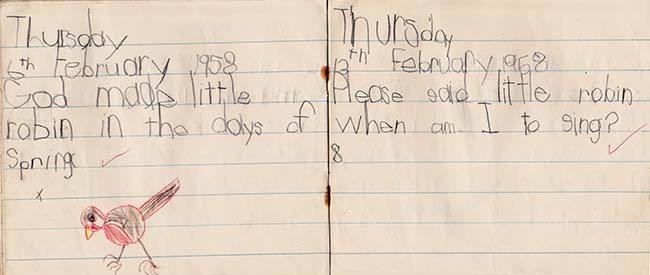

How the human mind develops concepts is a wonderful thing. My mental schema for that most iconic of British birds, the robin, is built upon the foundation a song I learned from Miss Jerome (a wonderful teacher) for my first Christmas at school. Apart from an even more juvenile nursery rhyme involving cold north winds and what Robin does when they blow (poor thing), it was possibly my earliest exposure to the bird, maybe even pre-dating my seeing it in the feather.

The song went:

God made little Robin, in the days of spring,

“Please,” said little Robin, “when am I to sing,

when am I to sing?”God then spoke to Robin, “You must sing always,

but your sweetest carol keep for wintry days,

keep for wintry days.”God heard Robin singing, such a merry song,

“Cheer up little children, summer won’t be long

Summer won’t be long.”(Florence Hoatson 1881-1964)

I suspect that Miss Hoatson’s theological source was unreliable, but her poem reflects pretty accurately both the warmth of feeling towards this bird in Britain, and its positive representation in folklore. I must point to out to foreigners that England’s Robin differs from both the Transatlantic and Antipodean creatures of that name. Originally called just “redbreast”, he acquired his personal name “Robin” in the fifteenth century. Probably this was largely due to his habits both of approaching people as they worked, and nesting inside their important buildings, especially barns and churches.

Robin’s familiarity with humans results from of his insectivorous habits. For some reason he’s acquired the habit of hopping around large mammals as their hooves disturb the soil, and that includes the workman digging his garden – hence the common image of the bird perching on a spade. One old belief was that robins would gather leaves to cover bodies about to be buried.

Robins also, as Miss Jerome’s song taught me, sing sweetly during winter (and even when night is falling and the other birds fall silent).

Robins also, as Miss Jerome’s song taught me, sing sweetly during winter (and even when night is falling and the other birds fall silent).

That, and the nicknaming of Victorian postmen “robins” on account of their red coats led to the birds becoming a popular image on Christmas cards to this day.

The kindly feelings towards robins led to the saying that, with swallows, they were especially beloved of God and to harm them unlucky, a belief that carried over into William Blake’s poem Auguries of Innocence of 1803:

A robin redbreast in a cage

Puts all heaven in a rage

That whole poem is a thought-provoking juxtaposition of the goodness of God’s creation with human evils, showing how nature can be an agent for a deeper understanding of moral truth. My own education after Miss Jerome, however, somehow neglected Blake, but included another folk-song:

Who killed Cock Robin?

“I,” said the sparrow

“with my bow and arrow,

I killed Cock Robin.”

Actually the more more likely culprit would have been another robin, for they are notoriously belligerent towards their own kind, and even to other small birds –  territorial aggression accounts for maybe 10% of adult deaths, which attrition is no doubt just as selectively advantageous as the long-tailed tits I mentioned on another thread that, instead of killing their neighbours, assist them in raising their brood if their own nest is predated. In evolution, what is good for the goose appears to be bad for the gander. The mutual aggression of robins, though, was noted as long ago as their friendliness towards God and man. Andrea Alciato’s Emblemata, published in Paris in 1584, has the proverbial: Unum arbustum non alit duos erithacos (You won’t find two robins in one bush).

territorial aggression accounts for maybe 10% of adult deaths, which attrition is no doubt just as selectively advantageous as the long-tailed tits I mentioned on another thread that, instead of killing their neighbours, assist them in raising their brood if their own nest is predated. In evolution, what is good for the goose appears to be bad for the gander. The mutual aggression of robins, though, was noted as long ago as their friendliness towards God and man. Andrea Alciato’s Emblemata, published in Paris in 1584, has the proverbial: Unum arbustum non alit duos erithacos (You won’t find two robins in one bush).

An old folk tale links the robin to the crucifixion (not geographically impossible, the bird being known as a passage migrant in Israel). The robin in question is said to have removed a thorn pressing into Christ’s brow from the the crown he wore, the blood staining his breast and, of course, those of his descendants. This legend was extant in both Brittany and Wales – and so probably dates back to Celtic Christianity, with its renowned reverence for the natural world.

In fact one of the oldest robin tales is directly attributable to that source. St Leonor was a French evangelist to Armorica in Brittany in the early sixth century. In legend he is said to have followed a robin with a grain of wheat in its mouth to an overgrown (presumably Roman) farmstead where a few heads of grain were growing. He had his people plant these, and two stags also emerged from the forest to assist with the ploughing. The local people thus re-learned the farming they had forgotten. The Celtic Christian appreciation of nature is obvious, but it appears a totally tall story.

Yet American author and poet Sidney Lanier, in his book Music and Poetry, says truth comes in many forms, and that this is actually a story about science.

The birds and stags are terms of poetry. But notice, again, these are not silly, poetic licences; they are not merely a child’s embellishments of a story; the bird and the stags are not real, but they are true. For what do they mean? They mean the powers of nature. They mean, as here inserted, that if a man go forth, sure of his mission, fervently loving his fellow-men, working for their benefit… – presently he will succeed; for the powers of Nature will come forth out of the recesses of the universe and offer themselves as draught animals to his plough.

If Leonor actually returned a population fallen into poverty and barbarism after the withdrawal of the legions to a productive agricultural relationship with nature, isn’t the story of the robin and the stags as memorable and appropriate an image as any?

You may wonder why I’ve been meandering through mythical and less-mythical references to a small European bird. The reason is that, within 24 hours this week, I saw evidence of the superb natural abilities of this familiar friend. The first was as I went to feed our chickens, when I noticed a tiny movement in a patch of earth by a fence-post. It was a mole, an uncommon visitor to our spread, about his early-morning business of excavation. I had only noticed his presence by chance – but I saw that our local robin was already well aware, and was hopping about waiting for his share of worms and grubs.

The second was this short video by a physicist, Jim Al-Khalili from our own reader Ian Thompson’s old department at Surrey University.

That robins should navigate across continents by a protein in their eye which creates a pair of quantum-entangled electrons is remarkable. But note towards the end that Dr Al-Khalili reveals his physicist’s want of imagination – one might call it is his “personal incredulity” – by saying the mechanism is “nothing short of a miracle.” Had he been a biologist he would have understood evolution, and known that such a quantum-savvy protein and such an elegant application of it is, like the robin’s sharp eye for a mole, readily explained by random mutations, fixed either by neutral drift or by natural selection.

We are, after all, far removed from the implausible world of Florence Hoatson.

Footnote: Jim Al-Khalil, it turns out, is the president of the British Humanist Association (a small sect of only 28,000 members, compared to my own minority Baptist denomination of around 140,000), who has today signed a public letter berating the Prime Minister for his contention that Britain should be proud to be a “Christian country”.

I suppose that make little Robin’s quantum navigation “nothing short of an official humanist miracle.”

Further footnote:

Alerted by my wife this morning to a massacre at our robin nest-box in the hay store. On examination, nest box undisturbed and brood evidently fledged and gone, but two dead adult robins in close proximity shoing only minor damage. My conclusion: probable mutually assured destruction from territorial dispute, as per OP.

This clearly overturns the “nothing short of a miracle” business of quantum navigation, shows that the loving God of Christianity could not possibly be involved in robin-life and demonstrates that their genome must in fact be random junk. Where’s your designer now? (and blah, blah, blah)

Jon, quite a lot of the Y chromosome needs to be random junk, so we genetic genealogists will have neutral markers to figure out where our ancestors came from and who we are and are not closely related to. And the good souls at the Genographic Project need lots of neutral markers all over the autosomes to figure out past population movements. The randomness was clearly designed for us. 🙂

Wouldn’t non-random junk (or random non-junk) be an equally good marker? In any case, the junk in my robins’ Y-chromosomes seems to have made them peevish unto death.

Whatever makes robins aggressive presumably isn’t junk – it’s providing some hormonal/neural behavioral function that has worked out well for them. Sex determining genes are generally switches that turn lots of other genes on and off, and those other genes may be all over the genome. Most of the mammalian Y doesn’t do anything, but there are some important functions there in addition to the male determining gene SRY (2 papers in this week’s Nature.) I’m not sure if they’ve found the bird sex determining gene(s) or not. I know they were still looking a few years ago.

Markers wouldn’t have to be neutral just to serve as markers, although if they’re selected against, they would never reach useful frequencies as markers. (No one’s going to mess with a marker that occurs in 0.00001% of the popul.) If you want to estimate how old they are it’s nice to have a class of mutations, like most SNPs, that accumulate at a sort-of constant rate.

Right now my friends in the U106 (a big Y haplogroup in European men) Project are counting up SNPs that occurred after the U106 mutation in a 10 million bp subset of the Y that you can now get fully sequenced if you are willing to part with $750. (Too rich for my pocketbook. 150 of them have done it.) They measure the SNP accumulation rate in this segment by looking at well documented genealogies (with dates) of guys who have been sequenced, and compare it to the rates that academics get by using archeological dating combined with sequencing. The current estimate is that this segment of the Y gets a new SNP about every 4 generations (120 yr.) So you can get a rough estimate of how old a particular mutation is by how many SNPs are “downstream” in the Y-tree. U106 seems to be 4000-6000 yrs old, but they’re will be recalculating for a few years. Sequencing of dated ancient DNA samples will provide a check eventually.