The discussion on God’s “magical” activity on a previous thread managed to jettison the theme of the thread, and the overall theme of the blog too, that is the doctrine of creation. But it’s actually worth devoting a post to the subject of magic, because in many ways it is a magical understanding of the cosmos that the biblical creation doctrine subverted.

The scholars find it quite hard to define “magic” adequately, and to distinguish it definitively from religion. But it’s probably even harder to distinguish it definitely from science (as I’ll indicate later), so everyone’s interests are served by the attempt.

Let me paint a broad-brush picture first. Magic is the effort to manipulate, or sometimes to supplicate, hidden (aka occult) powers that are believed to exist within the Universe. In contradistinction religion, as understood through Creation doctrine, holds that any truly hidden power exists outside the Universe, in God’s hands, and that humbly seeking his will is the only valid way of interacting with it.

Another parallel insight comes from the ideas we’ve recently covered from Owen Barfield. Barfield’s thesis in Saving the Appearances is that man’s early view of the world was personal, mystical and magical, and that humans were related to that reality sacrally.

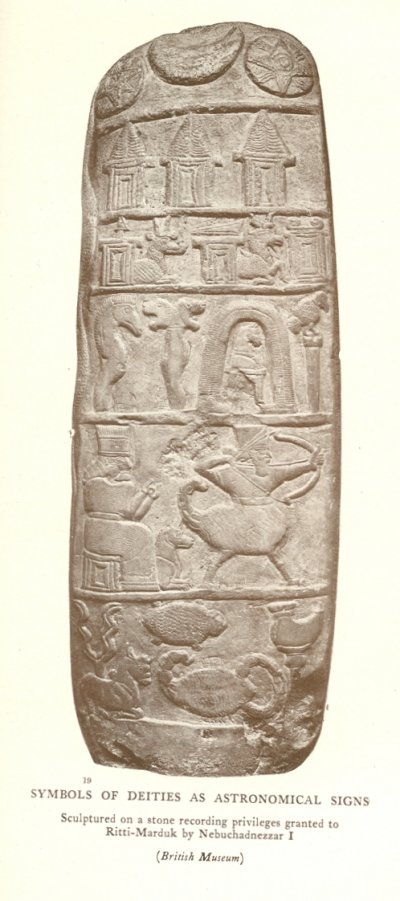

Consider what seeing the world as a personal being, of which we are all part, entails. It means that every part is intrinsically interconnected. In my body, the movement of my fingers corresponds to activity in every other organ – I act as a unity. That seems to play out in most versions of magic. For example, Babylonian astrology and divination were both intended to seek the will of the gods. But we must remember that the gods were, themselves, products of the cosmos and subject to fate as well. So Wikipedia’s article gives an example of an astrologer covertly damaging a dyke to substitute for an astrologically predicted flood, explaining:

Consider what seeing the world as a personal being, of which we are all part, entails. It means that every part is intrinsically interconnected. In my body, the movement of my fingers corresponds to activity in every other organ – I act as a unity. That seems to play out in most versions of magic. For example, Babylonian astrology and divination were both intended to seek the will of the gods. But we must remember that the gods were, themselves, products of the cosmos and subject to fate as well. So Wikipedia’s article gives an example of an astrologer covertly damaging a dyke to substitute for an astrologically predicted flood, explaining:

An astronomical report to the king Esarhaddon concerning a lunar eclipse of January 673 B.C. shows how the ritualistic use of substitute kings, or substitute events, combined an unquestioning belief in magic and omens with a purely mechanical view that the astrological event must have some kind of correlate within the natural world.

The same article hints at links between such magic and a scientific approach:

Ulla Koch-Westenholz, in her 1995 book Mesopotamian Astrology, argues that this ambivalence between a theistic and mechanic worldview defines the Babylonian concept of celestial divination as one which, despite its heavy reliance on magic… “shares some of the defining traits of modern science: it is objective and value-free, it operates according to known rules, and its data are considered universally valid and can be looked up in written tabulations”.

Similarly, speaking of a much later age, another source writes:

The principle governing natural magic in the Western occult tradition is the great Hermetic axiom “As above, so below.” Every object in the material world, according to this dictum, is a reflection of astrological and spiritual powers. By making use of these material reflections, the natural magician concentrates or disperses particular powers of the higher levels of being; thus a stone or an herb associated with the sun is infused with the magical energies of the sun, and wearing that stone or hanging that herb on the wall brings those energies into play in a particular situation.

This is associated with the mediaeval idea of the “great chain of being” adapted from the Greeks, which in theology saw all things as a hierarchy of authority emanating from God, but in the magical tradition (which essentially came back to Europe through the Hermetic writings in the early Renaissance) was seen in terms of the occult influence of the heavenly bodies being reflected in the events experienced on the lower realm of earth.

There are various contemporay classifications of early-modern magic, but the broadest is perhaps the division between natural magic, as above, and ritual magic, in which personal powers of demons and spirits were invoked. You can see how in the ancient world (eg amongst the Babylonians) the distinction was not clear – the gods and lesser spirits were inextricably bound up in what the stars, or the omens were doing, anyway. In European practice too the distinction between natural and ritual magic was blurred: spells, incantations and words of power were used in both.

A quasi-religious aspect became, if anything, greater in Christian countries because spirits were not value-free – one knew one was invoking satanic rather than angelic beings. Indeed, way back in Roman times magicians often pronounced the Jewish Divine Name as an especially powerful one, and even in Acts we read of Jewish exorcists co-opting the name of Jesus in the same way and suffering for it. But in the Bible the only word of power is God’s dabar – identified with Christ himself as the Logos in the New Testament.

And maybe that’s why Elijah, calling fire from heaven in a supernatural display of Yahweh’s reality and Baal’s non-entity, yet had subsequently to pray earnestly before God sent the rain he had promised: Elijah needed to be reminded that a faithful prophet is not a powerful magician, but utterly dependent on God.

So despite the sometimes confused interaction with late mediaeval and early modern Christianity (like Popes wanting their horoscopes cast!) one can see that the mindset behind early modern magic was essentially similar to that of the Babylonians.

In contrast the Genesis creation story is a radical, and revolutionary, departure from that ancient worldview. One obvious point is the way that the sun and moon, key players in the ANE in both religion and astrology, are simply called “greater and lesser lights”, to emphasize their placement by God for their functions in the world – and especially on man’s behalf. God is the sole power, and all that he makes is for his purpose, and answerable to him alone. And the stars serve, rather than ruling, man’s affairs.

Hebrew creation teaching is sometimes seen as a disenchantment of the universe. Certainly it’s both a de-divinisation and a de-personalisation of nature. But more importantly it’s a teaching about the individual diversity of nature, and a denial of the idea that we are all “just cells in mother earth’s domain.” The Universe is not just one being, each of whose parts are subsumed to its endless cycles of repetition. In one sense, the inhabitants of God’s Creation are his “artifacts”, each different, each accountable in its own way to its particular concerns and, ultimately, to God. He expresses his own creativity and multifaceted being through the diversity and contingency of creation. Such an idea was, and is, completely revolutionary.

Moreover, God deals directly with each part of creation, even when he institutes intermediate order and function, for example, in “laws of nature”. The stars do not govern us, nor the entrails of sheep. Rather, what happens to all is between each and its Creator. There may well be spiritual beings in the cosmos as well as physical animals and the uniquely animal-divine being that is man. But they are his servants (or, it seems, sometimes his rebellious servants), and are not beings to be appeased, supplicated or manipulated in their own right.

So when Leviticus and Deuteronomy prohibit divination, seeking omens, mediums who commune with the dead and spell-casters, it is not simply one cult defending itself against its rivals. Israel were called to be free from fatalism and to know what it means to be God’s own people, in creative relationship with their maker – and with all the other entities he has made, which are wonderful not because they rule us or have secret powers, but because they are all the provision of an infinitely creative Father. This clear demarcation of magic from faith is reflected in the mockery of the prophets, too. And so Isaiah speaks against necromancy because Israel has the word of the living God himself:

When they say to you, “Consult the mediums and the spiritists who whisper and mutter,” should not a people consult their God? Should they consult the dead on behalf of the living? To the torah and to the testimony! If they do not speak according to this word, it is because they have no dawn. (Isa 8.20)

And later he ridicules natural magic too:

Stand fast now in your spells

And in your many sorceries

With which you have labored from your youth;

Perhaps you will be able to profit,

Perhaps you may cause trembling.

You are wearied with your many counsels;

Let now the astrologers,

Those who prophesy by the stars,

Those who predict by the new moons,

Stand up and save you from what will come upon you.

Behold, they have become like stubble,

Fire burns them;

They cannot deliver themselves from the power of the flame (Isa 47.12-14)

And the reason?

I am God, and there is no other.

I am God, and there is none like me.

I make known the end from the beginning,

from ancient times, what is still to come.

I say: My purpose will stand,

and I will do all that I please. (Isa 46.9-10)

Even this polemic against idolatry (see Barfield for how idolatry arises from the magical wordldview) is ultimately about true relationship:

Even to your old age and grey hairs

I am he, I am he who wiull sustain you.

I have made you, and I will carry you:

I will sustain you and I will rescue you. (Isa 46.4)

And so the reason that the mediaeval Church, from Patristic times onwards, disapproved so much of magic was not solely because it was untrue – though that was a factor. It was because magic’s determinism denied both God’s sovereignty and people’s freedom. One might add that even nature was bound into a denial of its diversity under God by magic. The Church’s stance was not “anti-superstitious” (which is a modern category), but anti-fraud (eg regarding the supposed malevolent power of witches), anti-obscurantist (regarding the occult powers of natural magic as distinct from nature’s manifest powers) and anti-satanic (regarding ritual magic).

Now let’s turn to the links of magic to science, which paradoxically it helped to launch for about a century. As Brian Copenhaver writes:

Around 1600, some reformers of natural knowledge had hoped that magic might yield a grand new system of learning, but within a century it became a synonym for the outdated remains of an obsolete world-view.

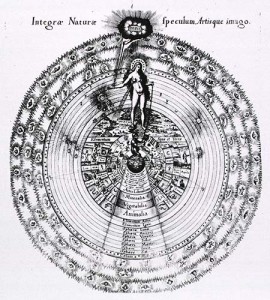

Illustration from physician Robert Fludde Anima Munde (1617-21) of the oneness of nature. Kepler disputed this with him in a famous correspondence.

One influence on this was a writer called Agrippa, who wrote a “notorious” handbook of magic De occulta philosophia, which circulated amongst the intelligentsia in manuscript form from about 1510, and remained influential though Agrippa later wrote a recantation of magic in favour of true faith.

Agrippa’s occultism was of great importance for natural philosophy because of its account of natural magic, which he described as the pinnacle of natural philosophy and its most complete achievement…

“With the help of natural virtues, from their mutual and timely application, it produces works of incomprehensible wonder…. Observing the powers of all things natural and celestial, probing the sympathy of these same powers in painstaking inquiry, it brings powers stored away and lying hidden in nature into the open. Using lower things as a kind of bait, it links the resources of higher things to them … so that astonishing wonders often occur, not so much by art as by nature.”

Francis Bacon “Sylva Sylvarum” According to Spedding: “a considerable part of it is copied from the most celebrated book of the kind, Porta’s Natural Magic” http://www.faculty.umb.edu/gary_zabel/Courses/Phil%20281b/Philosophy%20of%20Magic/Natural_Magic/jportah.html

Agrippa’s book reflects entirely the “chain of being” mindset already described. The knowledge magic promised was a great inducement to natural philosophers working on astrological or alchemical magic, and consonant with the emerging ideas of those like Francis Bacon, who advocated the painstaking interrogation of nature for her secrets – those secrets being in large measure conceived as occult powers.

It’s not so much that occasional natural philosophers, like Newton, retained an interest in mediaeval magic superstitions, but that, for a while, an early-mdern revival of classical magic was a major impetus for natural philosophy. The experimental nature, and careful record keeping, of natural magic (you can get a feel for this from the Canon Yeoman’s Tale in Chaucer) was adopted by the natural philosphers intent on taming nature to human ends.

How then, did magic get sidelined? In the first place, because it simply didn’t work, and in the second because the experimental method began to produce genuine results of its own. It would seem that part of the reason for this was the genuinely religious sentiments of many of the new generation of natural philsophers like Robert Boyle, Galileo, Kepler and Newton himself, whose ideas were deeply rooted in creation theology (“thinking God’s thoughts after him”) and to whom the assumptions of natural magic became increasingly uncomfortable. That’s why Kepler’s day job was casting horoscopes, whilst his real passion was the Pythagoran order of God’s wisdom in the detailed movement of the planets. And it’s why Newton’s rather eclectic mixture of mathematics, magical speculation and secret Arianism seems so anomalous to us – it was inherently unstable.

One thing clearly missing from the historical reviews of this fascinating period is any clear example of a great natural philosopher without some kind of supra-natural metaphysical foundation for their work. There’s nobody who writes, “Just give me the facts, and leave the metaphysics out of it.” Rationalistic Materialism was the product of a later age, built on the foundations, in part, of natural magic.

But has occultism, even now, been completely replaced in science? After all, what is Newton’s gravity but the occult action of the heavenly bodies on even earthly affairs? Has anybody a clear idea of what gravity actually is, apart from a distortion of the even more occult space-time continuum? Magicians often produced illusions using lenses – which is why some of Galileo’s opponents weren’t too impressed by his telescopic discoveries. Now, very much of our science is only discernible because of instruments that few people understand.

Let me end with another provocative quote from Brian Copenhaver’s work: perhaps it would be helpful to unpick, in any discussion, just where the real difference between science and magic lies – it’s far less straightforward than one would suppose:

The corpuscles theorized by Robert Boyle (1627-91), though endowed with picturable properties of size, shape, and motion and redefined as primary qualities, were just as hidden as occult qualities and no more observable. Boyle argued that observable properties emerged only when these least bodies aggregated in structures; however, the resulting secondary qualities, such as color or odor, were not the scholastic entities that Molière mocked and Boyle found incomprehensible. Never entirely escaping the world of magic, Boyle improved on occult qualities by replacing them with other indiscernibles, tiny bodies to which he imputed properties like those of ordinary objects…

By reducing causality to structure, Locke and Boyle brought occult phenomena within the scope of the new science. Boyle even proposed a theory to cover action-at-a-distance and its unobservable agents. Rather than attributing an electrical property to amber in order to explain its power of attracting chaff when rubbed, he argued that this familiar but puzzling effect resulted from an effluvium, a structure of imperceptible particles with no properties but size, shape and motion. Agrippa had referred amber’s attractiveness to an occult virtue that was not only unobserved as anything distinct from its visible effects but also unlike anything otherwise observed. Although their smallest parts were ultimately no more perceptible than Agrippa’s occult qualities, Boyle’s effluvia had two advantages: an imputed structure made them seem concrete and intelligible; and an analogy with visible vapors brought them within range of everyday experience.

Jon, you can surely see that your definition of magic is only sensible if one accepts your theological view. That’s fine; this is a Christian blog and Christian scholars have every right to give a term a technical definition, just as biologists defining “bug” as an insect belonging to the order, Hemiptera.

But that doesn’t mean a more general definition of the term is wrong. From a secular point of view, it does not matter at all whether the to-us-imaginary supplicated being is a god, a devil, a saint, or a tree sprite, and it doesn’t matter whether the believer locates this being inside or outside the universe. From a secular point of view, the essential feature of magic is the appeal to a supra-physical personal agent to contravene the physical laws affecting some outcome in the material universe. It is the belief that the meaning of an act can have causal significance beyond the physical characteristics of the act, the belief that saying the name of the right god or spirit makes a difference beyond the mere differences in the waveforms of the sound of the names. From this secular point of view, Christians believe in a magical world. You are of course welcome to define yourself out of this conclusion, but the essential point remains.

Typos….should be “just as biologists define “bug” as an insect belonging to the order Hemiptera”

Lou,

The examination of a term must begin with its history and this is what Jon is doing – historically the term ‘magic’ and associated activities has been understood as Jon has pointed out, i.e. superstition, trickery, or a belief that is traced back to pagan practices; ALL of the evidence shows it is clearly contrary to the Christian faith.

Your comments would make sense only if you re-defined the term to mean generally a belief in things other than the physical. If this is so, many things can be argued to appear magical.

Your argument imo is more along the lines, (1) belief in God (or gods) must by definition be termed magical (this is an incorrect definition), or (2) any non-physical aspect of reality must be termed magical.

The (2) outlook is so general that it is vacuous; otherwise if you are an atheist, all other outlooks must be termed magical; if you believe in God all such belief is magical. In this case, it is ones belief that is discussed, and a term such as magical is a useless addition, or used rhetorically to denigrate by making it appear unscientific (and you have habitually displayed this outlook).

Christianity has clearly and consistently rejected the occult, the superstitious and the demonic – this is a fact that is supported by an enormous amount of historical data – it is odd, to say the least, that you ignore such facts.

“Christianity has clearly and consistently rejected the occult, the superstitious and the demonic”

GD, from a secular perspective, there is no difference between a superstition and a belief that if you can pray to an immaterial being, this being might intervene in the physical universe to satisfy your requests. I’m not arguing now about whether this being exists or not, I am just suggesting that the distinction you are making is not significant if that being does not exist.

Lou,

I fail to see the point you are making – it is axiomatic that if someone does not believe God exists (or gods for that matter), then that person would not believe in anything associated with God or gods. The discussion is on using the term magic within the Christian faith. If one professes the Christian faith, one also rejects all things associated with (the normal use of the term) magic. That is a clear and obvious distinction – you may not believe it is, but your position is an absence of belief in all but the material – so how can you construct an argument that the Christian faith is equated with the magical? Your position is just too irrational (ironic for one who values the scientific and the rational, wouldn’t you say).

GD, as I mentioned in my first comment above, I understand that Christians make this distinction, and they have every right to do so.

However, it should be obvious that if there is no god, then your belief in things like intercessionary prayer would be false, and would therefore not be different from the beliefs you condemn as superstitions. So if there is no god, there would be no real difference between a belief in intercessionary prayer and a belief in magic.

Anyway this is a silly thing to be arguing about. I’ll stop here.

Lou

The problem with this is that it’s factually and linguistically completely wrong. It’s just as wrong as saying that an egg is a radio. I presented a secular point of view by sourcing mainly secular historical texts for my piece… unless we’re to take “secular point of view” as meaning your own idisosyncratic use of language (as GD has pointed out).

The fact is that magic does not depend on belief in personal agents – that was the specific distinction in Renaissance times between “natural magic” and “ritual magic”. And even ritual magic was seeking toharness spiritual beings’ powers, not contravene anything (except, perhaps, God’s prohibition). Magic is about the powers of nature, not their contravention, and always was. Even in Babylonian times the gods were subject to the laws of fate that governed their magic.

At the time when magic was a real issue, there was not even a concept of physical laws to contravene, Aristotelian essential natures being the prevalent concept in science. And it’s pretty doubtful that anyone thought the universe was material in those days, because material without substantial form (an immaterial concept) didn’t even exist.

If words can mean anything, they mean nothing, despite Tweedle-dum’s claim that a word means precisely what he chooses it to mean. If you had followed the link I put in to Porta’s “Natural Magic”, which as I read it appears to be one of the first serious textbooks of natural science – no doubt why it was mined so comprehensively by the father of science, Francis Bacon – you’d have seen that he makes very careful definitions, distinctions and historical discussion of magic before cutting to the details. It becomes very easy to see how those ideas became refined and adjusted during the following century, eventually leading to dropping the whole concept of magic. Porta’s mindset has great explanatory power for understanding a major component of early-modern science. Your pseudo-definition of magic does not – it simply makes science appear “magically” ex nihilo from the eighteenth century rationalists.

But if you insist on ignoring the history of ideas and squeezing everything through the culturally restricted sieve of western 21st century popular secularism, then it’s a highway to ignorance, I’m afraid, of exactly the same nature as the highway the Fundamentalists one sometimes meets at BioLogos are on.

Though there wasn’t room to quote more than a couple of paragraphs, Copenhaver’s survey of exactly how the science of (specifically Boyle) differed from that of Agrippa – which was principally more about describing occult forces visually rather than as sensations – is enlightening and forces one actually to think about the modern presuppositions one takes for granted.

The reading for this post taught me a fair bit of historical philosophy of science, as well as some of the actual concepts behind the term “magic”, about which I knew very little before. You can redefine magic, if you wish, to mean “any supra-natural personal being contravening physical laws”, just like some wiseacres have chosen to redefine the 17th century word “pixie”, a mythical, childlike creature inhabiting the wilder parts of my own locality (west England), to mean the eternal Creator of all things. But if you do it will simply sideline you from any serious discussion of the issues, because it will show a lack of commitment to any real intellectual effort.

Like I said several times, I recognize that Christians want to use the term “magic” in this way, and have done so for a long time. But there is a wider world out there, and that wider world also finds the term “magic” to be useful. GD says that something is magic if it invokes superstition. In a wider world in which Christian beliefs are thought to also be superstitions, GD’s own definition of “magic” applies to the supplications made to the Christian god, and their supposed effects.

My last word on this Lou – is the Oxford English Dictionary a Christian?

magic, a. & n. (Of) the pretended art of influencing course of events by occult control of nature or of spirits, witchcraft; black, white, natural, m. (involving invocations of devils, angels, no personal spirit [respectively]).

Its seems that although the Roman Pliny persecuted Christians in the first century, they had developed a theology of magic already, which unaccountably he had adopted.

If GD’s off-the-cuff “superstition” constitutes a formal definition, I take it that you also apply the word magic to all “trickery” too. There’s sure a big wide world out there, full of Tweedledums abusing language. But I guess I already knew that from visiting Gnu websites.

Jon, I was intent on making one point clear, and that is the attitude and outlook of the Church to magic and superstition. I have tried to be charitable to Lou as he obsesses with Christian practices such as prayer, but I must confess that I view his opinion shallow and thus do not spend time making a considered response. Nonetheless, it may be appropriate to consider a few comments which I consider representative of the atheist/theist debate, and I offer this in an attempt to add a serious point to the otherwise odd exchange with Lou:

“The Kantian critique of metaphysics ends up appealing to a fundamental alienation grounded in an austere mechanical universe that cannot give rise to freedom. Kant leaves human beings in what Hegel and Marx might have called the position of being both freely subject to the moral law and determined by an objective world of nature that has been stripped of any value and which stands over against human beings as a world of alienation. Individual freedom in these days reduced to an abstraction in the face of an indifferent world of objects that are available to one as commodities. Reason functions in this atheistic / theistic debate in a very limited, even reductionist way as it becomes the final arbiter of all truth forced into propositional form and thus sundered from everyday life.

I cannot help but add (with a smile) a comment by Zizek (a rabid atheist imo) who lamented the fact that he could not find Christian atheists. He seems to like some things about Christianity, if only they did not believe in God and other things Lou is obsessed with.

I think this is an amusing point to end this discussion.

Jon, in the secular view, that dictionary definition applies to Christians supplicating their imaginary spirit to influence nature.

Lou, even though this is off-topic, perhaps your time would be better spent reading articles such as this op-ed in the Wall Street Journal titled the “Global Religion Crisis” that references a State department report on the subject:

http://online.wsj.com/articles/the-global-religion-crisis-1406824905

Hmm, I looked at the intro (the rest requires login or subscription). I’ve picked up bits and pieces from elsewhere. The irony of this problem is that almost all religious repression is done by other religious people who are sure they are right. China and North Korea are the exceptions.

Eddie mentioned in another thread that he would rather live next to a devout Christian who believed that God ordered the genocide of Canaanites, instead of a secular humanist. The problem with such religious people is that they often find ways of excusing atrocities when they think their god commands them (we have even seen such excuse-making creep into this blog’s comment sections when discussing Yahweh’s atrocities). That attitude among the fervently religious facilitates violent repression against minority religious beliefs worldwide, as far as I can tell.

Yes, given the large portion of the world that is at least nominally religious, it would be surprising if religious people didn’t also make up the majority of the miscreants.

I am glad that you have been bequeathed …from some mysterious place or another… the standards that enable you to recognize the atrocious nature of some actions and the hypocrisy of religious people who do them. That is very hopeful. In places like North Korea or the former communist states there was no hypocrisy, just a playing out of how the dedicated secular mind also fails to be immune to violence as it invokes ideologies of its own. At least Muslims or Christians can be called to account for their atrocities on the basis of things taught in the Bible or the Quran. For every atrocity justified by some holy writ, there were others willing to correct the error from the same Witness the widespread Christian basis of abolition in the face of the shallow justifications that had been invoked for slavery. Or the religious foundation for Martin Luther King Jr. as he followed Jesus’ teachings to bring down that same kind evil that still lingered in so many southern white churches. The Bible amazingly fuels the correctives against those who abuse and appropriate it to their own purposes.

But what do the secularists have to offer in its place?

Sorry about that link … I notice now too that it lands you on the outside of a subscription wall, whereas when I linked to it from a Google news search, the whole article was available. Just Google: global religion crisis wsj

and the top link should allow you to see the the full article.

Secularists have the same golden rule as you guys profess to have. It makes sense to try to construct the kind of society we would like to live in. Enlightened self-interest and the interests of our descendants. What we don’t have is the subsidiary normative junk that many religions carry with them as leftovers of their past (and sometimes present) role as tribal identity badges.

And it works. Many secular societies are healthier than the more religious societies. I can’t assign causality here, but these societies prove that we can function perfectly well (in fact, better) without religion. Many of the most secular European countries are also the highest-ranking countries in terms of commonly-used indicators of health and happiness, and have the lowest crime rates.

Religious people like to point out that these secular countries have a Judeo-Christian heritage. Fair enough. But so do many terrible, sick countries.

“..given the large portion of the world that is at least nominally religious, it would be surprising if religious people didn’t also make up the majority of the miscreants.”

Well, one could also argue that religious people should be the ones who should most value religious freedom. Looks like it often doesn’t work out that way. In the US, Christians are quite xenophobic with respect to other religions.

“At least Muslims or Christians can be called to account for their atrocities on the basis of things taught in the Bible or the Quran.”

That’s not what happens. The Bible and especially the Quran can also be interpreted as justifying such atrocities, when one wants to justify them.

I had written: “At least Muslims or Christians can be called to account for their atrocities on the basis of things taught in the Bible or the Quran.”

Lou responded:

“That’s not what happens. The Bible and especially the Quran can also be interpreted as justifying such atrocities, when one wants to justify them.”

Your response is demonstrably false in the examples I gave (abolitionism in Europe and Americas and later civil rights movement in the U.S.) And more examples can be given.

For examples of the kind of tolerance that we might historically expect in the name of secularism we find things like … the French revolution. A more positive example of a positive non-sectarian organization might be doctors-without-borders, though many Christians support that; and I doubt such organizations fly the flag of anti-religion given how distracting and detrimental that would be to their own mission.

Which nations do you have in mind for these happy secular nations? In the allegedly “post-Christian” Europe nearly every nation (yes, including those in Scandinavia) has a vast majority of self-identifying Christian folks as of last survey in 2010. The couple of glaring exceptions I recall were the Czech Republic or Estonia — “Glaring” because of their anomalous contrast with their highly Catholic or Lutheran neighbors.

“Your response is demonstrably false in the examples I gave (abolitionism in Europe and Americas and later civil rights movement in the U.S.)”

Actually your counter-response is demonstrably false. I wrote that the Bible and especially the Quran were complex enough that they could be used to support as well as castigate many atrocities. The Bible was in fact used that way in the southern US to justify slavery. Whether their interpretation was correct or not is beside my point, which was that the Bible is ambiguous enough to easily countenance many kinds of atrocities.

As further evidence of the Bible’s ambiguity on this subject, consider that slavery was just fine in the eyes of large numbers of Christians for at least 1500 of its 2000 years. Many well-known church fathers explicitly accepted slavery. Wikipedia has some quotes from them:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_views_on_slavery

On your second point, I was thinking especially of Denmark and Sweden. Regarding Denmark, another survey says “According to the SKYE most recent Eurobarometer Poll 2010,[2] 28% of Danish citizens responded that “they believe there is a God”” If that is in the ballpark, and if your poll is also correct, I guess Danes have a different definition of Christianity than you do.

This NY Times article describes the nature of religious belief in Denmark:

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/28/us/28beliefs.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

To be exact, Eddie wrote:

“It [the Old Testament] is certainly a much more moral book, with all its faults, than the books of the influential modern teachers — Freud, Skinner, Heidegger, Derrida, Foucault, Camus, Peter Singer, Will Provine, etc. — all written by narcissistic egomaniacs, and all of which offer civilization nothing but nihilism and despair. I would rather have, as a neighbor and friend and fellow citizen, a man who truly believed that God delivered the Ten Commandments and followed them with all his heart and soul, even if that man also believed that God ordered the slaughter of the Canaanites, than any leading modern secular humanist intellectual.”

The words “and followed them [the Commandments] with all his heart and soul” were crucial to my statement. A man who follows the Commandments with all his heart and soul is very likely to be a good and just man (I’m of course speaking generically here), and therefore is very likely to find troubling the passages about God’s ordering the slaughter of the Canaanites — but might still believe in the truth of such passages, because he might feel obliged to accept all that is in the Bible, even where he cannot yet see how it fits in with God’s wisdom or goodness or justice.

The secular humanist throws out the good with the morally troublesome; the troubled believer makes sure that he hangs on to the good (even if that means giving nominal assent to the passages that are troublesome). In practice, the believer of the sort I’m describing would himself never dream of slaughtering populations, enslaving women, etc., or of ordering anyone else to do so. In practice, i.e., in the real life of Jews and Christians today, those troublesome passages are not operative as guides to behavior. There may be other religions today (or extreme subsets of those religions) in which analogous thoughts about God are operative, but if so, Judaism and Christianity are not among them.

“The secular humanist throws out the good with the morally troublesome; …”

That isn’t completely fair, Eddie. Could we say that secular humanists borrow the concept of “good”, and then later look at us with such naively innocent faces asking “what? –that was ours all along!”

I think we are talking at cross-purposes, Merv.

All that I meant was: the secular humanist says that the parts of the Bible that have God slaughtering people aren’t true, and also that the parts of the Bible that declare God’s existence and goodness and justice and revelation (in the Ten Commandments or in the person and life of Jesus) aren’t true. The humanist throws out the baby with the bathwater. Because religious books and traditions contain some elements that aren’t in line with modern moral standards or modern scientific thinking, the books and traditions are regarded as unreliable and something we would be better off without.

My approach is different. I concede that certain aspects of the Bible and of Christian tradition are troublesome — and not just for secular humanists but even for Christians; but I see texts and traditions not as polished diamonds without a flaw on even a single facet, but as pretty high-quality gem stones whose seeming defects don’t prevent them from being beautiful and precious. I’m not going to throw away my flawed sapphire or emerald until someone gives me that perfect diamond; and secular humanism is far from a perfect diamond.

My approach is also different, Eddie. I do not argue that just because a god is sometimes nasty, he must not exist. As you’ve mentioned before, a god might really be nasty.

I used these passages mainly to argue that there is a contradiction between today’s Christian concept of god and the god portrayed in some parts of the Bible. I do not conclude from this that the Christian god does not exist, but rather that the Bible cannot have been directly and carefully inspired by the Christian god, even if the Christian god existed.

I don’t really find atrocity arguments to be compelling arguments against the existence of god. The strongest argument against the existence of a historic, personal, theistic Christian god is the absence of evidence for this god in places where one would expect to find such evidence if he existed.

I understand all of that, Lou, but what I’m saying here is that your overall position is that the Bible doesn’t have much truth in it, that Christianity doesn’t have much truth in it, and that if Christianity ceased to exist, the world wouldn’t lose very much, and anything good that it did lose could easily be recovered by a proper secular humanism.

I think that the good things in secular humanism are largely (not entirely, but largely) parasitic on Christianity, not in the narrow sense that they depend on a doctrine of Fall or Virgin Birth or the inerrancy of the Bible, but in a deeper metaphysical sense — many of the things that seem just obviously good to a secular humanist did not seem so to most pre-Christian cultures.

Regarding your example of Confucius, it is an old story (and one told by Lewis as well) that there is some overlap between Christianity and other religious traditions. Nonetheless, even Lewis at points exaggerates the overlap. He is right to grant the common elements, but the differences are striking. Confucius, for example, sometimes says things that sound Christian, but of course much depends on translation (and some translators, good liberals bent on showing all religions are the same, cheat a little), and even where the odd teaching is the same, many other teachings are different. Confucius’s “goodness” is not all that much like Christian goodness, when his whole teaching is examined. It is the goodness or virtue appropriate for a snobbish, delicate, and rather self-satisfied class of urban gentlemen-bureaucrats, not for Francis of Assisi or Mother Theresa.

Aristotle’s understanding of goodness has analogous problems. Clearly it has some overlap with Biblical ideas, but on the other hand, the highest type of human for Aristotle, the magnanimous man, is not animated by anything like Christian sentiment, but by something that Christian teachers preached against for centuries as pride.

My point is that we all think and feel very differently because Christianity has existed and has redefined, for a good part of the human race, what it means to be a human being, what virtue is, what ethical behavior is, what justice is, and so on. Secular humanists now claim to be able to found all these notions on purely secular principles, so that we can have the ethical and social results without any of the Christian metaphysics or Christian sentiments, but the claim is highly dubious.

I think that secular humanists — at least the most influential secular humanists in the world of popular culture — do not do justice to the historicity of human thought and feeling. We are not abstract intelligences sitting down in a committee to decide (based on reasonable neutral principles that would be acceptable to all men everywhere) what the principles of humanity and virtue are. We already, whether Christian or atheist, bring a colossal amount of historical baggage with us in the very way we frame the questions, go about seeking answers, adjudicating between various suggestions, etc.

Even the brightest and most self-critical are shaped by inclinations whose origins are very hard to bring clearly to consciousness, but are in many cases Christian in origin. I find your own expressions of ethical horror at much that Christians have done and some parts of the Bible to be themselves motivated by Christian sensibilities, even though you have dropped all Christian doctrines.

Of course, Nietzsche explained long ago that there would be a period during which society would continue with Christian ethics even though Christian metaphysics was consciously opposed. But he knew that this interim period had to be finite, and hence that ultimately a new morality based on non-Christian metaphysics would arise. He did not the think the new morality would be very close to Christian morality. Enter the superman.

You are a very old-fashioned secular humanist in that you are still charmingly Christian in your moral evaluations. I think the future of secular humanism is seen more in people like Peter Singer, and some of these people who are writing about transhumanism. Once you drop Christian metaphysics, there is no compelling reason why the premises of equality and fraternity have to restrain the liberty of the talented and inspired few who have acquired means to make their social vision a reality. Lewis talks about this in The Abolition of Man, and Orwell deals with it in 1984 in his own way.

Again I mean Christian metaphysics here in a fairly broad way. I don’t mean that decent ethics depend on every member of society understanding and affirming the the abstruse arguments concerning the Three Persons of the Trinity. I mean things such as the assumption about the inherent and equal dignity of all men, even the lowliest, premised on the doctrine that all men are created in the image of God. I think that such teachings are in the blood and bones of secular humanists (of the older type) and Christians alike. I think they will not be in the blood and bones of the secular humanists of the future.

I am not willing to count on the continuation, in the secular humanists of 50 years from now, of your Christian-like form of secular humanism. Therefore I oppose secular humanism, not in all of its statements or values, but for its overall metaphysical grounding (or lack thereof). Without the implicit Christian-Platonic metaphysics that spawned it, it is a house built on sand.

Merv, surely you don’t believe that secular people could not have been good if they had not heard about the Christian god and his ten commandments???? As one counterexample, Confucius arrived at a version of the golden rule without any input from Christianity.

I’m going on a field trip for a week so won’t be able to respond for a long while…..Hasta luego

Thanks for the link to the NYT article (appears to be based on a 2008 study) — that helped give more detail to what’s going on here. Just to contrast it … the Pew Forum study (2010) that I was referencing has Denmark self-identifying as 85% Christian and 12% Unaffiliated and Sweden as 67% Christian and 27% Unaffiliated. These are just what people are calling themselves. If one tries to delve into questions like … do they really mean it … or do they actually embrace the right set of beliefs to qualify, then this opens all sorts of doors that atheists have sometimes objected to as a “no true-Scotsman” fallacy (often as a desperate gambit to convince themselves, for example, that Hitler was really a Christian because he called himself one at some point). But I am more than happy to acquiesce, having recognized that such objections are deeply nonsensical, and that it is a thoroughly Christian idea to recognize a tree by its fruit rather than its words.

So in that new and improved vein of thought … here was a fairly revealing paragraph from the article you referenced regarding Scandinavians of Sweden or Denmark.

“Though they denied most of the traditional teachings of Christianity, they called themselves Christians, and most were content to remain in the Danish National Church or the Church of Sweden, the traditional national branches of Lutheranism. ”

The article describes how the impact of church or Christian teachings is very minimal or usually limited to holidays or ceremonies. I found it interesting that they weren’t at all found to be hostile to Christianity or religions generally … just indifferent to them in their daily activities. But when pressed on it, apparently a lot of them still balk at the label “atheist”. Hence the results of the other study that would lump apparently nominal Christians in as Christians. In fact they even thought of Christianity as teaching “some nice things”. Apparently they aren’t as perceptive as you are, Lou, being unable to see that Christianity really teaches “nice things” and atrocity equally according to whatever cultural preferences dictate.

And on that subject, if you’re going to play the “but some have misused it that way” game … then you must throw all of science out as a dangerous enterprise since it too has been enlisted in the service of various evils. But once we see through that ploy and return to reason, we see that there is no contest here. The Christian abolitionists won. Full stop. There is no debate on whether Christianity can legitimately sanction slavery today … it can’t, except in the imaginations of a few religiously devout atheists. Another piece of history that I think Jon has referred to before is that slavery of ancient times was really rampant in Greek / Roman / and barbarian cultures prior to the middle ages, and then with the growing influence of the church up and into the middle ages, slavery (because of religious sanction) became (nearly?) nonexistent until the discovery / exploitation of the new world and the industrial revolution introduced a powerful economic incentive institutionalize it again. Then it unfortunately exploded into the western scene again. Maybe Jon can help me remember where I read this or if there were any statistics on it.

MLK Jr. enlisted his Bible against the injustices of the southern white sheriffs and he won. Whatever leg the racists thought they had to stand on (to the extent that any of them even bothered to try finding scriptural sanction) … they were blown away. As any open-minded individual can see today they had no comparable moral ground on which to stand. There is no … well the Bible can be interpreted either this way or that way; on issues such as this, there was only one winner. The losers were exposed as having had other motivations to do what they did and they attempted (unsuccessfully, it turns out) to bend passages around to justify what they had already embraced on other grounds.

Perhaps we can continue this more later after you get back. Much thanks to Jon for his patience in allowing this space for us to go crashing off pell-mell through the forest away from his topic.

There is one other distinction that also many fail to make … that while all slavery is injustice, yet not all slavery is the same. The latter form of slavery that developed in the west was a particularly pernicious form of “chattel” slavery (based on race) in which people with certain skin color had no chance of ever being anything but property once they were kidnapped into such a cruel system. Whereas the older slavery (perhaps distinguished as indentured servanthood) was more an economic slavery (still oftentimes cruel, I’m sure, but not based on skin color). If one got themselves into dire financial straights they might need to sell themselves and/or their families. But at least they had a possibility of working themselves to freedom again. While we rightly oppose any form of slavery we are ignorant if we imagine that no such slavery exists today –even of the systemically cruelest kind. Lord, help us to refrain from squabbling over who is more at fault when we need to be working together to end it!

Merv

Good points – there’s a comment on the Dangerous Idea blog, which has a current thread on slavery, to the effect that one evil of slavery is that society loses the creativity and inventiveness of those enslaved. That’s completely true for the chattel-slavery of modern times, of course – but in Roman Society slavery was such an entrenched part of society that it could be more like a caste-mark than a job-description. Slaves were in positions of responsibility and could be teachers, accountants, physicans etc.

Furthermore, slavery in the ancient world was not so much a feature in society, like abortion or sex-trafficking: it was society, at the kind of level capitalism is now. The task of abolishing slavery was exactly the same task as rebuilding the society from the ground up – or from Year Zero, if you understand the allusion.

The comments made about the New Testament not condemning slavery need to be seen in this light. It’s also unjust that nowadays company executives should be paid hundreds of times the average wage whilst their employees need state benefits to survive. Preachers (and journalists, politicians etc) will sometimes speak out against it and suggest things to reduce the disparity. But it’s certainly not the constant refrain of all people with a moral conscience that capitalism must be abolished (I’ve seldom heard prominent atheists mention wage inequality, for example), simply because such a radical revolution would likely cause total chaos rather than an egalitarian utopia.

Similarly it is an injustice that people should be unable to support themselves through work, but unemployment happens. Both here and in the US our answer, in a highly developed bureaucracy, is to pay the unemployed enough to survive for a few months, and then leave them to suffer if there are no jobs. The redundant rich, however, get million-dollar payouts and always seem to find work at salaries that would support a city-full of unemployed workers. Sometimes their pay is a reward for reducing the workforce.

In the OT world, selling yourself gave you permanent work, with (in the Hebrew system) release at the Jubilee.