Since we’ve been talking about worldviews, let me refresh a theme I’ve covered a little before, and that is how difficult it is for us moderns – whether Christians or not – to escape from our materialist worldview at its broadest. By this I don’t mean the idea that the material is all that exists (snare though that is), but the fact that, for all of us civilized folks, material explanations for things remain the default “reality.”

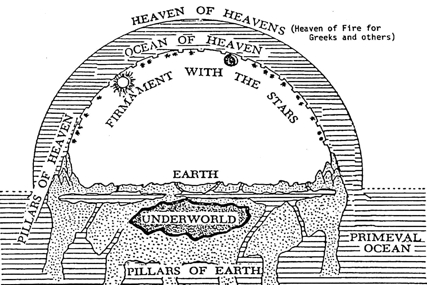

Picking up the theme from the 2012 blog linked above, the idea is commonly put about that Genesis 1 is discussing spiritual themes in the context of “ancient science”. So whatever the truths (or otherwise) about God and creation within it, the ancient Israelites “really” thought about the scientific nature of the world as having pillars, a solid raqia firmament and so on thus:

But whilst there’s clearly a connection with the physical world (for example water comes from the sky, disappears into the ground and sea, so most rationally must surround us too), diagrams like the above are actually modern materialist projections on descriptions that in all probability are not intended as physical at all, because “pre-scientific” doesn’t mean “false views of physical reality” but “non physical views of reality.”

But whilst there’s clearly a connection with the physical world (for example water comes from the sky, disappears into the ground and sea, so most rationally must surround us too), diagrams like the above are actually modern materialist projections on descriptions that in all probability are not intended as physical at all, because “pre-scientific” doesn’t mean “false views of physical reality” but “non physical views of reality.”

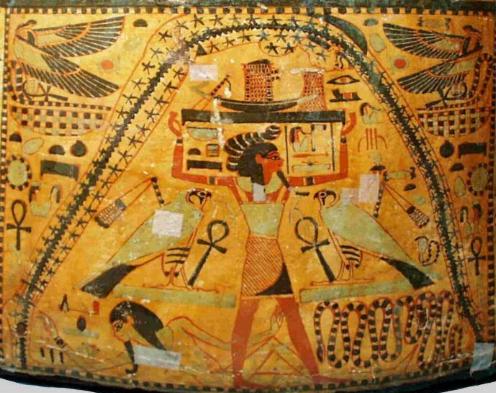

This is the substance of Owen Barfield’s book (which pngarrison has promised to review for us at some stage – watch this space). We can also illustrate it by the highly developed, but non-scientific, Egyptian cosmology. You may be familiar with variants of this graphic:

The sky goddess Nut is supported by her brother the air god Shu, whilst the earth (Geb), exhausted from coitus with her, reclines beneath. Various other things are going on to keep the cosmos going, like Ra, the sun-god in his boat, and so on. G K Beale in his work The Temple and the Church’s Mission points out the rather obvious fact that the Egyptians must have been well aware that the earth and sky don’t look like that at all – not a single god is to be seen. But to call the representation symbolic would be false – they truly believed these elements were living deities.

The sky goddess Nut is supported by her brother the air god Shu, whilst the earth (Geb), exhausted from coitus with her, reclines beneath. Various other things are going on to keep the cosmos going, like Ra, the sun-god in his boat, and so on. G K Beale in his work The Temple and the Church’s Mission points out the rather obvious fact that the Egyptians must have been well aware that the earth and sky don’t look like that at all – not a single god is to be seen. But to call the representation symbolic would be false – they truly believed these elements were living deities.

Neither were the gods invisibly indwelling or empowering the physical reality. Rather, the reality wasn‘t physical – or maybe, they saw the physical world as merely symbolic of the reality. In other words, the gods weren’t invented to explain the fundamental physical reality (as Carl Sagan imagined), but the world of the senses explained the spiritual reality. Confusion over that explains why ancient mythologies – be they Greek or Australian Aboriginal – just don’t seem to make sense to us. Mapping their stories and entities on to the physical world often just doesn’t work. And it’s because to them it’s the physical world that maps on to the organic or spiritual reality.

Returning to that first generic “ANE/Israelite cosmology” graphic, a similar worldview – though dramatically transformed by monotheism in the latter instance – is the case. God is no longer the cosmos itself, for he made it and everything in it. But it is the temple he has erected for his worship, and since it is a temple, that’s the physical concept through which it is expressed, rather than as the Egyptian biodrama.

Incidentally, other ANE cultures shared temple imagery together with their paganism, which is why you won’t find the illustration above on any Mesopotamian tablets – strange as it may seem it’s as modern a representation as Creationist accounts of Genesis are… though we should not excuse either the thoroughly modern TE accounts in which Genesis obliquely is said to describe evolution. It doesn’t, not only because modern science would have made no sense to readers at the time, but because the whole physical subject-matter of science made no sense at the time.

So, a temple has pillars, a roof , divisions into more or less holy rooms, sacred lights and so on. God’s cosmos therefore has them too. Israel’s temple even had a large “sea” in the courtyard. Beale points to how many cosmic themes are represented in the biblical descriptions of the Temple, but at the same time the nature of the cosmos is represented in terms of the Temple. They’re both the same type of thing, and the imagery serves both. Is the Temple’s sea a representation of the cosmic waters, or vice versa?

To ask how the writer of Genesis “really” thought of the world, meaning whether it was flat, whether the stars were painted on a solid firmament or above it, etc, is a question that would probably have puzzled him: he was describing the world as it essentially is – that is, God’s Temple – and he kept his mind off the phsyical structure more because it was irrelevant than unknown. Talk of “ancient science” is as meaningless as wondering about Jerry Coyne’s view of the spiritual structure of the universe.

If it sounds as if the ancient peoples ought to have been more inquisitive, consider that children cope very well in the world before they have any idea of its shape, structure or place in the Universe. And I doubt that any one of us has any clear picture of the shape of the Universe according to modern science – if we do, it’s probably wrong.

Let me add one more illustration. I’ve heard literalist (ie unconsciously materialist) speakers expounding on the New Jerusalem in Revelation 21-22. The cubic city, they say, would fit just inside the moon so there will be plenty of room. Much discussion on sourcing of huge pearls for the doors (huge oysters in the cosmic waters?). And so on. All this misses the fact that these passages are an apocalypic description. More properly, Revelation is a blend of five approaches: Scriptural, Historic, Apocalyptic, Ritual and Prophetic (remember that and your interpretation of it will be SHARP). But if you asked St John what he really imagined the new creation to be like, behind the symbolism – that is, about the material science of the new order – he’d have said, “I just gave you the reality – why do you ask about the trivial?”

The river that flows from the throne of God in Revelation 22 is identical to the river in Ezekiel and various other prophecies of the OT. It relates too to the river flowing out of Eden, and also to the waters fundamental to the Genesis 1 account. I’d suggest that it’s no more a representation of “scientific thought” in the first than it is in the last. “Pre-scientific”, then, doesn’t so much mean giving different explanations for the world (by implication inferior to ours), as it means describing a different world altogether. A world we’ve all but lost sight of beneath a pile of rocks, chemicals and space-time.

As C S Lewis wrote in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader:

“I am a star at rest, my daughter,” answered Ramandu. “When I set for the last time, decrepit and old beyond all that you can reckon, I was carried to this island. I am not so old now as I was then. Every morning a bird brings me a fire-berry from the valleys of the Sun, and each fire-berry takes away a little of my age. And when I have become as young as a child that was born yesterday, then I shall take my rising once again (for we are at earth’s eastern rim) and once more tread the great dance.”

“In our world,” said Eustace, “a star is a huge ball of flaming gas.”

“Even in your world, my son, that is not what a star is, but only what it is made of.”

I had to laugh over the Coyne comparison! What a great analogy.

Walton’s essays on this have always made a lot of sense to me as well — the ancient writer(s) being concerned with *functional* realities as opposed to material realities. But your point is well taken that just thinking of it as symbolic doesn’t capture it either as they would have thought these things quite real in any and every sense of that word. We just have additional (or maybe re-prioritized rather) uses for the word “real” that they may not have shared.

The Dawn Treader quote is also excellent. I’ve remembered and used that one myself on some occasions. Another comparison (also from Lewis) is that the materialist may argue that a poem is nothing more than ink marks on a paper medium. But an understanding reader rightly apprehends quite another (and much more significant) reality as to what those marks actually are.

-Merv

Merv, your poem metaphor is particularly apt to my theme here, tying in as it does to ideas on information/formal causation etc. Thanks.

It’s probably pretty reasonable to say that our default, scientific, view of the universe is exactly the equivalent of the cartoon-materialist’s description of the poem. Whereas the Bible’s description is of the poem (as were other ancient views, only they were different, less truthful, poems).

It’s not at all fanciful if you consider that the scientific project specifically depended on sidelining final causation (purpose) and formal causation (information), in favour of efficient and material causation. The ancients could be said to have treated the material world as we treat the physical media of print: as a mere vehicle for what is really important.

One is very glad there are paper technologists, printers, bookbinders etc, but they shouldn’t be the arbiters of literature.

Hi Jon,

Thanks so much for this piece. I know the literature you cite and have come to similar conclusions, but have never thought it through so clearly and insightfully. Very helpful indeed.

And thank you, Arthur. Echoing Merv’s comment, John H Walton’s work was the catalyst for my thinking on this (and he proved a very approachable chap), together with some serendipitous discoveries about worldviews and genre in literature.

Another side of the coin was included in an essay I did in my early post-retirement and pre-blog explorations of this stuff.