Evolution was first presented as a theory of biology, but soon become the definitive way of thinking about every conceivable process involving time. In a real sense, it’s our culture’s “theory (or metatheory) of everything”, so that it’s not unfair to label the predominant worldview of the West, and not just of some atheist subset of positivists, as “Evolutionism”. Let me demonstrate this from both academic and popular sources, mixed indiscriminately.

If we consider the scientific, it’s not only life that has evolved but the atmosphere, the oceans and the earth itself. But astronomically evolution is considered the key also to the solar system, stars, galaxies, and the universe. Even multiverses evolve, in one way in Lee Smolin’s theory, and in quite another in the many-worlds interpretation of quantum theory , where the evolution of the wave function leads to the evolution of multiple worlds. Examples, can be multiplied, it seems, in proportion to the number of subjects science covers.

If we consider the scientific, it’s not only life that has evolved but the atmosphere, the oceans and the earth itself. But astronomically evolution is considered the key also to the solar system, stars, galaxies, and the universe. Even multiverses evolve, in one way in Lee Smolin’s theory, and in quite another in the many-worlds interpretation of quantum theory , where the evolution of the wave function leads to the evolution of multiple worlds. Examples, can be multiplied, it seems, in proportion to the number of subjects science covers.

In the human world, though, it’s the same. Society and culture, of course, evolve, and so do the languages they speak. But lest we think only in terms of long-term quasi-biological concepts of language, then even designed and commercial languages, such as computer programs, fit the evolutionary mould. The same is true of other human constructs like money – a whole series of Reith lectures was given over to “evolutionary economics” a year or two ago . Evolution-talk is so pervasive that it doesn’t seem strange even to talk about the evolution of a marriage.

Now, somewhere lurking behind this is, without doubt, a metaphysical agenda of weakening the ideas of choice and design, making even hard-won improvements to the design of aeroplanes, cars or vacuum cleaners appear as some kind of natural and ultimately materialistic law rather than the intentional work of people or the Creator. But whatever the reason, evolution underpins our thought-system as much as, or more than, the Great Chain of Being did that of an earlier age.

I was set off on this train of thought by a chance remark by Roger Sawtelle in a reply to GD on BioLogos (odd – I got a disciplinary e-mail for posting a reply to a commenter instead of to the author the last time I posted on there. The rules must be evolving in real time, though theistically). Roger happened to mention in passing that “science evolves”, which simple observation triggered in me all the thoughts above, but also got me to wondering if science really has evolved, in the sense of seeing itself in the way that modern, rather than nineteenth century, evolutionary theory would picture it. For evolution itself has evolved greatly in the last 150 years.

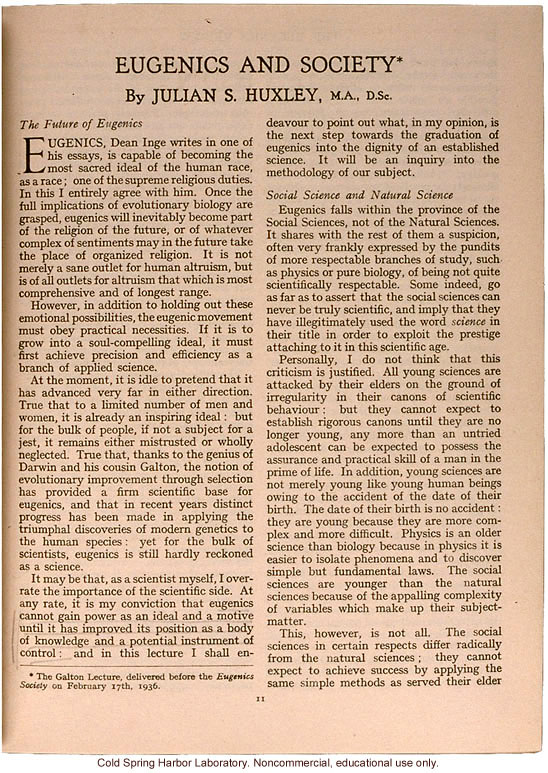

The Spencerian philosophical cast which capitalised upon and popularised Darwin’s theory, leading to the “evolutionistic” worldview outlined above, was that life, originally primitive, simple and crude, would be progressively honed by variation and natural selection, so that without any inbuilt teleology it would come, at last, to perfection. Civilized Western man, of course, was the current culmination of that age-old law, but it was fully anticipated that nothing could turn the tide of progress back in life’s course, any more than it was conceivable that the white races might, contra Darwin in Descent of Man, be replaced by primitive Aboriginals rather than the reverse. Evolution was a law of history, as Marxism overtly claimed in politics – an important example I seem to have missed out in my initial exposition.

Now, the science of the time was, conceptually, in tune with that philosophy. Go back in time, and human knowledge becomes more crude, primitive and erroneous. Go forward in time and science will be seen to become purer, stronger and more perfect. That is the law of progress, and it applies to science in a linear manner. Science is always self-correcting, always developing, and ultimately complete. Now it sees through a glass darkly, but then it will see face to face.

The trouble is that, as evolutionary theory has developed, it has become clear that biology has no truck with any such philosophical principle of inevitable progress. I’ve touched on that in a number of posts here, but it’s hardly controversial. Neo-catastrophism has replaced the near-religious adherence to uniformitarian principles – the dinosaurs were replaced by mammals not because the latter were superior, but because they just happened to be better at surviving asteroid strikes through being smaller and less successful.

Yet recent research has shown that even whilst the dinosaurs lived, mammals were as diverse as they are now, rather than being (as previously believed) basic forms hiding in burrows out of the way of reptiles. In fact, it has become abundantly clear that though there have, in retrospect, been historical trends in life’s history, ancient species were neither simpler nor less adapted than those living today. Dinosaurs were warm-blooded and feathered. Trilobite eyes were optically perfect. LUCA was at least as complex as a modern cell. DNA was a near-optimal semiotic code back in the Precambrian.

Even if we ignore the currently popular and profoundly un-progressive doctrine of neutral evolution, adaptation is now realised to be nothing to do with progress towards some ideal perfection, and all about getting by as best one can in the environment that happens to prevail at the time.

Variations, we are told, don’t succeed because they’re “better”, but because they suit their environment. If the circumstances make it reproductively advantageous to atrophy your brain and become a sessile polyp, then that’s evolutionary success. Barnacles are jerry-built because their environment militates against over-engineered solutions. It’s quite likely that your most interesting features are spandrels. If your genome keeps you alive, it doesn’t matter that it’s increasingly piggy-backed and full of junk.

I’m not sure whether all those “me-too” fields of endeavour that have jumped on the evolution bandwagon have kept up with this later concept of what evolution is, and is not. People expect, not always correctly it is true, that Windows evolves to be better, and that marriages don’t evolve by means of uxoricide. Evolutionary design algorithms aren’t expected to come up with massively inefficient components that do just enough to get by. “Neutral drift economics” doesn’t have much traction. But one might expect that science itself would keep itself up to date on the theory. So what would a 21st century view of science, more consistent with evolutionary theory as it now exists, look like?

The first error to jettison would be the mostly unrecognised independence from environmental influence that drove the original Darwinian theory. “Progress” was so integral to nineteenth century thought that, in practice, it outweighed the selective character of the environment. The hidden idea, I guess, was that the whole biosphere was becoming better and better adapted to the environment, seen as a fixed “target”, and that is the reason one could map it to a constant scale of progress. The evolutionary truth, however, is that the environment keeps changing haphazardly, and organisms struggle to keep up with it however they can. If a species is perfectly adapted to its environment, it may the next day become perfectly non-adapted because the environment has altered. The course of evolution, like relativity, can no longer be measured on a fixed scale.

Science, though, has traditionally seen itself as following some invisible path to an ultimate objective truth (another inexplicably fixed scale in despite of the relativistic universe), quite regardless of science’s environmental setting in Western culture. This is a completely un-evolutionary view. Targets are definitionally teleological. Science can no more be separated from its transient cultural environment than organisms can be seen in isolation from their physical one – or if it can, an entirely new principle will have to be defined. The only view you get from nowhere is – nothing.

A more evolutionary approach to science would be to recognise that theories survive to the exact extent that they are well adapted to the culture in which they arise – a culture which is only influenced by science to the kind of degree that natural environments are by the species that dwell in them, ie relatively little. Most of the influence is the other way: environment moulds phenotype, not the reverse. If science truly does evolve, then it is not particularly likely to be in the direction of increasing truth (if that could ever be defined without reference to a thoroughly teleological view of success tied to social context), but in whatever direction ongoing sociological acceptability dictates.

Now such a modern view is entirely consistent with the evidence on a number of fronts. In the first place, it’s consistent with the findings of the philosophy and sociology of science over a number of decades, which have uncovered both the theory-laden nature of science and its underpinning non-scientific assumptions. But even apart from that it’s clear that science follows changes in social mores closely – in Darwin’s time and up until the Second World War, for example, views on racial inequality were widely shared in both society and science. It is no coincidence that, following the Holocaust and the Civil Rights movements, biology too now minimises the reality of race even as an entity, let alone as a marker of evolutionary progress.

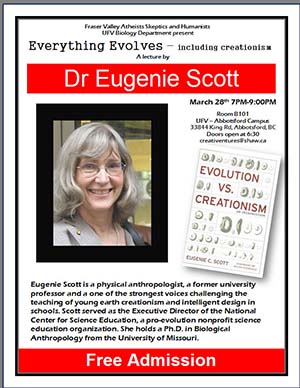

Consistent with that, one can track the fortunes of scientific traditions by the parallel fortunes of their host-cultures. In the nineteenth century German science, with its specific character and approach, led the world, especially in biology. The World Wars cut it off in its prime (and even Einstein might have disappeared into oblivion but for the efforts of Arthur Eddington, inspired by his pacifist Quakerism, to have his ideas heard despite the First War). Russian Science, again with its own character, lost influence here because of the Iron Curtain, and has fared no better than Germany’s since that fell. Loss of interest in French language and culture, in the same way, means that there are few modern equivalents to Lavoisier, Buffon, Larmarck, Cuvier, Pasteur or Curie.

Consistent with that, one can track the fortunes of scientific traditions by the parallel fortunes of their host-cultures. In the nineteenth century German science, with its specific character and approach, led the world, especially in biology. The World Wars cut it off in its prime (and even Einstein might have disappeared into oblivion but for the efforts of Arthur Eddington, inspired by his pacifist Quakerism, to have his ideas heard despite the First War). Russian Science, again with its own character, lost influence here because of the Iron Curtain, and has fared no better than Germany’s since that fell. Loss of interest in French language and culture, in the same way, means that there are few modern equivalents to Lavoisier, Buffon, Larmarck, Cuvier, Pasteur or Curie.

It seems a rather depressing picture, but if evolution is, as is claimed, a universal principle, then one ought not to make any exceptions for the science that studies it, and one ought to keep ones evolutionary model up to date. If evolution has no plan or purpose, and is solely to be judged on the fitness of its products to survive, then that must apply to everything that evolves.

Alternatively, and perhaps necessarily if science is to survive, one must abandon evolutionism and say that, by the criteria of current evolutionary theory, there are many things – including science – that do not evolve at all, but change under some entirely different principle. In fact, reviewing the long list with which I started this piece, there is very little that does truly evolve, if biological evolution be taken as the template. The trouble is that you then have to start admitting teleology – real, intelligent, teleology – into any process with which you wish to associate “progress”, since modern evolutionary theory doesn’t do progress.

That won’t happen yet, because Western liberal society, the intellectual “environment” of science, is still romantically wedded to the idea of inevitable progress. Even in biology. Some maladaptation to environment is involved there, methinks.

Hi Jon,

Darwinian evolution, and the vast generalisation (and baggage) that the term “evolution” brings with it, have been a source of endless argumentation for well over a century. It astonishes me that even today, there are people who will go to great lengths to avoid thinking that much of Darwinian thinking has undergone many changes, many of them driven not by science, but by socio-ideological views that have been given birth by Darwin’s disciples. This synthesis of inadequate science proposed by Darwinian semantics, and the underlying beliefs that motivate people to undertake such synthesis, is more interesting (as it reveals the complexities of human beliefs and outlooks) than anything Darwin has proposed (or for that matter that biologists have proposed).

An analysis of why we are faced with this state of affairs would require a great deal of effort, and I suspect the end result would be that people wish to develop a worldview that sounds scientific. In any event, my suggestion to people who are bothered by what Darwin has proposed, would be to take some time and study Philosophy of Science – it is this area that provides insights into the thinking underpinning the Sciences, and also would show why much of what is popularised as science is in fact speculation, often closer to science fiction and should not be taken by people as established (or proven) Science.

GD

It’s paradoxical, isn’t it, that whilst one denies that science has cultural biases, one is letting slip the very objectivity one values. Conversely, seeing science as a culturally conditioned human enterprise, though it denies you the “view from nowhere” actually enables you to approach closer to the best truth that humanity can attain.

PoS (sometimes hotly hated by scientists as a denier of their objectivity, and therefore “nonsense”), as you rightly say, has done a good job of pointing out these principles. The next step is the historical one of seeing exactly which hidden ruling biases exist, investigating where they came from and discovering, thereby, what alternatives are possible.

After that you get to choose – and I suppose, depending on your character and your insecurities, you’ll still assume that your own native culture is best, or let some other consideration push you aside from the mainstream into the uncomfortable borderlands. Most people, in all walks of life, live by the dictum “It is better to be average than right.”

Philosophy of science is does a good thing in trying to figure out what it is that science is actually doing and how. “Science studies” on the hand, when I have troubled to look at them, seems to be a case of the subjective pot calling the subjective kettle black. It’s a self defeating position, which should be obvious. When it’s all done, all they have “discovered” is that scientists are human, when it would have been more useful for them to discover that about themselves. It all seems like saying “you’re biased!” and hoping that no one will notice that they are too. Some people are bothered by the prestige that science has in our culture, mostly because they think that, whatever their department is, it should be the one with the prestige. Let the sociologists cure cancer if they want some respect. 🙂

pngarrison

Seems to me the danger with sociologists of the post-modern persuasion is less to pit their objectivity against others’ subjectivity, but to deny any possibility of knowledge at all, and to rejoice in it by lapsing into incoherence (witness Derrida, etc).

The challenge, in my view, is to use the truth of the fallible human basis of knowledge as a stimulus to humility and openness to new truth (and conversely counter arrogance). I’d even say that there’s a theological dimension involved in retreating from “the triumph of human reason” and returning to the realisation that only in God is genuine truth to be found – but that’s for post-post-modernism to discover.

But I’m not sure I want to go where your last remark is heading – there are already too many crass cartoons about science finding cures for cancer and religion failing to do so – it doesn’t seem productive to start throwing sociology on the scientistic scrap-heap too, as logically the arts, the humanities, politics and everything else will soon join the “they’ve provided no cure for cancer” pile. Hydrologists and astronomers aren’t famous for their medical breakthroughs either.

To my mind there’s a role in society for those sociologists who have sought to document the societal costs of finding cancer cures, whether that’s investigating Sigmund Rascher’s human experimentation in Nazi Germany or the same dehumanising phenomenon in the “free world”.

At the same time it’s interesting how that feeds into one of the points made in the OP: much valuable work on cancer was done, and forgotten after 1945, in Nazi Germany.

It is the complexities of human beliefs and outlooks (we often refer to these as subjective outlooks) and the arrogance of some scientists (often those who have not found a cure for anything, and self proclaim they and science will eventually cure all ills) that leads to arguments and exaggerated claims. I am not aware of anyone who has found a cure for cancer, and Darwinians would, I suggest, be last in the line in finding such a cure. On prestige, many years ago, some results of my research were used by other groups as part of their effort in seeking a “cure” for cancer. I did not sense any prestige in this, but I did notice a sudden increase in various (until then unheard) groups seeming to claim they had been doing the research I had published, and were now publishing theirs – me thinks they smelt funding opportunities. This is an example of being mealy human. My research results did not bring a cure for cancer, nor has anyone individual. Usually good and useful science is the result of effort by many groups in many disciplines – PoS is valuable in enabling scientists to understand the basis (or basic thinking and assumptions) made by other scientists working in very different and highly specialised areas. When we move outside the Physical Sciences (and some of the more specialised Bio-sciences), areas such as Sociology may enable us to incorporate cultural and historic outlooks on areas relevant to application of the Physical Sciences.

It is this approach that would enable scientists to put our views in context, and also perhaps find some humility when assessing our efforts in terms of serving humanity and this planet, instead of claiming to be the source of all goodness and Truth. Too often we are really stupid when it comes to understanding ourselves and our community, and may end up seeing more harm then good as we assume any outcome from Science must, by definition, be good and true – such an outlook is self-deception.

The reality is that quite a lot of progress has been made in cancer therapy, and even more in understanding the specific pathways that are disabled by mutation or epimutation in the onset of neoplasia. We’ve moved from the days of no effective therapy beyond surgery and radiation to therapies based on selective chemical toxicity for growing cells, to therapies based on targeting specific oncogenes. The old dream of inducing the immune system to attack the cancer is finally seeing some success. No one who studies cancer has ever really thought there was going to be one magic bullet for all cancer, although a lot of the public can’t seem to understand that.

Jon, pngarrison:

It seems to me that sociology (like social science generally) has gone through two phases. In the earlier phase, it sought to legitimate itself by aping the natural sciences. So you saw a superficial use of mathematics (lots of American college students running surveys on the sex life of other American college students, and then crunching the data using statistical methods — learned not from the math department but from a special course in the sociology department on “statistics for social scientists who aren’t too good at math”), and you saw lots of Latinate jargon, to give the vocabulary of social scientists a quasi-physics or quasi-biology feel; and of course sociologists thought that their cold “objectivity” set them apart from those mushy people in the humanities who talked about “subjective” things like love and justice.

Modern sociology, on the other hand, has been more and more influenced by “deconstructionism” and by other variations on the radical relativism of knowledge, which seems to have started out in certain German philosophical circles, then, via French literary-critical circles, to have penetrated the whole “Arts” side of the academy, social sciences and humanities alike. So the new thing is not to try to be as objective as the natural scientists, but to show that the natural scientists are just as subjective as oneself. Thus, natural science is declared to be a culture-bound activity, governed by the prejudices of “dead white males,” and horribly Western-centric, or human-centric (not caring enough about trees and rocks), etc. In this view, the “laws of nature” have nothing to do with nature, but are human creations, projections of human will and imagination upon nature, and therefore don’t teach us anything about what is really out there.

So when I think of sociology, I think of jumping from the frying pan into the fire. The earlier sociologists wanted to reduce the truth of very important human things to the cold truths of the natural sciences, which deformed the human things by interpreting everything that was high (e.g., love, justice) in terms of things that were low (e.g., sex drive, the imposition of one’s class interest upon society); the current sociologists are willing to give up any idea of truth at all. Not much of a choice there!

There was, for a short time, a healthier kind of sociology, a humanistic sociology, which did not try to ape the natural sciences by loading itself up with jargon and mathematics: Peter Berger, Jacques Ellul, etc. They were joined by other social scientists, such as economist E.F. Schumacher and psychologist Erich Fromm. Those social scientists you could actually read, because they wrote (mostly) in good, jargon-minimal literary style, and their writings actually made you a better human being, because they talked about social matters as human beings, not as cold, objective scientists gazing down at human beings as lab rats; and most important of all, they believed that there was such a thing as truth. But nobody does social science that way anymore. You couldn’t get a Ph.D. or tenure doing that kind of humanistic sociology. You either belong to the old guard which still wants to be “rigorous” and “scientific” — meaning reductionist and anti-human — or you belong to the new group which emphasizes the impossibility of obtaining any truth, and hence spends its time mocking the truth-claims of other disciplines — and other sociologists (except for the sociologist writing the book or essay, of course).

As for the point about natural science being more useful than sociology, I agree that this is usually the case, but it is a dangerous point to use in argument. If taken to its logical conclusion, it would mean removing all public funding from the “Arts” subjects (except Economics), and drastically reducing funding for all “science” subjects which could not prove their immediate or at least potential usefulness to medicine, manufacturing, etc. For it is no more important to the American economy to discover how many extrasolar planets there are or whether a multiverse exists or whether the Cambrian Explosion lasted 5 million or 50 million years than it is to produce a masterful interpretation of King Lear or to decipher historically information-rich ancient Tocharian texts. I hold to the older idea of the university as the place of theoretical thinking, and I think all disciplined theoretical thinking should be subsidized and protected by the university, whether in the natural sciences, social sciences, or humanities.

My problem with many of the social sciences is not that they fail to cure cancer or create more energy-efficient automobilies; my problem is that I think they house a good deal of undisciplined theoretical thinking, and I strongly suspect that there is a direct connection between the lack of discipline in the thinking with the passion-driven social/political agendas of the social scientists themselves. When you really want something to happen — whether that is abortion on demand or affirmative action programs or socialism or the blocking of an oil pipeline that is being protested by native Americans or the strict control of American (but not Chinese or Indian) CO2 emissions or the granting of legal rights to animals or whatever — there is always the very strong temptation to loosen up on the scholarly standards of both research and argument, if you think that will persuade others to support your desired social goals. I think that all university departments have become much more politicized than they used to be (even natural science departments: there was a lovely article not long ago by a climatologist who notes how much more politicized climatology conferences are now than 30 years ago), but I think that social science departments are more prone to succumb to politicization than others, because the majority of professors who go into social science in the first place — especially Sociology and Women’s Studies and all other “X Studies” (where X is the special interest group that is the current cause celebre) — have strong leanings regarding the way society should go and very much see the university primarily as an engine of social change.

Funny you should say this, Eddie – relevant post in preparation.

I can’t resist telling a story to illustrate the strength of the politically correct positions around a University. Years ago I joined a friend for a dinner party with some Univ of Texas at Austin faculty. I only knew the hostess, my friend, so I probably should have mostly observed, but I ventured a joke that I thought was so silly it would be recognized as a joke. I suggested that the controversy about what to call a committee chairperson should be resolved by calling them the chairentity, since they probably have committees in Hell, and we wouldn’t want to offend the devils by assuming that they are male or female. Incredibly, there was a guy who took me seriously. He wanted to discuss my proposal. I was so stunned that I don’t remember how the ensuing discussion went.

A typical case of language oppressing minorities, in this case damned minorities. As I was reading somewhere today, the whole Postmodern thing was a fad that was born and quickly expired in France in the 60s, but has ruined two generations of students in all disciplines in the west since. For some reason, theology’s suffered more than most – making your anecdote more than likely.

The brief time I spent doing social science (and that only psychology) preceded all that – in my day the controlling “objective scientific paradigm” was the New Left. One of my lecturers quite seriously divided history into pre- and post-Woodstock.